Sexual assault exam kits backlogged statewide

DNA from Kits become part of a larger database of suspects and can be used to track repeat offenders

MICHAEL LINDER | The Daily Evergreen

Aspen Durand, senior wildlife ecology student and a leader of “Help the WSU Bears,” listens to design concepts for a new WSU Bear Center on Friday.

October 23, 2017

Seven small boxes sit in storage at the Pullman Police Department. Each of the boxes contains evidence from a sexual forensic examination kit collected at the hospital when seven people came in and reported they had been sexually assaulted.

These boxes are several of thousands of kits across the state that remain untested.

The state attorney general’s office recently received a $3 million grant from the Department of Justice to help test those kits and implement training for law enforcement. Part of the grant will also be utilized to create a team of investigators to travel across the state collecting formal data on the number of untested kits so they can help police departments prioritize and test the backlogged kits, each of which costs about $680 to test.

The bulk of the backlogged kits are housed in the more populous areas of the state, but the frequency with which college towns like Pullman see sexual assault has created a network of organizations that recognize the importance of the issue, said Catherine Wilkins, a trained Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner nurse at Pullman Regional Hospital.

“It’s profound, and we, being in such a teeny tiny community, we have people coming in nearly every weekend, and that’s considering 90 percent are not coming in,” Wilkins said. “It’s a lot and it’s a big deal.”

While police departments across the state have struggled under a large backlog of kits, Pullman Police Chief Gary Jenkins said they have not had a problem testing the kits that need to be tested when a survivor wants to move forward with a case. They currently have seven untested sexual assault examination kits, and the alleged perpetrator is known in all cases.

In five of the cases, the survivors did not want to move forward with their case. For the remaining two cases, it was found that the issue lay in whether or not consent was given, so the evidence was not in question. Jenkins said the kits are retained based on the severity of the assault. Assaults that are committed through force or use of a weapon are kept indefinitely because there is no statute of limitations. For lower-level sexual assaults, kits are kept for 10 years.

“Any of the sexual assault kits that have needed to be tested, have always been tested,” Jenkins said. “There is no reason to test the kit if the victim does not want to press charges.”

He said the untested kits can help build on the DNA database created by the Washington State Patrol to help identify repeat offenders.

According to a study on repeated rape among undetected rapists, of the 1,882 men in the sample, just over 6 percent met the criteria for rape or attempted rape. Of the 120 men that comprised the six percent, 76 — or 63 percent — reported committing repeat rapes.

In one of the cases Wilkins saw, a woman came in and originally did not want to have her kit tested, but later changed her mind. Her kit was linked to another kit containing evidence from the same perpetrator. She said that is an example of the positive benefits to undergoing an exam and getting the kit tested.

“Collecting that evidence and having it stored can never hurt their case, it can only help,” Wilkins said. “Even after the initial few days, five days, they don’t want to report, it’s still helpful to get the evidence and they can always change their mind.”

The process of collecting evidence for the kit begins when a patient comes into the hospital and reports a sexual assault. At that point, if a SANE nurse is working, they will handle the entire process. If a SANE nurse is not available, all emergency room nurses know the protocol and policy and can perform the exam.

An advocate from Alternatives to Violence of the Palouse is also called immediately so that the survivor has access to resources through them. If the survivor does not want the advocate there, they can ask them to leave. But they are always called, Wilkins said, so the survivor does not feel like they are bothering anyone by requesting an advocate.

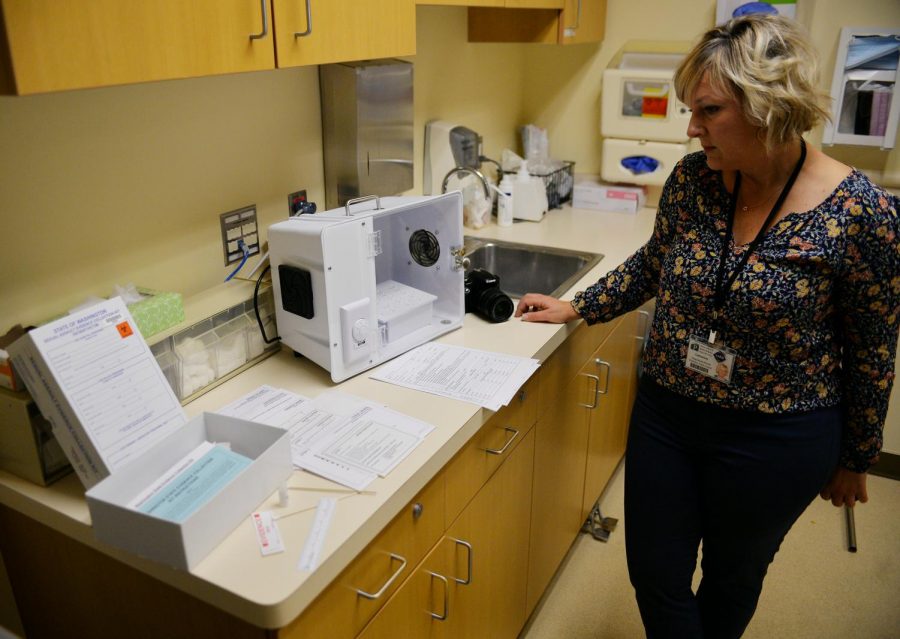

After a medical exam is performed if necessary, the patient is asked to walk the nurse through the history of what happened in as much detail as the survivor would like to provide. Then the nurse goes through the sexual assault examination kit piece by piece.

Each step has a numbered card with instructions for how to properly obtain the evidence. The patient is asked to remove their clothing while standing over tissue paper to collect trace debris before swabs are collected from the skin, fingertips, vagina and rectum (depending on where the survivor states that contact occurred). Blood and urine may also be collected. The evidence is then returned to the kit and kept within the nurse’s sight at all times until the police arrive to retrieve it.

Within five days, evidence collection is part of the process. After that, the assault can still be reported, but evidence collection may not be a part of it.

At any point throughout the examination, which generally takes two or three hours, the patient can refuse any part of the process.

“If at any point they say no, we stop,” Wilkins said. “They are in control through the whole process.”

Wilkins, who has worked at Pullman Regional Hospital for 10 years, said she hopes that a greater knowledge of the process and the availability of specially trained nurses will encourage more people to come forward and report.

Each of the kits collected by nurses at Pullman Regional Hospital is given to the police with jurisdiction over the area where the assault occurred. From there, it may be used during a trial or investigation, or it may end up joining the thousands of other untested kits from across the state, as long as the statute of limitations lasts.