Amaan is a freshman majoring in Marketing. He played soccer for eight years.

Born under Jim Crow

Activist heard “I Have a Dream” in person, helped organize “Freedom Summer,” lived through segregated schools, public spaces

March 4, 2020

Terry Buffington recalls her days as a child, she would hear her parent’s whispers about hangings and lynchings that happened around her community.

“I know racism up close and personal with vivid memories of segregation, delapidated housing, inferior school system, racial violence and the [Ku Klux Klan],” she said.

A retired anthropology professor and a sixth generation Mississippian, Buffington has devoted her whole life to fight for equal rights for African Americans.

Born and raised under Jim Crow laws in a small community in West Point, Mississippi, Buffington attended segregated schools, churches and drank from separate water fountains.

“When the Civil War was over, my people walked off the plantations with what they had on their backs and took on the names of their masters,” Buffington said.

As black children, Buffington and her brother were taught how to act in front of white people and to step off the sidewalk when they approached them. They would have to enter through the back doors of certain public places such as restaurants and libraries.

This period in U.S. history is commonly known as the Jim Crow era, named after Jim Crow laws, a political system based on racism, poverty and ignorance that served to maintain white supremacy, while limiting the opportunities available to African Americans.

Emmett Till was a 14-year-old African American boy who was lynched and killed in Money, Mississippi by two white men because he was accused of allegedly offending a white woman at a grocery store.

This incident took place just a few miles away from where Buffington and her family used to live.

“Growing up with the fear of knowing you could be snatched and beaten up and hanged at any time was a constant fear among the African American community,” Buffington said.

Activist Terry Buffington

Noticing all these signs of distress and tension in the African American community around her, Buffington at an early age decided to educate herself, stand up for her community and fight for what she believed was right.

At the age of 15, Buffington joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. The SNCC was a civil-rights group formed to give younger blacks more of a voice in the civil rights movement.

Buffington, along with other volunteers of the SNCC, were part of the 1963 march on Washington where they witnessed Dr. Martin Luther King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

MLK’s stance on non-violence and equal rights inspired the SNCC to take part in the Mississippi Summer Project of 1964.

“African Americans faced violence and intimidation when they attempted to exercise their constitutional right to vote,” Buffington said. “Poll taxes and literacy tests designed to silence black voters were common.”

Freedom Summer leaders chose Mississippi as the site of the project due to its historically low levels of African American voter registration; in 1962 fewer than seven percent of the state’s eligible black voters were registered to vote.

Buffington and other volunteers of the SNCC were constantly monitored and followed by local KKK members. They encountered heavy resistance and their meetings were often disrupted by the police.

One summer afternoon during the project, Buffington and other members of the SNCC were gathered at one of their freedom houses. The house was shot at by local KKK members which caused mass fear among the members.

This made many members go into hiding for a while but that didn’t stop their fight for equality.

The national attention the Freedom Summer gained for the Civil Rights Movement helped convince former President Lyndon B. Johnson and congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which ended segregation in public places and banned employment discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex or national origin.

These efforts also helped push lawmakers to pass the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

