Colored locks and corkscrew curls

February 17, 2017

{{tncms-asset app=”editorial” id=”234cc896-f4c7-11e6-9963-e7d28bc44632″}}

Tight, black corkscrew curls and volume times two – this is just one type of African-root hairstyle. There are locks, cornrows and even twisted or braided weaves, all in any color.

In honor of Black History Month, I wanted to learn about the history of African-root hairstyles and what it means to African women.

Although we see ourselves as a culturally and ethnically diverse nation, we still have backward views of fashion standards in the unprofessional world. Amber Moreland, vice president of the WSU Young Women’s Christian Association and member of the WSU Black Student Union, gives some insight on the history of formally known “dreadlocks” and how these locks are currently viewed.

“We say locks because – fun fact on history, the word ‘dreadlocks’ came from back in the day by people who used to say that the style was dreadful,” Moreland said. “So people would call them dreadful locks which was shortened to dreadlocks. Now, a lot of times, black people will call them locks to eliminate that stigma of them being ugly.”

I also spoke with Terlona Knife, who identifies as a Zimbabwe-British woman and wears blue and gray crochet faux locks. Knife is a member of the Black Student Union and the historian of the Queer People of Color and Allies.

Knife explained that although some people do have genuine compliments for her hair, this does not mean her hair is generally accepted. Locks are seen as exotic and out-of-the-ordinary, as if they are an object people can touch. Due to this, Knife and Moreland have found themselves violated by people trying to touch their hair.

“Respect that I don’t want another person to be touching me, and you don’t know me, and that we’re not friends. I don’t owe you,” Knife said. “They are like, I should have the privilege to touch your hair. My hair. Key word: my.”

We should respect women’s hair because it is how they choose to express themselves, and hairstyling often requires a lot of time and effort. I have had a similar experience of people reaching out to feel my hair as they complimented it because it is curly. In those moments, I feel like people cross a line, because I chose to style my hair this way and I would rather someone not mess with it.

“I think black hair is important to people, especially black women. It’s like an extension of ourselves and our personalities,” Moreland said. “I think that sometimes people want to put their hands in it or talk about it, that it’s almost like it’s a violation of our personal space, our personal boundary and how we choose to express ourselves.”

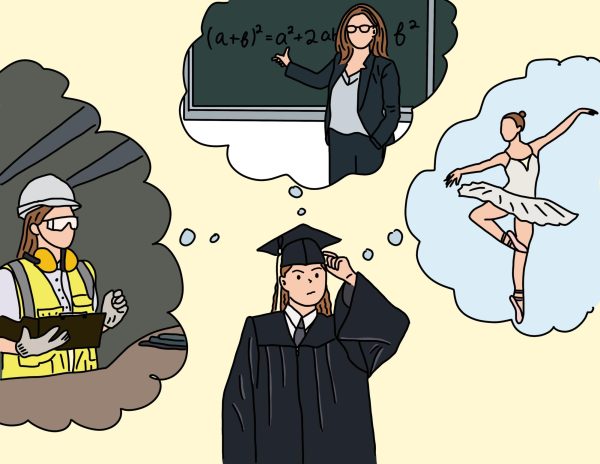

I asked Knife and Moreland how they dealt with owning their hair when people openly do not accept it. They explained it as a journey of loving yourself.

“You’re going to be on a journey of loving your hair every single day, because I didn’t just pop out the womb loving these curls,” Knife said. “I wish I did, but I did not.”

Moreland points out that whatever style an African woman chooses, if she has the confidence to wear it, she can own it.

“If it’s beautiful to her, she can rock it and has the confidence to do so,” Moreland said.

What I learned from Knife and Moreland was that African hair is a part of them. It represents their past ancestors, and it gives them confidence even when society or individuals go against it.

“Difference is important and that curly, kinky, wavy it is good. I love my curly hair so much,” Knife said. “It is sometimes a burden, it is sometimes hard to have it, but knowing that the people before you had this kind of hair. It makes you a part of something. I think it’s beautiful.”

I asked Knife what she would like to say to women who feel insecure about their African hair, and she said she believes that our sense of white hairstyles as the standard is failing girls of color.

“Diversity is beautiful. It’s a beautiful thing to not look exactly like someone else. But, I would also say that our media and standards for what is beautiful has failed you,” Knife said. “You shouldn’t be feeling like whatever you are bringing to the table isn’t good enough, because beauty shouldn’t be monolithic.”