Changing the treatment of latino/a youth

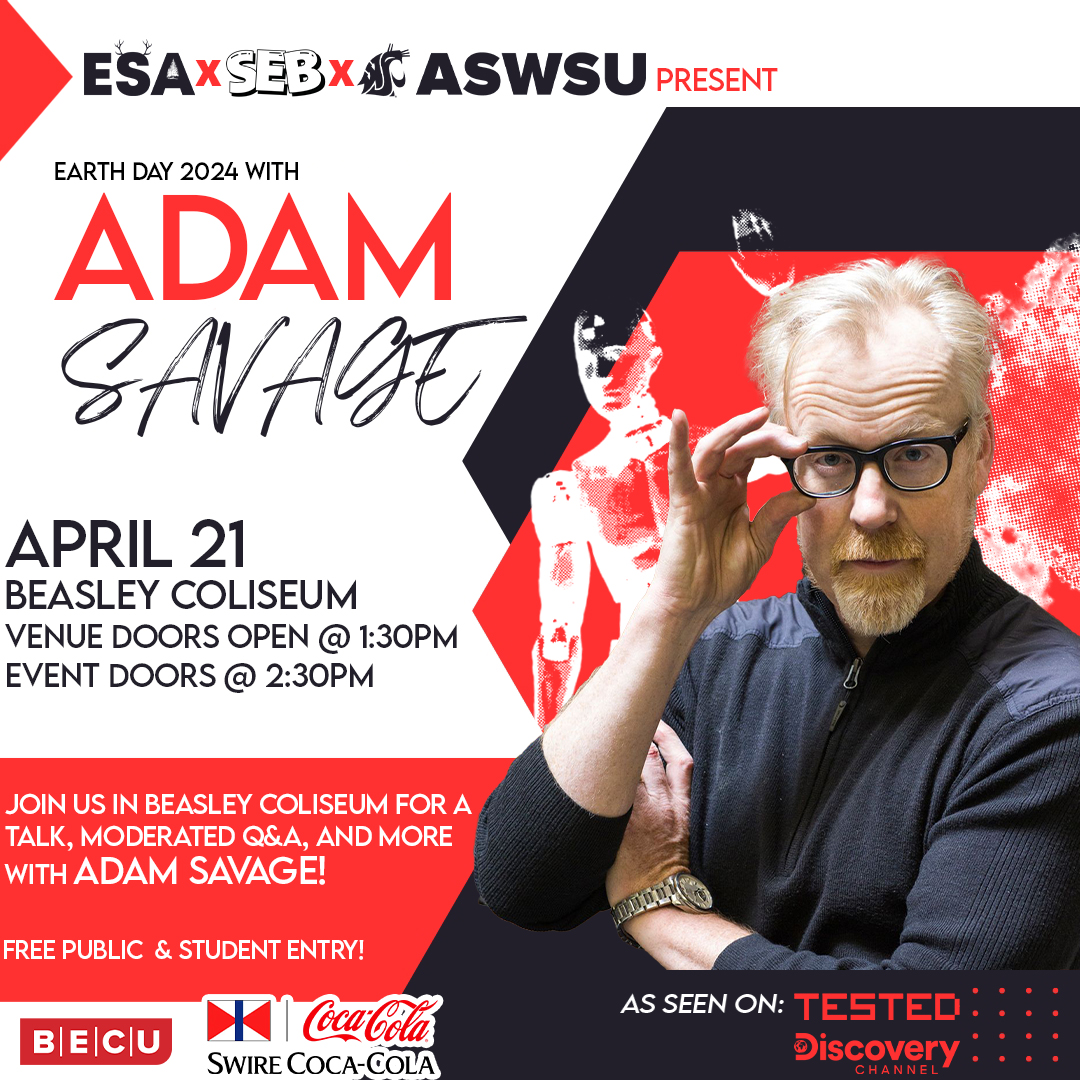

Maria Chavez outlines her experience in political science during her lecture in Bryan Hall on Tuesday, Oct. 27.

October 28, 2015

Many undocumented people grow up in the United States believing they are American, only to find out later in life they are not counted simply because they do not have a Social Security number.

Maria Chavez, associate professor of political science at Pacific Lutheran University, explained the importance of real immigration reform in America through her experiences and understanding of immigration and social reform politics Tuesday afternoon. Her lecture was titled “De-Americanization of Latino Youth,” and was hosted by the Foley Institute as part of its Coffee and Politics series in Bryan Hall.

Chavez got her start in political science at the California State University Chico’s College of Social Science, where she obtained her bachelor’s and master’s degrees. There, she struggled to find people who would support her thesis and desire to survey people about immigration reform and policies. Chavez furthered her research at Washington State University, where she obtained her Ph.D. in 2002.

Her history has shaped how she views politics involving the Latino population in several ways. Her parents did not complete their public education, and her father and mother worked in fields. She attended a school in California and was on a vocational track that was severely limited. The amount of Latino students that actually graduated from her high school was negligible, and the amount that went on to pursue higher education even more so.

This reinforced her interest in studying social reform and immigration. She stressed the importance of immigration reform and noted the lack of real legislation to solve the issue, citing legislation like Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and the Dream Act.

Legislation like DACA poses only a short-term fix and not a long term solution for immigrants. It allows immigrants who come to the country as children an allotted two year deferred action time where they can live in the United States legally and be employed. After two years, they can apply for a two-year renewal.

This, however, is a gamble else for undocumented persons. They show all of their documents to the federal government, where they and their family live, how many people are in their family and so on, subjecting their loved ones to the scrutiny and legal judgment of immigration authorities.

Though the DACA is a short-term gamble, legislation like the Dream Act presents longer-term solutions. Chavez explained how it allows undocumented students to not only pay in-state fees to attend a college or university, but also to help them acquire federal aid. This takes a huge burden off of undocumented students who have had to pay all of their tuition and fees on their own.

This works as a conditional path to citizenship for undocumented children who want to pursue education past high school, she said. However, only a few states – Washington is one of them – have implemented their own version of the Dream Act.

Legislation hasn’t been complicated at the federal level where it needs to be, Chavez said, because Congress is slow to listen and even slower to act.

“We don’t have an un-documentation problem; we have a legislation problem,” she said.

Reporting by Corinna Thornton