WSU researchers develop sugar sensor

Device not finished, needs to be tested in human simulations

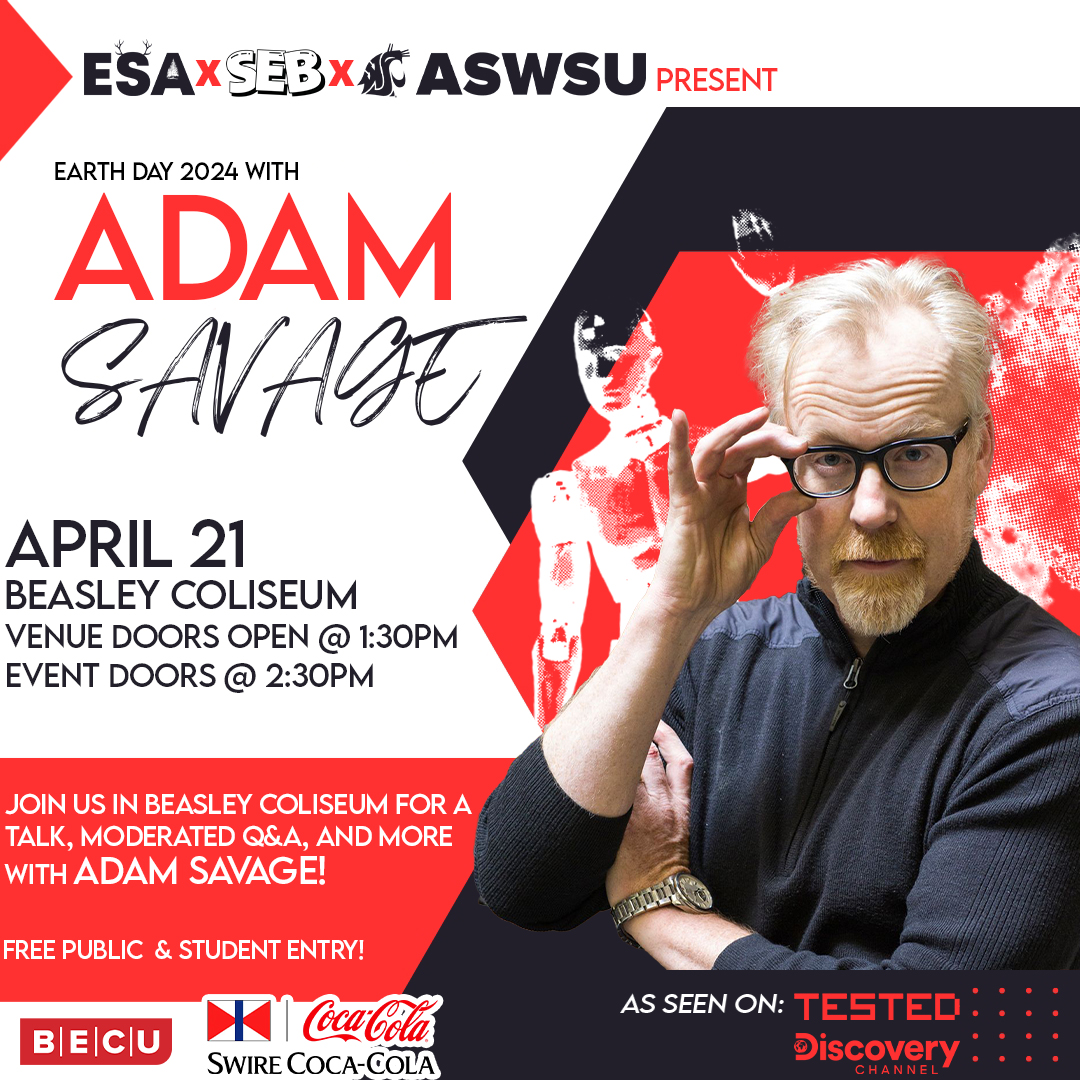

BEN SCHUH | THE DAILY EVERGREEN

Subhansu Gupta, assistant professor, discusses his work in the research and development of a sugar-powered sensor that can be used to detect and prevent diseases.

October 26, 2018

WSU researchers have created a sensor made of a biofuel cell and an electronics component which detects diseases such as diabetes or cardiac problems.

“The novelty in what we have done is that a biofuel cell is not new by itself,” said Subhansu Gupta, assistant professor in the School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. “Electronics are not new. But the integration of the two is what is unique.”

Gupta led the design of the electronics and the integration of the fuel cell with the electronics.

The fuel cell takes glucose from the blood and uses enzymes to extract electrons. The electrons power the electronics, he said.

One of the limits of this technology is that the biofuel cell can only generate microwatts per hour, he said. For comparison, a phone battery generates watts per hour. A watt is approximately six orders of magnitude larger than a microwatt.

The electronics must be able to consume a very small amount of power to be able to work with the biofuel cell, he said.

One thing the sensor does is measure strain, such as blood pressure. It can also measure a heart rate.

“Apple Watch does a heart rate measurement, but it is just measuring the peak of the heart rates,” Gupta said. “There’s a lot more to heart rates.”

Doctors look at the slope, peak and trough of heart rates, among other things, he said.

“When you’re closer to the heart, you can get that information much cleaner rather than being further away from the heart,” Gupta said.

The sensor is not finished yet, he said. The integration of the two components of the sensor is done, but testing still needs to be completed.

“We know how [the sensor] works, but we haven’t shown that it can work inside the body,” Gupta said.

When anything foreign is put into the body, as the sensor would be, there is a risk of blood clotting which could cause harm, he said.

Gupta said the first step in testing the sensor is to use a phantom, which is a simulation that will imitate the environment the sensor will be in. A tank will be filled with a salt-based liquid that is the same density as blood. When the sensor is placed in that, researchers will be able to see whether it is working.

After that test, the researchers will test the sensor in animals. It must be a large animal, such as a pig or sheep, he said. Once those tests are done, the sensor will be tested in humans.

Current batteries are made of lithium-ion. However, Gupta said lithium-ion batteries are not renewable and have a high toxicity to both the environment and the body.

“The idea here is to use the body as a natural battery,” Gupta said. “That way you don’t really have to use the lithium-ion or a synthetic battery.”