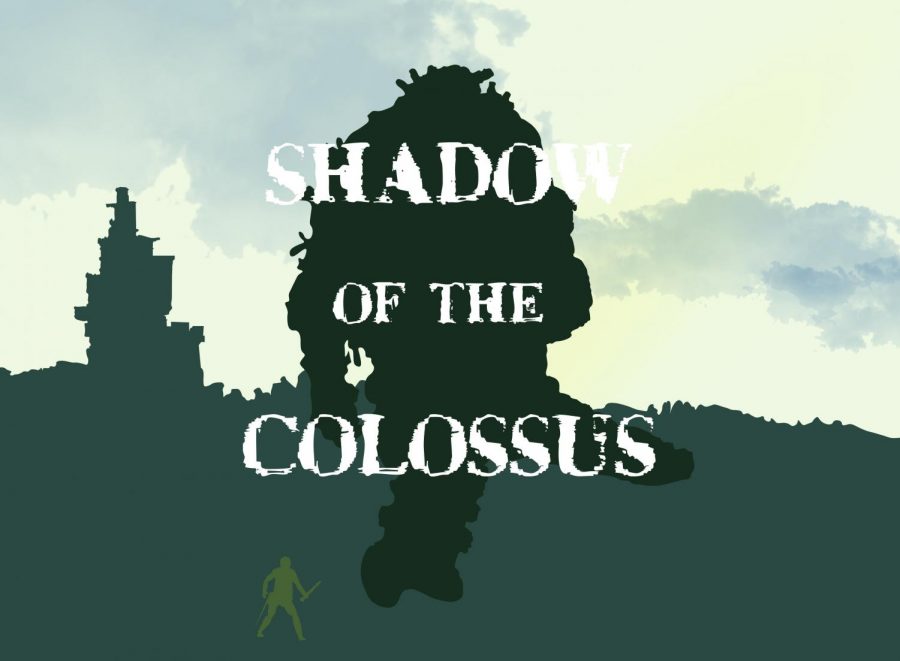

Shadow of the Colossus

Columnist reviews video games; this week focused on older game on PlayStation

This game was originally released for the Playstation 2, but was remade to work with newer consoles.

March 4, 2021

What is it that makes a compelling experience in a video game? Developments in both technology and design allow games to become vast, immersive works of interactive art. In this column, I’ll explore why I find games to be such a powerful medium for expression by reviewing old and new games.

“She was sacrificed for she has a cursed fate. Please, I need you to bring back her soul … ”

“That maiden’s soul? Souls that are once lost cannot be reclaimed … Is that not the law of mortals?”

I remember the first time I played Shadow of the Colossus. It was on some kind of Sony holiday demo disk of upcoming games sent out promotionally, excavated from a cereal box in the days when companies would sometimes put CDs in there (yes, I’m old).

I remember starting this game up and being greeted by an intensely atmospheric 15-minute long opening cutscene that could come straight out of some esoteric art film and wondering what exactly this thing was. I had never seen anything like it, and as of today, I’m not sure I have again.

That’s really what separates Shadow from other games, especially its contemporary titles: the use of atmosphere. Despite the lengthy intro cutscene, there’s almost no dialogue.

In fact, once you’re given your mission by the only other living, speaking character you will ever encounter, you’re released out into the Forbidden Lands to slay sixteen towering beasts known as Colossi with no other companion but an amazingly trusty horse.

The story is told almost exclusively through action and setting. Other games have attempted this style of context-based narration, but I don’t believe any other has ever been as successful.

Before you set out, you are told a basic motivation for your character, an unnamed young man known in the fan community as “The Wanderer.”

He defied a major cultural rule for his people in coming to this place, with the intent to bring his love back from the dead by any means necessary. The means available turn out to be some kind of disembodied, multi-voiced deity that speaks through the temple ceiling and may or may not be capable of actually raising anyone from the dead.

If this confuses you, that’s kind of the point, as a huge part of this game’s narrative design is focused on player interpretation. It will give you all the information necessary to understand what’s happening, but you have to do the work.

The landscape of the game itself is a big part of the experience. It’s desolate and strangely empty for an open-world game. Spend enough time roaming the vast hills and forests listening to nothing but the wind almost literally whispering in your ears and you may even begin to feel that it’s lonely here.

Scale is a huge theme of the game, in the design of the Colossi (the only enemies you’ll find), in the architecture of the grand bridges and temples that dot the landscape, in the incredible orchestral music score that follows you into battle.

There is a profound feeling of desperation you begin to feel as you lead The Wanderer to accomplish the insane task of physically climbing a multi-story beast to slay it with only a sword, all in a perhaps futile effort to get back his dead love.

Is it perfect? Heck no. Its weird physics engine is a notorious headache to deal with. But no other game has spent as much time occupying my thoughts after playing it like this one. I still notice new details every time I replay it. It is a masterclass in subtle design.

Rating: Sixteen colossi out of 10.