Heart disease rates decrease in Native populations

WSU study finds that health issues have decreased recently

A study conducted by WSU researchers found that the rates for heart disease in some Native populations decreased in recent years.

November 19, 2019

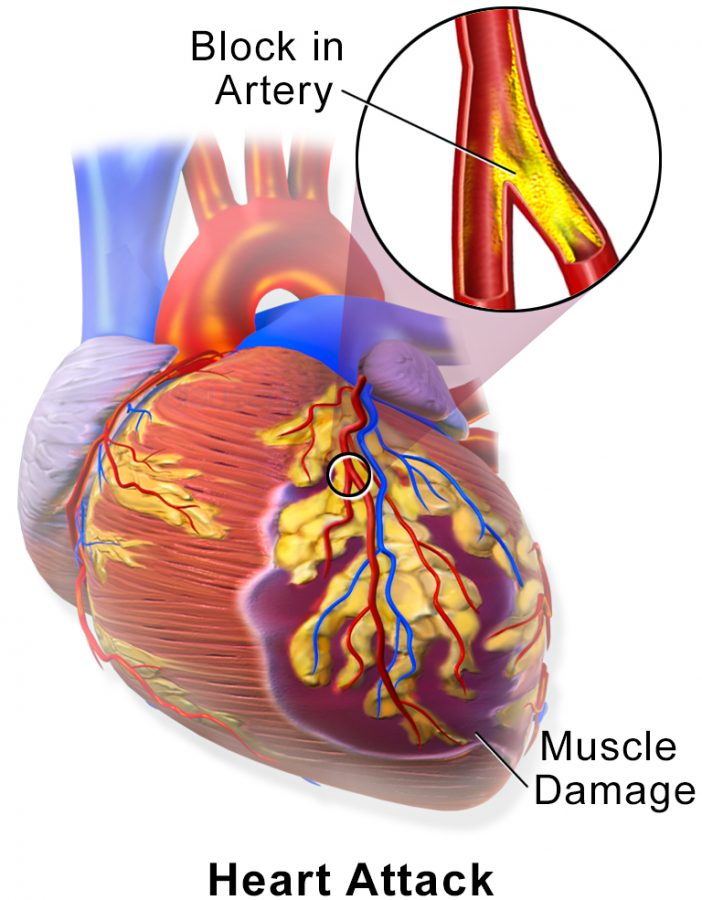

A study conducted by WSU researchers found rates for heart disease in Native Americans decreased in three U.S. tribal regions.

“The federal government has a treaty obligation to provide good healthcare for its indigenous population and historically, that is not the case,” said Clemma Muller, WSU assistant professor and researcher with the WSU Institute for Research and Education to Advance Community Health.

The study discovered that people born more recently had less of a risk for heart disease than those born before them when they compared data for different age groups.

Muller used the example that if someone is born in 1940 and turns 60 in 2000, that person could have a ten percent chance of a heart attack. However, the study found, a person born in 1965 that turns 60 in 2025 might have a five percent chance of a heart attack.

The study analyzed data collected from the Strong Heart Study and the Strong Heart Family Study, which started collecting data in the 1980s. The Strong Heart Study looked at heart disease in about 5,000 Native Americans from three regions including the northern plains, southern plains and the southwest region, according to the research journal.

A total of 13 tribes agreed to participate in the study. Participants were required to undergo a thorough examination, which included taking a blood sample, completing a self-report questionnaire and recording their weight and height, Muller said.

Muller and her team used data from participants ages 30 to 85 years old. The data collected ranged over 25 years, according to the journal.

The study led by Muller also analyzed death records to track how many of the participants died from heart disease, as well as who started the study without hypertension and was diagnosed later.

Muller said the most surprising finding from the study was that women’s risk of dying from heart disease did not significantly decrease like it did in men. The study did not look at why the data showed what it did, but Muller said the team has some theories.

One theory for the results could be that people in the study if found to have high-risk factors for developing heart disease, were given medical treatment, she said.

“If you have good healthcare your heart disease risk goes down,” she said.

Muller said another explanation for the data could be external factors, such as people smoking less, decreasing air pollution and improving the food supply. She said that explanation was not very likely because the Native population still faces poverty, pollution and challenging food supplies.

“It’s important to put resources to study our Native populations so that we can better understand what is happening and how to improve health disparity,” Muller said. “That is really a social injustice that this population is experiencing.”

She said Native Americans do not have the same access to healthcare as most white populations.

WSU researchers, a researcher from the University of Minnesota and researchers from the Strong Heart Study comprised the team, which worked on the project for six months. The National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute funded the study.

The research on this topic is not finished. Muller said she wants to research more about how the risk factors for heart disease impact the trends that were found.