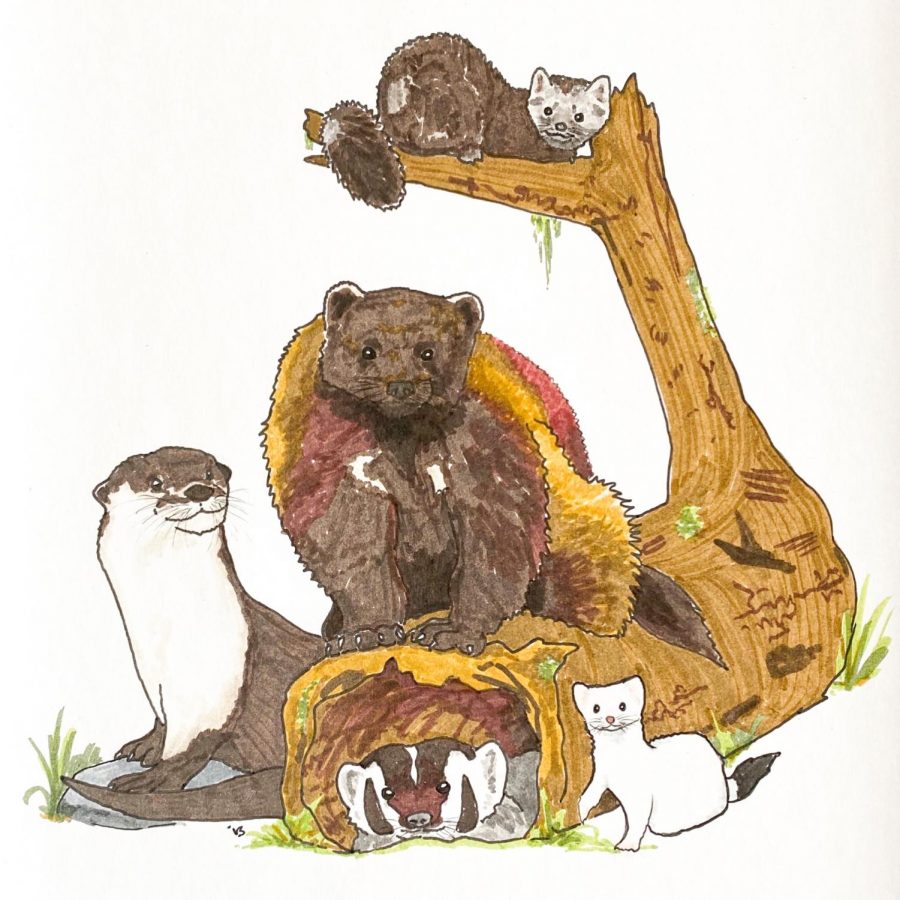

Marvelous Mustelids

Many species like weasels, river otters belong to family Mustelidae, live right here in Pullman

Left: River otter. Center: Wolverine. Bottom: American badger. Right: Ermine. Top: Pine marten.

September 15, 2021

When you see a weasel slink down a burrow, a badger trot off across the prairie, or an otter dive back under the waves, you might not realize they all have something in common. They are all mustelids.

Mustelidae is the largest family in order Carnivora. All mustelid species share a few key characteristics: a long body, stout legs, stubby snout and prominent anal scent glands. Think skunks; they use their scent glands for defense. Skunks used to be classified as mustelids, but recent genetic analysis placed them in a family of their own, Mephitidae. Most mustelids use their glands primarily for territory marking.

Weasels are perhaps the most secretive mustelids. There are several seldom-seen species native to eastern Washington, including the short-tailed weasel, or ermine, and the long-tailed weasel. Weasels are ferocious predators that prey on small vertebrates.

Stoats prefer rabbits and have no problem tackling a bunny up to five times their size. Each fall, these species ditch their drab summer fur for a breathtakingly snow-white winter coat. Minks, weasels’ similar-looking semiaquatic cousins, do not display such seasonal dimorphism.

River otters are closely related to weasels. Their dens have submerged entrances because they are truly at home in the water. Webbed feet and powerful tails propel them to depths of up to 60 feet, and they can hold their breath for 8 minutes.

Long, sensitive whiskers enable otters to hunt crayfish, frogs and fast-moving fish. Otters are highly intelligent; they engage in play, carving out shallow slides in riverbanks and snowbanks and slipping down them headfirst to their heart’s content.

On the other evolutionary side of the weasels are the martens. Pine martens are phenomenal climbers capable of scaling towering pines, as their name implies. In the same group as martens are wolverines, the fiercest predators in western North America. Despite weighing an average of only 40 lbs., wolverines hunt adult elk. Wolverines also scavenge, fighting wolves and even bears for their kills.

Badgers are the most distinctive mustelids, thanks to the bold striping on their faces. Grasslands with sandy soil are a must for badgers since they mainly prey on small burrowing mammals like prairie dogs. Strong forelimbs tipped with long claws allow them to unearth prey and excavate burrows. Badgers’ burrows, called setts, often consist of many interconnected tunnels and chambers. During the summer, when they roam the most, some badgers may dig a new burrow to sleep in each day.

Most intriguingly, badgers have been known to associate with coyotes during hunts. If a prairie dog escapes the badger, the coyote catches it, and vice versa. Both species experience higher hunting success rates when hunting together. Beyond this mutualistic hunting behavior, remote camera trap footage has also captured badgers and coyotes playing with each other.

Mustelids live in water, on land and even in trees. They are excellent climbers, swimmers and diggers. They are also highly intelligent and engage in play behaviors, sometimes with other species. This diverse family of furry predators is determined, crafty and persistent. Keep an eye out for their fluffy forms, wherever you travel next.