Professors highlight gap between science, public

Lawmakers, public could do more to support science

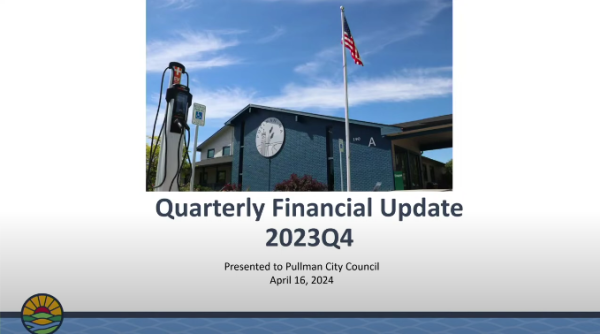

OLIVER MCKENNA | THE DAILY EVERGREEN

Professors Patricia Hunt, left, Kristen Intemann, center, and Steven Steher answer questions from the audience after their Foley Talk Tuesday night in the CUE.

February 14, 2018

Three professors argued in a Foley Institute talk Tuesday that there is a disparity in understanding between scientists, lawmakers and the public, leading many to reject scientifically sound ideas.

Kristen Intemann, a philosophy professor at Montana State University, said people have a tendency to believe what they want and seek information to confirm it.

“About 50 percent of U.S. public believes that climate change is happening as a result of human activity, whereas an overwhelming majority of scientists believe that to be the case,” Intemann said. “Despite the fact that there is a big consensus among scientists, there seems to be resistance to both believing it, and policies that people think would follow from that science.”

Intemann said another example was that despite virtually no evidence of a connection between vaccines and autism, there seems to be a persistent fear that some link exists. An increasing number of parents are disregarding the advice of pediatricians and choosing not to vaccinate their children, she said, bringing back some sicknesses in concerning numbers.

“Perhaps the problem is not that the public is stupid, or even that scientists are bad communicators to the public,” Intemann said, “but that we need to have scientific practices, institutions, that facilitate and maintain trust in scientists, even among scientists themselves, because no one can be an expert on everything.”

Patricia Hunt, a professor in WSU’s School of Molecular Biosciences, said the U.S. is falling behind other countries because of the way it has invested in science compared to others. She said she thinks the U.S. is giving up its place as a scientific leader.

“I’m worried that we’re not investing in ways that will keep us competitive,” Hunt said. “China and India are spending tons of money, investing in infrastructure, buildings for research institutions and grant money for scientists.”

She added that lawmakers do not always lead the public in the right direction when it comes to understanding science.

“We deal with facts and data to understand what reality is,” Hunt said. “We are politicizing science, and it’s my opinion that really politicians and industry are not the people who should be interpreting science that we do.”

Hunt said she hoped to see the next generation of scientists better trained than those of her own.

Steven Stehr, a WSU political science professor, said lawmakers and opinion leaders attack science on certain issues to defend their worldview. He specifically pointed to Portland voters opposing putting fluoride in their water supply.

“They did it on the basis that they didn’t want government putting chemicals in their water,” Stehr said, “even though there were demonstrated scientific benefits.”

Intemann said scientists have a responsibility to improve public trust, specifically on climate issues.

“Instead of just communicating that there is an overwhelming consensus about climate change, it might be helpful to communicate the features of the research that make it trustworthy,” Intemann said. “Such as the fact that they have the research from all different kinds of areas that are all collecting evidences that seem to converge on the claim that the average temperature is increasing.”