Professor talks political polarization, foreign policy

Members of parties tend to align views with their platform, speaker says

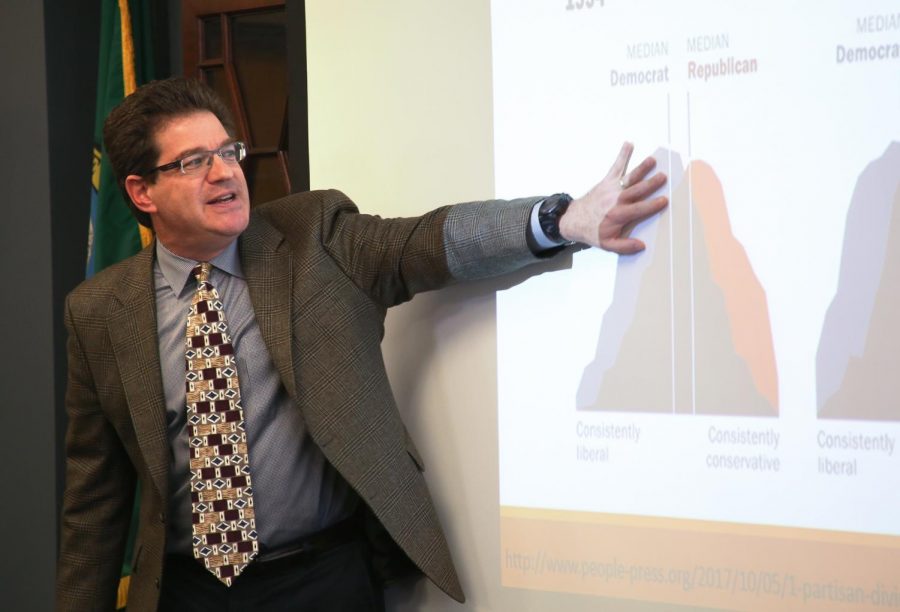

ABBY LINNENKOHL | THE DAILY EVERGREEN

Kenneth Schultz, professor of political science at Stanford University, explained the declining bipartisanship over the topic on the use of military tactics and other various issues Tuesday in Bryan Hall.

October 3, 2018

The Foley Institute hosted Kenneth Schultz, a professor of political science at Stanford University, for a talk on the polarization of American political parties and their effects on foreign policy Tuesday.

Schultz said in the last 20-25 years, the U.S. has seen unprecedented levels of political polarization which in turn requires the president to make more unilateral foreign policy decisions, leading to a destabilization of U.S. international political power.

“The difference between the Republican and Democratic positions diverge quite dramatically, starting really in the late 70s and the divergence is reaching levels that really haven’t been seen before,” Schultz said.

Polarization can be measured in several different ways, he said. One is by looking at where self-identifying members of a specific political party fall on certain issues.

Over time, members of different parties have more closely aligned their views with the rest of the party. For example, a person who identified as a conservative in the 1980s might be more likely to hold liberal viewpoints on certain issues than they would today.

“The center where there used to be overlap in the positions of the two parties is now gone,” Schultz said. “This has me very worried about what’s going to happen to American foreign policy in the future.”

Polarization affects how the opposition party, the party not of the current president, responds to executive military actions or diplomatic agreements, he said.

Since the mid-20th century, Schultz said the opposition party has been increasingly less likely to support executive military actions, but this does not prevent the president from applying force.

Instead, the president will be more likely to employ low-cost, low-risk means of military intervention when he or she does not have congressional support, Schultz said. These low-cost interventions usually take the form of airstrikes or efforts in which no American soldiers are on the ground.

These actions are not intrinsically better just because American lives are not in danger, Schultz said. He said they often leave civilians on the ground worse off than before and sends a message to the country’s adversaries that we are divided.

“Obviously nobody wants to throw away American lives needlessly, but when you make this choice of shifting to air-only strategies, you are making a choice in some cases to trade away military effectiveness,” he said.

Polarization also destabilizes foreign policy with allies by forcing presidents to negotiate executive agreements instead of treaties, Schultz said. Treaties must be ratified by two-thirds of the Senate, while executive orders only require the president’s signature.

Schultz said polarization has led to presidents breaking executive agreements made by past administrations of the opposite party, causing allies to see the U.S. as unreliable between presidencies.

This was seen most recently with the last two Republican presidents overturning agreements signed by their predecessors, Schultz said. Since taking office, President Donald Trump has overturned three agreements signed by former President Barack Obama: the Paris Climate Agreement, North American Free Trade Agreement and the Iran Nuclear Deal.