Coffee grounds could create a stronger type of plastic

Discovery could lead to customizable shin guard for athletes

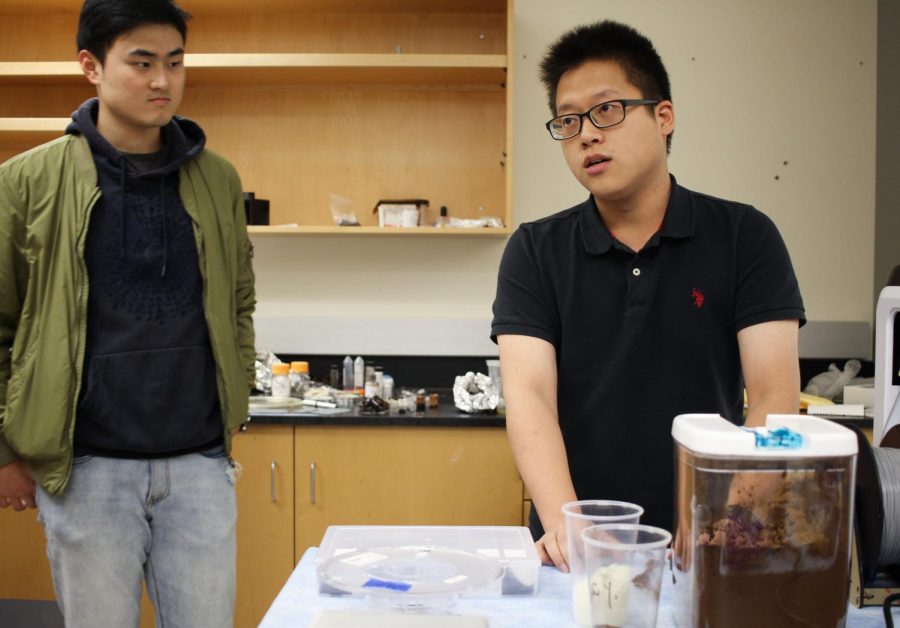

Ph.D. candidates Yu-Chung Chang, right, and Cheng Hao discuss their research towards using coffee grounds to create plastic on Thursday afternoon in the Engineering Teaching Research Laboratory.

October 9, 2019

WSU research shows that coffee grounds, usually viewed as a waste product, can be used to form a new, stronger type of plastic.

Poly‑lactic acid (PLA), derived from corn starch, is used in medical supplies and for 3D printing, said Yu-Chung Chang, research lead and Ph.D. candidate in material engineering.

On its own, PLA is brittle but when combined with oil coming from used coffee grounds, it’s more sustainable and cleaner, he said.

“What we use is actually the waste part of the waste, where it has almost no monetary value,” Chang said. “But once we add it into our 3D printing subject, and it becomes something better.”

Oil can be extracted out of the coffee grounds to turn into biodiesel, which in turn is created into a roll of string-like plastic, Chang said.

The researchers used a 3D printer patented by a WSU alum 30 years ago to create test objects out of the plastic, like a small cube, he said.

The objects are tested for how much impact they can withstand, he said.

When the researchers combined 20 percent of the coffee extract with PLA, the toughness of the plastic increased by 400 percent, Chang said.

Chang’s vision for this discovery includes using the new plastic for sports equipment, he said. Chang hopes one day he can create a customizable shin guard that can be thrown out in the garden when a player is done with it.

“The coffee mixes very well with the PLA for this use,” said Cheng Hao, Ph.D. candidate in material science.

Adding a waste product to the plastic keeps the cost down and makes it almost completely biodegradable, Chang said.

Hao said in the research field 3D printing is cost-intensive.

Chang said he was inspired by a company in Taiwan that uses coffee grounds to make fiber that is sold to apparel companies.

“This is basically from a source that we have, literally infinite amounts,” he said.

The team has not done any cost calculations yet, but it will be cost-effective, Chang said.

A challenge the researchers faced included making sure bacteria or fungus does not destroy the plastic since it’s natural-based. Research started about a year ago, Chang said.

“There is no burden to our environment,” Hao said.

The researchers are now investigating how long the plastic takes to degrade into the soil. As of now, it takes six months in the right conditions.

“There is a lot of plastic problems in the world,” Chang said. “As tragic as they are fixable, you can reverse the trend if you start having scientific discoveries.”

Researchers created a small cube out of plastic and coffee grounds to test its strength. They found that it is tougher if coffee grounds took up 20 percent of the material.