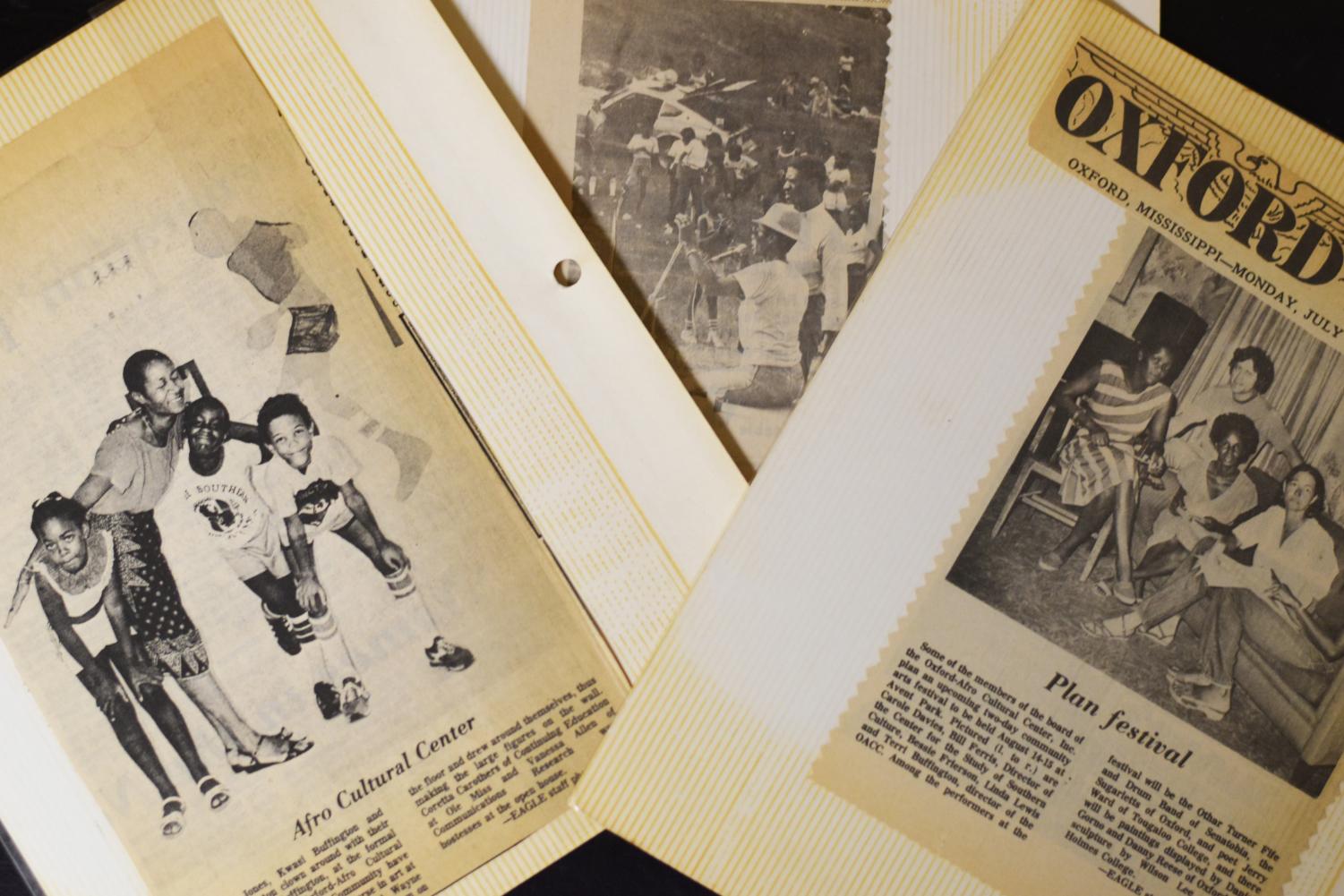

For most of her life Terry Buffington was involved with organizations whose aims are to help black people politically and culturally. In 1979, Buffington founded the Committee for the Promotion of Black Art, which later became the Oxford-Afro Cultural Centre.

The purpose of the program, Buffington said, is to expose black people, especially children, to black art and culture, helping fill a void in their education.

As part of her work with the program, Buffington said she met performers and artists such as Jessie Mae Hemphill, Odetta, the Staples Singers, and Bill Ferris.

As the director of the committee, Buffington said she actively worked to bring different African American artists, musicians and poets from across the country to promote black visual and performing arts.

“Black people have made great contributions in music, art, dance and literature and we staged many festivals as a tribute to the richness of black culture,” she said.

While a lecturer of anthropology at Mississippi State University, Buffington encountered various forms of discrimination from her superiors.

She said she was constantly monitored by the dean and other professors because she taught anthropology in a way that made her students dig deep to the root causes of racism and the way it was institutionalized.

“As an anthropologist, one of the things that we try that we do within the community is build trust,” she said.

Buffington criticized the modern education system and said there is lack of information and knowledge being passed on to youth regarding slavery and the struggles of African American people.

“It’s not just black history, it’s American history,” Buffington said.

Buffington’s stance on modern day racism revolves around police brutality and economic disparities.

“Back in the days, black people used to get hanged and lynched as a form of racism but these days, we’re being shot down on the streets,” Buffington said.

Buffington said she continues to spend her life teaching and educating people because she believes the more knowledge someone acquires the better because they can deal with racism and ignorance in their community.

“Even though Jim Crow Legislations are long gone, I can still feel his ghost lingering around our community,” Buffington said.