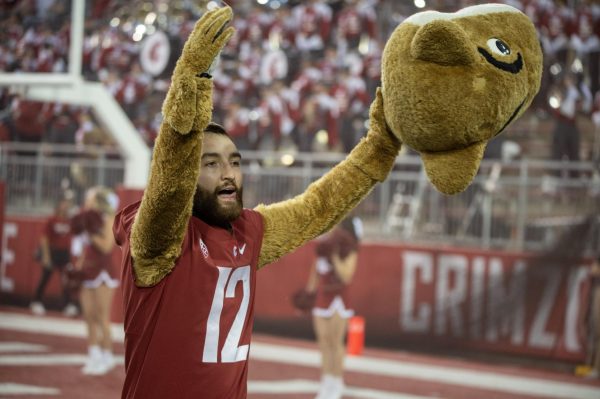

Battletested: Gabe Marks’ story

October 30, 2015

He stands with his back against the wall, casually leaning against it while running his fingers through his jet black hair, attempting to tame it before the camera begins to roll. “Midterms, man,” he laughs as his hair refuses to relinquish its unruly curls.

He pulls the collar on his polo shirt, emblazoned with the Cougar logo, so it is straight. He takes a breath and begins to speak. His posture and unhurried tone allude to a casual Gabe Marks, but do not be deceived.

His eyes are fervent; they appear to spark despite their deep brown color, the only clue to the intensity that surfaces most often on the field – and when he gets the chance to talk about others.

“Who inspires me? Everybody. People that do cool things. Winners inspire me. People that don’t give up. Everybody has got their own thing, everyone is an inspiration once you get to know them,” he said, leaning forward.

It seemed simple to the redshirt junior wide receiver, the answer came as easily to him as the word Superman might to a five-year-old. It is people and the game that fascinate him. He is magnanimous in his treatment of others, a trait that seems uncommon among athletes.

Each Saturday, it’s the masses filling stadiums to the brim that have a front row seat to the singular focus and passion that results when a person gives every fiber of their being over to a pursuit. When it comes to Marks, there is no such thing as good enough, good or anything less than the best.

“I always want to be the best receiver in the country,” Marks said.

Unlike many athletes, it is not arrogance and selfish lust for the spotlight that fuels his desire. Marks does not want to be the best for the attention – he has experienced the good, the bad and the ugly that comes with being an elite athlete in that respect; he genuinely wants to better himself, for himself. Marks does not seek the recognition that comes with it, although he doesn’t mind it.

“I like making plays on TV, that’s kind of my thing. And also helping the team,” Marks said. “I feel like if I make plays then I’m helping the team.”

He does not apologize for his confidence; but, then again, he has no reason to. This season he has been a pillar of the offense. Against Arizona, he caught four touchdown passes, setting a school record. He currently leads the Pac-12 in receptions and touchdown receptions and is second in receiving yards. In the two games prior he tore defenses apart, catching two touchdowns each game. He was nominated to the Biletnikoff Award Watch List prior to the Oregon State game.

As the nation takes notice of the inhuman statistics and talent, Marks puts his head down and continues to work. He always seems to have a chip on his shoulder, a chip formed by circumstance and fed by his relentless drive and burning ardor to prove to himself that he is on his way.

“You never actually know if you actually belong at this level until you get in there and it happens,” Marks said. “Then you know, ‘I can do this.’ That is important.”

In the rare instance that he finds himself outmatched – be it by an injury or an opponent – his tenacity and grit and utter refusal to quit prohibits any force from stopping him on the field.

“Say someone gave you the chance to go up against an Olympian and you’re only in high school, you might get a little nervous. You might get a little intimidated, but that’s not in his DNA,” said Ron Allen, Marks’ trainer since eighth grade.

The equivalent of an Olympic opponent did not always come from the field.

When Marks was nine years old, his father was murdered in his hometown of Venice, California. Marks had only played football for a season before one of his biggest fans was no longer there.

“He really didn’t speak about it,” Marks’ mother Jordanna Gersh said. “He took all his anger, frustration and disappointment about his father being gone out on the field.”

When football season arrived the next year, the game became an outlet and a healer. Each exhausting practice and game, he worked to find a release as much as he worked to be one of the best. The field was a place of solace, but it was not long before football became much more than therapy.

Although football became more of a fervent passion than therapy with time, he continued to spring out of the tunnel each Saturday wearing the number nine, a reminder of how old – or more aptly how young – he was when his life was altered.

By the eighth grade, football was consuming every waking moment Marks was not spending in school. He would get up early every morning for football workouts and practices while his friends that were living with he and his mother were still asleep.

Marks would leave the two bedroom apartment that he, his mother and four of his friends shared and drive to B2G Sports, where he would work out with high schoolers bound for collegiate programs across the country.

Amongst those older athletes, it was again the absence of any fear that set him apart.

