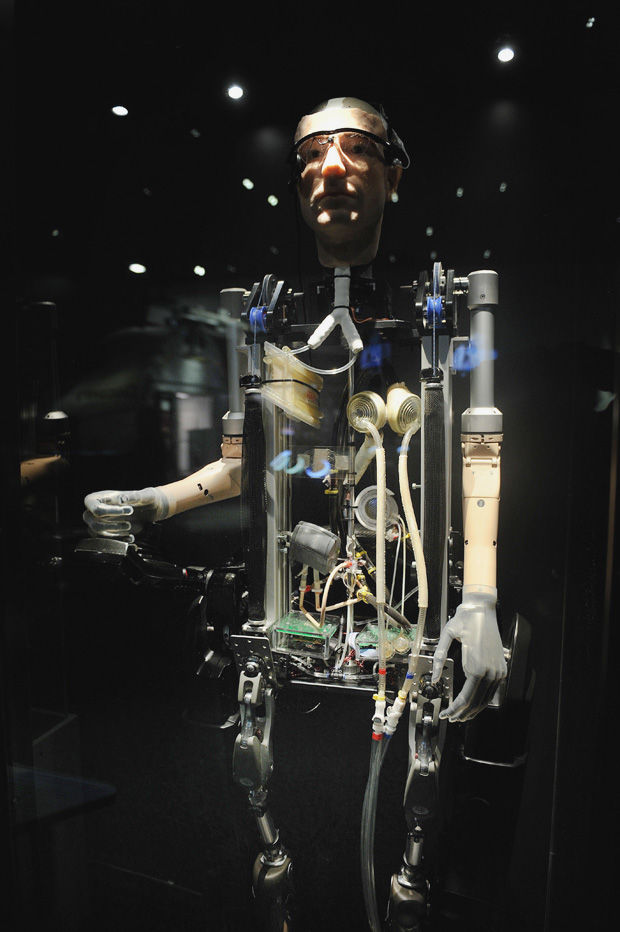

Artificial Humanity

The first-ever walking, talking bionic man stands on display at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., Friday, October 18, 2013. The model is a 6-foot-tall robot built entirely from bionic body parts and implantable synthetic organs. (Olivier Douliery/Abaca Press/MCT)

April 23, 2015

Siri and Cortana may be joined in the future by much more intelligent companions.

Interdisciplinary graduate student Antonia Bodley defended her dissertation, called “The Android and our Cyber Selves,” Tuesday afternoon in the Foley Speaker’s Room in Bryan Hall.

Bodley discussed android theory, her research on androids and artificial intelligence (A.I.) in fiction and reality, to better understand our own humanity and the potential role of androids in the future.

“I’m what you’d call a skeptical optimist,” Bodley said, when asked what the world may look like in 200 years. “Not everything we see in pop-culture is something to look forward to, but an openness to the future is important.”

By combining studies of philosophy, American studies and English with her love for science fiction, Bodley has spent the last five years combing through films, trying to understand how far from fiction reality will prove to be.

“By reflecting on androids with minds like us and bodies like us, we can try to define ‘like us,’” Bodley said.

One of the longest-running interdisciplinary degree programs in the country, WSU’s Individual Interdisciplinary Degree Program helps students tackle issues from multiple directions, said Lisa Gloss, Academic Coordinator for the Graduate School.

“Many of the complex problems we face can’t be solved with just one discipline,” Gloss said.

Graduates from the IIDP have little trouble securing faculty and government positions thanks to their broad education, Gloss said.

Bodley’s research comes in three parts: Mind, which includes embodied and disembodied artificial intelligence; body, or human-robot interaction like cybernetic prosthetics, and society, covering the non-human dilemma and ethics of post-human relationships.

She described post-humanism as an exploration of natural boundaries of mind and self. Some, she said, argue we already live in a post-human world, with drugs and prosthetics that alter the natural course of our bodies.

Warner’s law states that technology grows at an exponential rate, and Bodley said modern tech like Honda’s Asimo robot and hyper-realistic silicon dolls made in Japan have paved the way for a future accompanied by androids with A.I. capable of thought and emotion.

Human interactions with robots and androids will raise ethical and moral controversy, and will challenge concepts of self on a societal scale, Bodley said.

“If we can construct any A.I., why not create robots who want to be slaves?” asked Eugene Apperson, one of Bodley’s dissertation defense committee members, bringing to the table one of the ethical issues behind Android Theory.

Bodley said by creating A.I. to be used in a presumably mass-produced group of robots or androids, a new race would essentially be created, raising questions regarding their rights as sentient, but artificial, beings.

Bodley’s interest is rooted in a specific scene of Star Trek, wherein the Enterprise’ android, Data, is asked to sacrifice his ‘life’ for research purposes. This raised questions of Data’s rights as an android, which Bodley describes as a humanoid meant to imitate humans as closely as possible.

“We don’t even know how our own minds work,” she said. “We should take the next step carefully.”