Taking a chance on Land of 10,000 Lakes

Columnist dives into unknown to try her hand at wilderness life

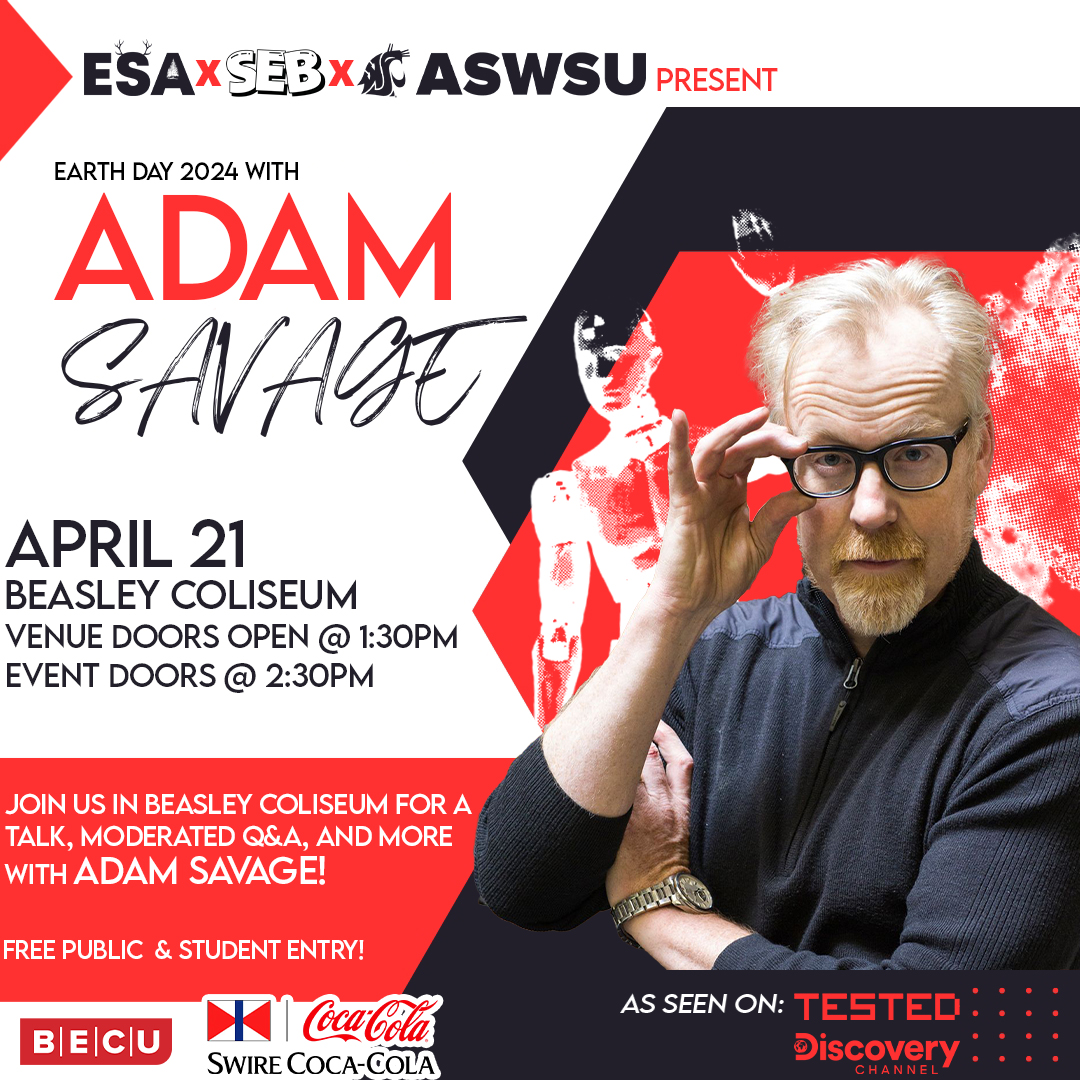

Portia Simmons at Boundary Waters checking on students on a course with their boss.

September 16, 2021

During quarantine, I had the desire to walk into the woods and limit contact with the modern world for a few months. No news, no cell phone – just me, my tent and the encompassing wilderness.

In order to make this fantasy a reality, I decided to apply to an outdoor school. In the past, I have worked as a camp counselor, but I had never been backpacking.

Even though I had no experience in the realm of nomadic traveling through the woods, I was hired at the Voyageur Outward Bound School. I accepted my job as an intern and was soon on a plane to Minnesota for the summer.

When I arrived, I had no idea what I was doing. Although there was an underlying current of uncertainty in my outdoor skills, I was extremely excited to be there. I was accepted and welcomed into the community with open arms.

I plunged right into the deep end of learning new outdoor skills, such as rock climbing, white water rafting, backpacking basics and how to carry a canoe on my shoulders (portaging). As the weeks went on, not only did I gain wilderness knowledge, but I started to gain confidence about my abilities and myself.

As interns, we had one of the hardest jobs. At a moment’s notice, we could be sent out into the Boundary Waters, armed with a map, compass, gear and canoe to go on an adventure. This includes retrieving backpacks that students had left, returning a student to the field that had left due to medical reasons (revac), or driving to Duluth to drop a student off at the airport.

Planned days had us on Homeplace Base, doing tasks like assisting in the dog yard – we had 60 dogs for our winter course — assisting the ropes course, performing maintenance or assisting groups of students transition from their wilderness adventure back to Homeplace.

I was allowed to fail and learn from my mistakes without judgment. I was supported by my co-workers and, eventually, my friends. Although I was building faith in myself, my reasoning for why I was there would sometimes waver.

The reason I was hired, as told by my boss later on during my exit interview, was because of my spirit. I displayed the skills you couldn’t show by tying a trucker’s hitch or setting up a tent. I was told that I have a go-get-them attitude and the ability to jump into any situation.

No matter the challenge, I was up for it. And, boy, was I challenged. I was physically, mentally and emotionally pushed. The experience tested my body, mind and soul, but I would do it all over again in a heartbeat. I achieved a mastery you cannot put on a resume: the ability to believe in myself.

As the summer came to a close, I was extremely torn. I did not want to leave the world that had taught me so much about myself in such a short amount of time.

I can tell you about the great memories, such as the lake swims, the nature hikes, the all-day paddles and the wise conversations I had with others, but I cannot truly explain the profound metamorphosis I underwent.

This article is only about 500 words, so I honestly cannot describe the whole experience I had in Minnesota and what it felt like to be there. The intention for sharing my story about my summer in Minnesota is to tell you, the reader, that nothing is standing in your way. If you want to do something, do it.

I believe things happen for a reason and that anyone can do anything; all they have to have is faith in themselves. Take it from me, the novice woodsperson that now owns a broken-in pair of hiking boots, which are sitting by my door and waiting for my next adventure.