OPINION: Schools should educate on tribal sovereignty

Most Americans don’t know how reservations work, are treated by government

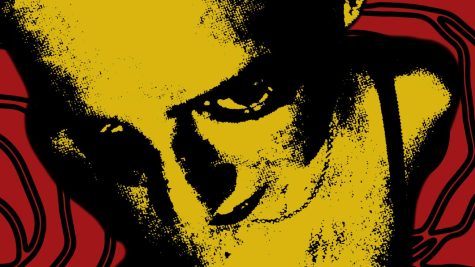

HSING-HAN CHEN | DAILY EVERGREEN FILE

Retired local Michael J. Penny performs with other indigenous members during the Indigenous People’s Day festivities on Oct. 14 on the steps of Todd Hall.

November 1, 2019

Our schools should teach about Indian reservation sovereignty.

Ken Lokensgard, assistant director at the WSU Center for Native American Research and Collaboration, said many Americans have misconceptions about even the most basic elements of reservation sovereignty: what tribes can and cannot do with their land, what benefits they receive from the government and if tribes have sovereignty at all.

This widespread lack of knowledge is concerning.

We should add education about American Indian reservation sovereignty to every state’s education curriculum. Understanding this information is important since reservations and the people living on them play such a large role in the U.S. today.

Over 5 million American Indians and native Alaskans live in the U.S., according to the National Congress of American Indians. There are about 326 American Indian reservations in the U.S., collectively adding up to about 56 million acres, or roughly the size of Idaho, according to the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

The laws and treaties around reservations are quite complicated. In short, reservations maintain a quasi-independent status within the U.S.

Each reservation has its own relationship with the federal government based around a treaty signed between each tribe, in some cases a confederation of tribes, and the federal government.

Lokensgard notes that these treaties are usually like one another. Often reservations run their own police. They have tribal governments. They oversee economic growth and development in their own reservation and run educational and social services.

However, reservations have little say over their own lands when it comes to things that impact the lands but are not built on the actual reservations, such as pipelines or dams. This has led to controversy, as many public works projects impact reservations, but the people on those reservations are not always consulted. This begs the question: would having more education about sovereignty reduce these kinds of issues?

“I do think it would help. I think even our lawmakers don’t always have a firm understanding of tribal sovereignty,” said Faith Price, director of WSU Native American Student Services.

We need education about these institutions and laws because of their relevance today, and because they make up a crucial part of our nation’s history.

One of the reasons why the Constitution replaced the Articles of Confederation was because of the individual states’ inability to effectively interact with American Indians.

In some cases, the states acted respectfully toward them, and in other cases, the states caused trouble with them by unauthorized settling in their land. However, a larger problem for the early U.S. was the sheer power that some tribes had at the time; states by themselves could not win a war against Indian nations.

The Constitution enabled the federal government to make treaties with American Indian tribes on a massive scale and prevented states from acting without federal approval.

The relationship between the federal government and tribes is deeply complicated and painful and plays a vital role in our country’s history. It is something we cannot ignore.

Diana • Nov 3, 2019 at 5:15 pm

I think we are very uneducated and need true history on how this country started. I for one an very interested as are many of my acquaintances.