Student athletes lack compensation

March 21, 2017

Critics of the NCAA consistently refer to the institution as having a monopoly over the cartel of rules and regulations athletes must follow.

Naturally, a non-profit organization with $200 million annually retained in endowment funds is bound to spark discussion over where its money is going.

However, the debate many people are partaking in isn’t necessarily about the NCAA’s profitability. The debate is more about how the organization is making its money and not about its retention.

The NCAA uses a quasi-endowment, which invests funds retained from institutional resources rather than expending them, and established its endowment more than a decade ago with the goal of promoting long-term stability.

The NCAA men’s basketball tournament, otherwise known as March Madness, generates about $900 million in revenue annually. Filling out a bracket has become so popular that it is essentially a requirement for any casual sports fan.

The success of the three-week event, however, raises a question of ethics. At what point, if any, does the financial success of the tournament require the NCAA to compensate its athletes for helping generate this surplus of revenue?

After all, there’s no such thing as March Madness without the 10 basketball players lining up across from one another on the court. That’s the main argument in favor of paying college athletes.

Ethically speaking, the counter-argument is that these men and women aren’t simply athletes. They’re student-athletes, the emphasis being on the student coming first.

I found this topic to be fairly complicated, so I sat down with WSU sport ethics professor Scott Jedlicka to discuss the issue.

A graduate of the University of Texas at Austin, home to one of the most highly-regarded sport management programs in the world, Jedlicka said the current system of amateurism is unrealistic.

“So long as big-time college sports [football and basketball] are operated as commercial enterprises, then it is unethical to fix the price of the labor that produces those goods,” Jedlicka said.

Basically, Jedlicka said student-athletes on scholarship are limited in the amount of pay that they can receive based on the price of the scholarship received.

If, for example, an athlete was to outperform the value of their scholarship, he or she currently does not receive any further compensation. In fact, the NCAA limits student-athletes from earning sponsorship or endorsement deals from sponsoring corporations.

The problem here is that the current formula does not take into account those not receiving scholarships, walking on to their respective team and outperforming their scholarship.

To compound matters, if the United States were to join countries like France, Germany and Mexico in guaranteeing free or relatively low tuition for public college, there would be no value of athletic scholarships.

Jedlicka also said the goal of college athletic departments does not strictly revolve around academic success.

“There’s an interesting argument that says regardless of who was wearing the jersey, it is the jersey that is generating the value in the commercial enterprise,” Jedlicka said. “It is not the athletic skill. If that is indeed the case, then why do universities recruit? Why do we care whether we have someone to replace Luke Falk or Gabe Marks?”

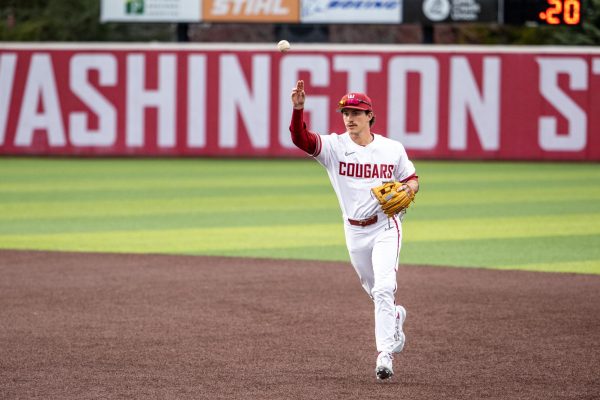

Cougar fans comprise a strong fan base. Win or lose, the WSU identity never leaves an individual, it’s just that everyone wants to win as much as possible.

What a fan witnesses his or her favorite athlete doing on the playing field certainly trumps performance in a math or English course. Athletic departments want to win more games than their rivals, draw up fan revenue and boost morale. In the big picture, the ultimate goal is to make money.

Jedlicka said his final argument on the matter is the idea that the NCAA should enact a spending cap on athletic departments to crack down on hasty spending.

“If they exceeded that, then they would be subject to sanctions,” Jedlicka said. “This would be a way to reign in athletic spending and by lifting limitations on what athletes could earn, allow market forces, competitive forces to set the price of that labor. Universities would have to be financially responsible in the same way we expect of athletes.”

For athletic departments operating in the red, notably WSU, ditching the quasi-endowment fund, instituting a spending cap and finding better ways to compensate athletes might be a step toward solving these issues.