Ryan Leaf addiction after NFL career

Former quarterback says the way he handled criticism affected success

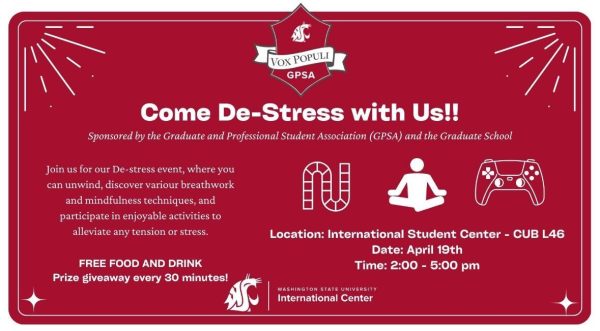

ABIGAIL LINNENKOHL | DAILY EVERGREEN FILE

Telling his story of success, failure, lying and finally changing who he was and telling the truth, former WSU quarterback Ryan Leaf challenges WSU athletes in attendance to hold themselves accountable Sep. 13 in the Cougar Football Complex.

April 22, 2019

Former WSU quarterback Ryan Leaf hosted a talk Friday about his struggles with mental health and addiction following his NFL career.

Leaf said he felt like he was “pretty special” after being drafted second overall in the 1998 NFL draft. He said he was a successful athlete through his youth and ended up being the first and only player from Montana to be drafted in the first round of the NFL draft.

“I thought I was better than everyone because I could play a silly game,” he said.

After being drafted, he said he was paid $31 million, a number he felt was astronomical at the time.

Leaf felt like he had it all. He thought he would play 15 to 20 years in the NFL, but he said his career really ended after his third game.

Leaf said the third game of his career against the Kansas City Chiefs was the worst football game he ever played. But he said it was the way he handled the criticism that determined whether he was a success or a failure.

The next day, Leaf berated a reporter, who he said wrote a negative article about him.

Leaf said as a successful athlete, he had always been given what he wanted and told what he wanted to hear. He felt like he had always had the power to control things around him.

“Consequences were not the same for me,” he said.

Leaf said peoples’ expectations for him were high, and he had the highest expectations for himself. He saw failure as black-and-white rather than an opportunity to do better the next time around.

Leaf continued to struggle in the NFL. He said near the end of his career, he suffered symptoms of depression.

“Instead of asking,” Leaf said, “I quit something I wanted to do since I was 4 years old.”

Leaf said USA Today published a list of the top draft busts of all-time recently. His name topped the list.

“I thought I would disappear into the ether, and no one would care anymore,” he said.

Now, Leaf said his name is used every April as a cautionary tale.

“Don’t draft the next Ryan Leaf,” he said.

Leaf said competition was his first drug of choice, but with football absent from his life, as well as the criticism and judgment he felt, he needed something else to numb the pain and anxiety.

He said that was when he began to abuse painkillers.

“I didn’t want to feel anything,” he said.

This led Leaf down a vicious cycle of drug abuse. Leaf said one of the hardest realities to face was that he spent nearly all of the money he earned from the NFL.

He was living in a small guest house in his hometown regularly using pills.

“I would wake up and if I had pills, the day was glorious,” Leaf said. “If not, I had to search and find some.”

Leaf said the only thing that stopped this cycle was an intervention. He said that was what happened when he was arrested twice in 48 hours for burglarizing homes in search of more drugs.

As a person of privilege, Leaf said the first time he ever felt marginalized was when he was sentenced and given an inmate number.

He said his life in prison was miserable yet complacent because he felt that incarceration was the most fitting place for himself. He felt worthless and helpless until a cellmate changed his perspective.

His cellmate encouraged him to help teach other inmates to read at the prison library. Leaf said he reluctantly agreed to help.

Leaf said he was humbled when 50-year-old men admitted they could not read and asked him for help, showing vulnerability in an environment where it was so rarely revealed. Leaf returned day in and day out to continue teaching.

“I realized I was of service to another human for the first time in my life,” he said.

After Leaf was released, he visited a rehabilitation center and has been sober ever since. He is now involved with sobriety and treatment support networks in California as he continues to help those who suffer from addiction.

Leaf said he has realized what he thought about success when he was young was wrong, and he now feels his life has more value than ever before.

Josh Jackson • Apr 26, 2019 at 12:17 pm

“person of privilege”

Jesus, what a bunch of cucks at Evergreen

Lorie Lucky • Apr 26, 2019 at 8:11 am

So happy to read this article about Ryan Leaf. I remember watching him as the Cougars’ quarterback in his glory days, and I always hoped he would turn things around – and he has. Those times must have been hard on his family as well as himself, because addiction and alcoholism are “family” diseases. Keep it up, Mr. Leaf.

pat k • Apr 25, 2019 at 10:06 am

Happy for him. Some people say he was a bust but those are not people he is working with today. Don’t let other people measure your success and failures. Keep it up Ryan Leaf.

Phil Petersen • Apr 22, 2019 at 6:43 pm

Great article. Ryan Leaf has really turned his life around. And we,from cougar nation are very proud of the person he has become. God bless you.