Researchers understand way bacterium infects cells

Bacterium considered threat by World Health Organization because of antibiotic resistance

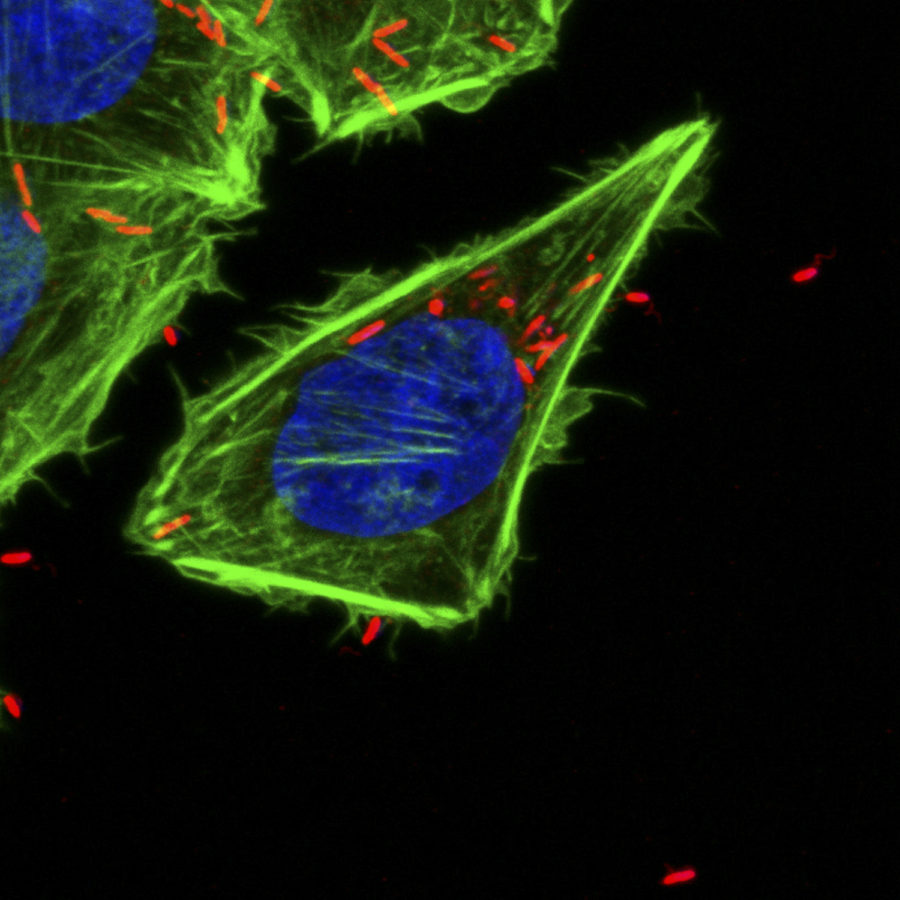

An intestinal cell is infected by Campylobacter jejuni, a bacterium that causes food-borne illness. The bacteria are red, and the host cell is green.

April 22, 2021

Researchers have found the mechanism that one bacterium uses to enter the intestinal cells of the body. This bacterium is the most common cause of food-borne illness in the U.S.

The bacterium, Campylobacter jejuni, is contracted from eating raw or undercooked poultry, most often found in chicken, said Nick Negretti, WSU alumnus and postdoctoral research fellow at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

C. jejuni is similar to salmonella. People infected with it tend to get severe abdominal cramps and can have a fever, Negretti said.

The researchers have discovered many secreted proteins that come from C. jejuni. One of them is called CiaD, which allows the bacterium to get into intestinal cells, said Michael Konkel, professor in the WSU School of Molecular Biosciences.

Researchers in the Konkel lab, which included Negretti, collaborated with researchers from the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory in Richland, Washington, to fully understand the mechanism of the protein, Konkel said.

When C. jejuni infects the body, the body creates antibodies that fight off the infection, Negretti said.

The antibodies sometimes turn and attack the healthy cells in the body, he said. When this occurs, this can lead to an increased risk of certain autoimmune disorders like post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome and reactive arthritis.

“They’re rare outcomes. They don’t happen all the time, but they happen,” Negretti said.

When the bacterium is treated by medical professionals, patients are usually prescribed a broad-spectrum antibiotic, Konkel said. These are antibiotics that fight a wide range of disease-causing bacteria, whereas narrow-spectrum antibiotics target only a few types of bacteria.

This bacterium, although rarely heard of, is much more prevalent than people think. The World Health Organization states that the bacterium is one of the top 10 threats because of antibiotic resistance, he said.

Bacteria that become resistant to antibiotics are much harder to treat and lead to higher medical costs and an increase in mortality rate, Negretti said. If they are resistant, antibiotics will no longer work, and unless other drugs are produced, there is no way to kill the bacteria.

Although the protein is only present in C. jejuni and not the closely related bacterium salmonella, it still offers insight into other bacteria’s infectious processes, Negretti said.

“The way it works is probably somewhat similar to other bacteria, which is why maybe it could be a target for drugs,” he said.

Because antibiotics are so widely used and antibiotic-resistant diseases are rising, it is important to look toward other mechanisms to fight off infections, Negretti said.

“The idea is that if [researchers] can understand what sort of tools these bacteria use to cause a disease, if we understand how those work, it may be possible to target those tools, instead of trying to kill the bacteria,” he said.

However, consumers can avoid C. jejuni with good cooking habits. People commonly ingest C. jejuni on foods that are cross-contaminated with raw chicken, undercooked chicken or unpasteurized milk, Negretti said.

The bacterium can easily be avoided using proper food safety. About 80 percent of the chicken bought at grocery stores contains C. jejuni, but when cooked properly, it is perfectly safe, he said.