“It’s his willingness to compete on every level,” Allen said. “That’s rare.”

He has always been willing: willing to work harder than anyone to reach the top; willing to sacrifice his childhood; willing to put it all on the line for 60 minutes each week.

The one component of the player he is now that was completely altered was his willingness to put his body on the line for a first down conversion, another ten yards, a touchdown.

By his own admission, Marks did not like the contact aspect of football initially. He played basketball as a boy rather than Pop Warner football. Marks is not a giant by any means, even now. He stands 6-feet tall and weighs 190 pounds, but before he had matured, keeping weight on his small frame was difficult.

“He was always considered smaller then, or very frail, not as heavy. He always had a hard time keeping on weight. So I think that played an impact on him not wanting to get hurt,” Gersh said. “Even at Venice High, he did not want to get hit. He would do everything in his power to get the touchdown or complete the play without getting hit.”

It was not until he reached Washington State that he began to welcome contact on the field. During the Oregon State game, Marks thrice left the field limping or woozy, and returned each time.

On a particularly brutal hit, Marks jumped to meet a high pass and was sandwiched between a linebacker and a defensive back. In typical Gabe Marks fashion, he held onto the ball and was back on the field for the next drive.

Since signing his letter of intent with WSU, Marks abandoned all remnants of caution on the field. During his freshman year, he played in all 12 games. His sophomore year he played in all 13 games, starting nine, and tied for a team-leading seven touchdown grabs.

Then it all came to a screeching halt.

Marks had been struggling with injuries and illness during the off-season, and the winter before, Marks was arrested for his part in a bar fight which resulted in his citation on four misdemeanor charges.

“People think I was an out of control problem kid. I wasn’t,” Marks said. “I made a couple of mistakes.”

Despite the initial disappointment that followed the decision to redshirt Marks, that year off proved to be much needed. In essence, Marks hadn’t known a year that didn’t completely revolve around football since he was in fifth grade.

“He has worked so hard to get to where he is. I’ve never seen a kid work that hard,” Marks’ uncle Greg Chambers said.

While other kids were playing pick-up games of basketball, going to the movies and growing up gradually, Marks was thrust into the fray of being wholly at the mercy of a sport. Every aspect of life was related to football or school until it swallowed Marks. Football became who he was.

“He knows who he is, and I think he’s comfortable with himself,” Gersh said. “Before, I think he thought of himself as a football player named Gabe Marks. I used to tell him, ‘You are Gabe Marks, who just happens to play football.’”

During that year, Marks had many conversations with his grandpa and his uncle, talking through the disappointment and frustration he felt as he was pulled away from the very thing that had dictated his life for the past 10 years.

The sport he loved had exacted a harsh and unavoidable cruelty on him. Having his identity inextricably tied to football helped him to cope with his father’s death and brought him to WSU with a fully-funded education, but it cost him dearly.

“It’s hard. It’s hard when your identity all your life is just that you are this amazing football player that everybody is waiting to see every week,” Gersh said. “I think for athletes what happens is they get into this, ‘I’m going to be forgotten about’ mindset… He was worried with finding his identity outside of football. It was a struggle.”

Having time to reflect and relieve some of the pressure changed him as much off the field as it did on it. He matured. He let go. He found himself more dedicated while maintaining a sense of self away from the game he so loves.

“He smiles a lot more [now],” Chambers said. “There is a sense of lightheartedness that he has now that he didn’t have before.”

Football never ceased to be a colossal part of Marks’ life during that year; it just momentarily stutter-stepped. He contributed to Thursday Night Football and sustained a rigorous work-out routine, his eyes already on the next season.

Now nearly three-quarters of the way through his first season back, he hasn’t skipped a beat. And although that may surprise some, for Marks there is no such thing as regression.

But now, he has a redefined relationship with the game. His time on the field isn’t overshadowed by the fear of being lost among the masses should something happen. He knows who he is, what he is capable of.

“The rest of the world, they know him as number nine, the guy that catches a lot of touchdowns,” Chambers said. “But outside of the uniform, you take the helmet off, he’s an extremely smart kid, extremely perceptive of the world. He is curious, intellectually curious.”

As a sociology major minoring in philosophy, Marks is doing what he always has done: chasing what he loves. His desire to figure out why the world is the way it is, why people are the way they are, does not make him different from many others. It is the time he devotes to studying something that truly interests him while also devoting ungodly amounts of work to football.

For that, he stands alone.

He is as much a football player as he is a scholar. He is as much a teammate as he is a friend. He is unapologetically confident and he is genuine, sensitive and caring. He picks the highest possible goal and sets his mind to it, but is not disillusioned by the scale of it.

In the hallway outside the conference room, he smiles and offers his reasoning behind his desire to be the best, “If I strive for that, it could work out, it might not, but if you set the bar high enough and you fall short, you’ll still fall pretty high.”