Breaking down the ethics of faculty-authored textbooks

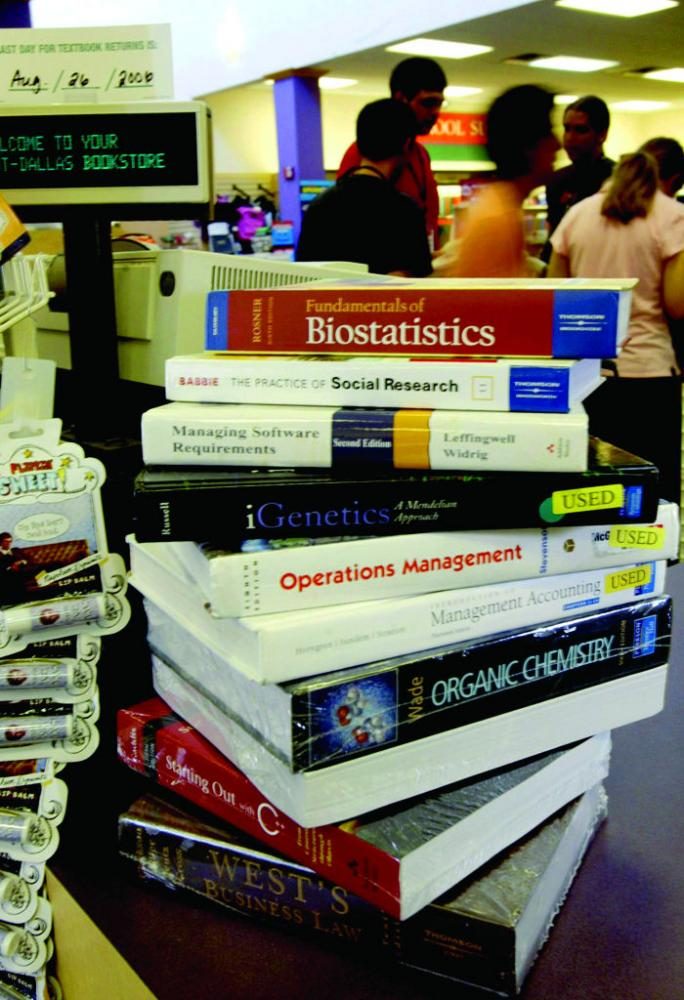

Textbooks at the University of Texas at Dallas bookstore in Irving, Texas, August 10, 2006. Research shows textbook prices have increased at four times the rate of inflation since 1994, with no end in sight.

February 25, 2016

Recently, some amount of attention has turned to the ethics of faculty promoting the sale of anything which they directly benefit from, namely textbooks or required reading which they authored.

Though the extent of faculty use of books they authored is in question and not easily ascertained, students are reasonably concerned that they are getting a raw deal when they get assigned something with their teachers name on it. But to what extent do teachers benefit?

As reported by the Daily Evergreen Feb. 19, the WSU faculty manual states that faculty cannot make such promotion out of self-interest, whether monetary or for status.

“Requiring the use of faculty authored materials must only be done to promote appropriate educational goals. It must not be done for personal benefit or to obtain special privileges for faculty,” the manual states.

According to the Washington State Executive Ethics Board, faculty who assign their own work or are integral to the decision to have the work assigned waive any right to profit from the sale of the work or to collect royalties.

This is, however, not applicable if another faculty chooses to assign their work, or if an external committee assigns the book as course work.

Furthermore, such ethics laws of course have barriers, as special privileges for faculty are a vague occurrence to legislate.

In any competitive university job, publishing in academic journals is a political must in order to stand out among your competitors or to edge along the eternal route to tenure.

It follows that publishing a textbook which is frequently circulated, particularly in one’s own place of work, stands to provide personal incentive in the form of social currency.

It is impossible, then, to completely separate a teacher from the benefits of their book’s circulation. The question must then be posed as to how best to demonstrate that a book is being chosen primarily for its educational potential and not for whatever personal benefits there are for the teacher.

This poses another question: is it possible to quantify educational merit of a given piece over the body of existing work?

Though perhaps the incentive for academic standing is a more prevalent pressure in the STEM fields, the possible manipulation of students is something I worry about far more in one of my own fields of study, creative writing.

Out of my three years and seven courses in creative writing, only one has gone by where at least one assigned reading didn’t belong to a professor’s friend or peer.

The argument against teachers who assign each other’s work is ultimately slim. Regardless of any potential favor-seeking, it is a healthy expression of communication and feedback loops throughout the academic community.

Though the potential exists for isolationism and a certain kind of ivory tower syndrome, the benefit to having a self-aware and responsive community outweighs this potential.

However, if a professor uses their own work in class without being able to demonstrate a sense of necessity to their class, the act appears self-serving regardless of its legality.

That single class without a professor who brought in their peer’s collection of prose was also the first where I had class time dedicated to a demonstration of the professor’s own collection of poems. The response was lackluster; regardless of the quality of our professor’s work (which is not a subject I will broach here), the general feeling in the room was discomfort.

We were asked how the poems made us feel.

“Like I paid for an advertisement,” a student next to me whispered.