Microscope allows three-dimensional reconstruction

New equipment bought by grant, used by life sciences

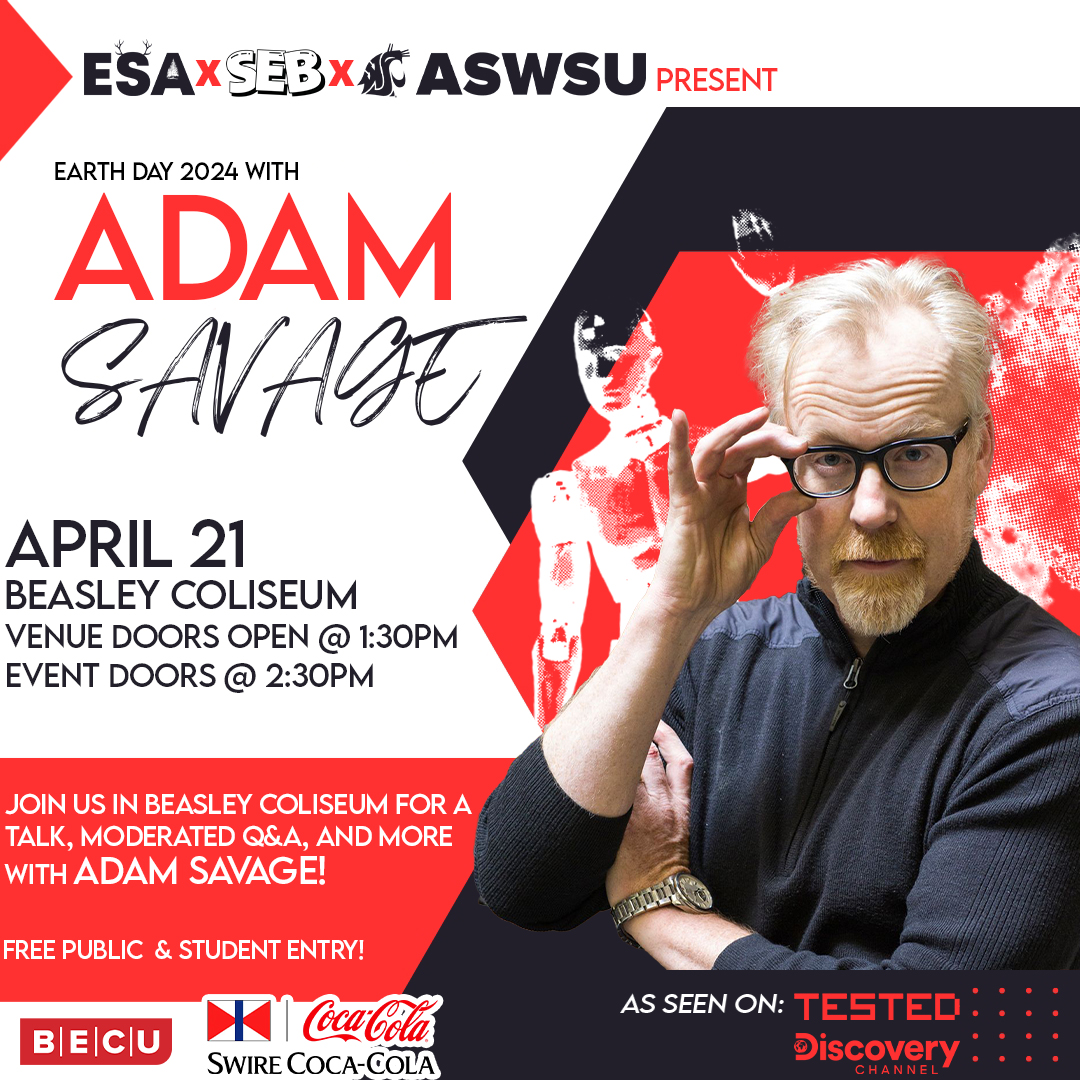

BEN SCHUH | THE DAILY EVERGREEN

Dr. Michael Knoblauch, director of the Franceschi Microscopy and Imaging Center, discusses benefits of electron microscopes on Tuesday.

March 8, 2019

A new microscope is open for student and faculty use at the Franceschi Microscopy and Imaging Center (FMIC).

FMIC staff scientist Daniel Mullendore said the Apreo VolumeScope is a scanning electron microscope (SEM) capable of taking thin sections of a biological sample, resulting in a three-dimensional reconstruction of the sample.

FMIC director Michael Knoblauch said living cells cannot be exposed to the high vacuum used by the VolumeScope. To fix this, Knoblauch said chemicals are applied to the cells to integrate all of its cellular compartments. This process is called fixation.

Mullendore said users must complete the one- to two-week-long fixation protocol before inserting the sample into the VolumeScope.

He said the protocol consists of taking the biological sample and soaking it in various chemicals to enhance the contrast of certain structures within the cells. Once the sample is electron opaque, or light enough to see under the microscope, it is dehydrated in a solvent like ethanol or acetone.

Mullendore said the dehydrated sample is then embedded in a plastic resin. The sample is examined on a transmission electron microscope (TEM), a microscope that uses the electrons in a sample to scan the whole image, to determine whether or not the fixation is suitable to proceed with the experiment.

Knoblauch said it takes around 15 minutes to determine whether or not the sample is integrated enough to be used. If it is not, the user must restart the entire process.

“Preparation is a critical thing in electron microscopy for life sciences,” he said. “It takes a long time to prepare and a very short time to see it’s not good. Then you have to start over.”

Mullendore said the fixation protocol for plant tissue is still being perfected because the one currently being used was designed for animal tissue, specifically rodent tissue.

“Fixation types of animals versus plants can differ quite a bit,” he said. “The plant tissues require a different fixation.”

Mullendore said when the sample is suitable, the sample block is mounted onto the SEM. The block is trimmed and coated with coal to make it more electron-conductive.

Knoblauch said the SEM shoots electrons on the surface of the sample while scanning over it. It slices several nanometers off the block sample and scans it once again. The process is repeated hundreds to thousands of times.

“You can reconstruct 3D volumes, not just single 2D shots,” he said. “It can extract information such as the volume of cells and the number of specific organelles.”

Mullendore said the result is a high-resolution image.

The SEM can be a destructive process, Mullendore said, as the block faces are sucked up into debris traps after being scanned. The debris is vacuumed out after every experiment.

A grant helped purchase this new technology, Knoblauch said. The equipment was delivered by Nov. 2018, and it took several months to be installed. Knoblauch and his associates were then able to use the microscope for three to four weeks before opening it up to the public.

Mullendore and FMIC microscopy specialist Valerie Lynch-Holm will train students on the sample preparation process and the microscope operation. Prospective users can make appointments at the center, through email or on the FMIC website.