What is conventional beauty?

European beauty standards seep into our minds, affect self-esteem of plus size women, women of color

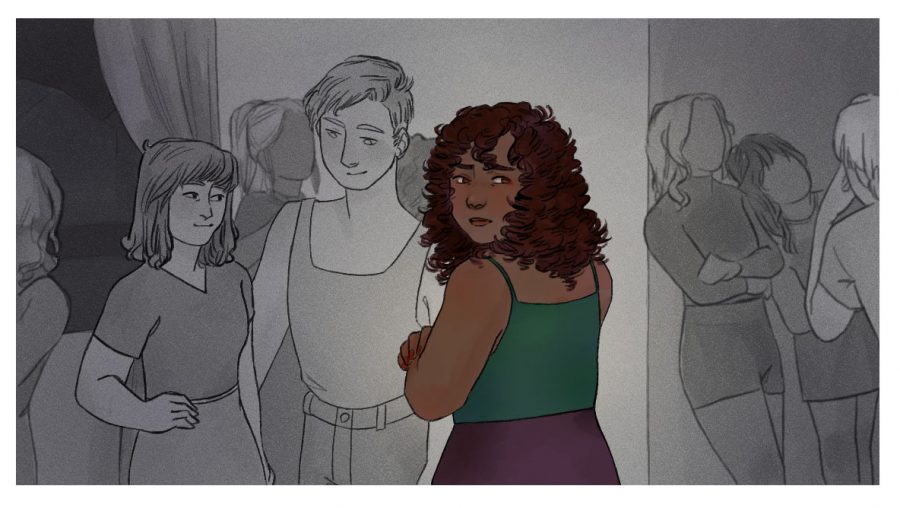

MARTHA JAENICKE | DAILY EVERGREEN ILLUSTRATION

This writer said coming to college made her more aware of the harmful effects American beauty standards, and how they breed self-hatred.

August 28, 2019

*In Your Words is a new series highlighting students’ personal stories. You can submit your piece to [email protected] with the subject line “In Your Words.”

Sylly week, also known as syllabus week, is the first week of each semester and it’s essentially a week-long party.

During my freshman year of college, my friends and I decided to join the festivities, and the word was that all the lit parties were on Greek Row.

Still new and unfamiliar to this campus, my two girlfriends and I decided to take a cab to a frat house. When we arrived, my first reaction was, “I’m way too sober to be around this many people.”

My friends could see my hesitation, but I wanted to make a good impression. I wanted to be the girl that everyone wanted.

When I walked through the frat house to get to the backyard, it seemed as though all I could feel were their eyes on me.

I had never felt so obviously black and plus size in my entire life.

Secure with my own identity, I brushed it off and tried to focus on having a good time. After a few drinks with my friends, I started to loosen up and felt more comfortable mingling.

But every time I tried to talk or dance with a guy, I felt a cold shoulder of rejection. I looked around for my two friends and saw that they were dancing with the cute guys who didn’t see me.

It’s probably important to mention that the two friends I came with were a tall blonde and a petite brunette, both of fair complexion.

I remember this moment distinctively because it was a poignant example of conventional beauty standards and how black self-hatred comes into play.

The night at the frat party wasn’t the first occasion where I’ve felt overlooked due to my race.

However, it was the first time I consciously started to pay attention to conventional beauty standards. At first glance, it often seems as though most men in the U.S. are more receptive to fair skin, medium to long hair, and slim physiques.

I don’t particularly fit into this mold, and for the longest time, I assumed this was a first-world problem that I alone faced.

I couldn’t be any more wrong. Since becoming accustomed to the campus, I have met more and more women from various backgrounds I personally found attractive but wouldn’t fit the conventional standards we often refer to.

This frustration of feeling marginalized is not just something I have experienced and tried to put into words.

There is quite a bit of research and academic thinking about the topic of beauty standards and how they affect the mental health and self-image of black women.

In an article published by the Columbia University School of Social Work titled, “The Beauty Ideal: The Effects of European Standards of Beauty on Black Women” by Susan L. Bryant, the author explores the black woman’s internalization of European beauty standards, the media and society. She describes how society’s ideas have become a part of black women’s self-perceptions.

In one particularly powerful anecdote, Bryant talks about Kenneth and Mamie Clark.

The Clarks were the publishers of one of the earliest studies about skin color and self-perception. This study from 1947 was famously known as the “Doll Test.”

The study was conducted by taking black children ages 3 to 7 and showing them two dolls — one black and one white. Then, the researchers asked the children which doll they liked more.

In the study, two-thirds of the black children chose the white doll.

This study showed how young black children were negatively affected by European standards of beauty at such an early age.

These standards tell us that lighter skin, straight hair, a thin nose, thin lips, and light-colored eyes are beautiful.

If you think this data is old and from a time when racial inequities were more widespread, know the “Doll Test” study was recreated in 2005.

This time, the conclusion remained the same. The detrimental effects deeply ingrained standards of beauty have still persist today, and while it’s been 14 years since the most recently published study, young black women are still deemed unattractive by societal standards and it’s damaging our self-esteem.

I’m all too familiar with being seen for my blackness first before my real beauty. It happens all the time.

I’ve had male friends tell me, directly, how they never really noticed how beautiful I am until they got to know me further.

Every time I hear this, I am taken aback. This is not a compliment.

I’m writing about this because I want to continue this conversation and if you made it this far, thank you. Now learn and spread the woke message that black is beautiful.

Julie Jensen • Aug 29, 2019 at 5:33 am

What a shame we place so much emphasis on looking a certain way. I’m older and don’t really care anymore but I remember. Try being a 6’2 tall woman with size 13 feet. My youth was fraught with horrible comments about things I had no control over, but karma is real. I’m in contact with many friends from my youth and karma has visited a few of my tormentors.

Really, the boys who only want you for your looks aren’t worth your time. Keep being you. It’ll all work out.

Thanks for penning this thoughtful article.