Better by nature’s design

Natural wonders inspire biomimetic human inventions like swimsuits and robots

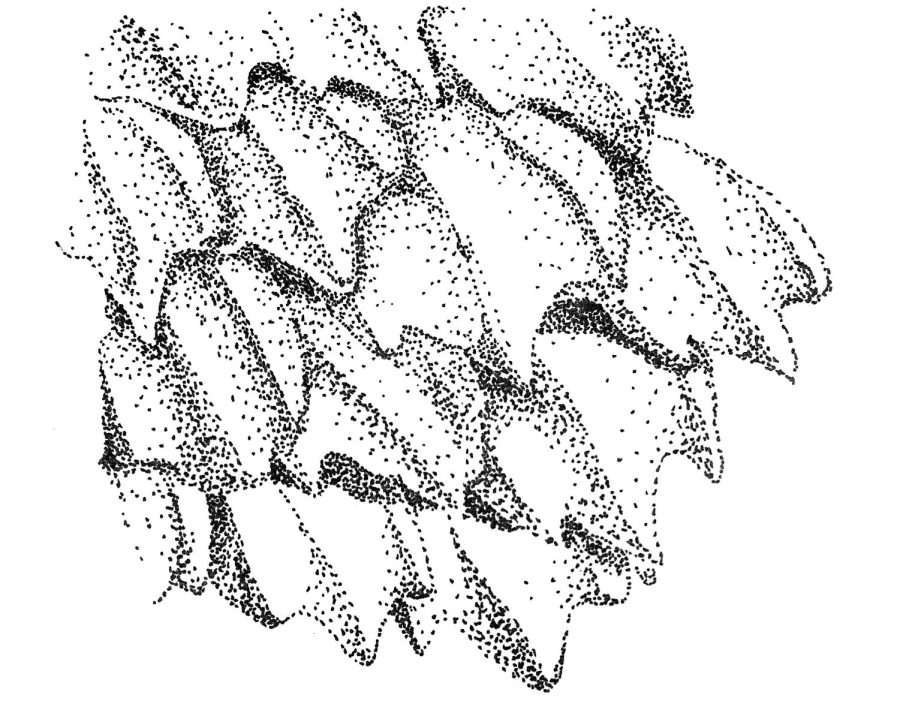

The denticles, or placoid scales, covering shark skin are easier to see under a scanning electron microscope.

February 24, 2022

It is a good thing nature does not believe in copyright. Designs inspired by nature are found throughout the world. From architecture to medicine, biomimicry is a technique humans are working to master.

Nature has perfected its designs through millions of years of mutation, natural selection and evolution. Oftentimes, humans work to invent something new only to end up finding it designed better by nature. Now, scientists and inventors in the field of biomimetics tend to look to nature for inspiration.

The most famous example of biomimicry is Velcro. During a walk with his dog in 1941, Swiss electrical engineer George de Mestral noticed the burrs tangled in his pet’s fur, according to Velcro’s website. The hook and loop structure of the burrs intrigued him and inspired him to invent Velcro.

Gecko gripping adaptation has also fascinated scientists. Their toes are covered in tiny, hair-like protrusions that allow them to grip onto vertical surfaces. By mimicking their toe pads, Stanford engineers created a set of hand-sized pads that allow a person to climb on smooth vertical surfaces like glass, according to Stanford University.

Gecko toes also inspired Stanford’s Stickybot III robot.

Robotics is perhaps the most nature-dependent field for inspiration. WSU researchers have created robots mimicking bees, earthworms, and other insects. Néstor O. Pérez-Arancibia, associate professor in Mechanical and Materials Engineering at WSU Pullman, designed Robeetle, setting the world record last year for smallest crawling robot, according to WSU Insider.

RoboBees, designed by Harvard roboticists, have applications in search and rescue, according to Harvard University.

Researchers in Singapore created MantaDroid, a robot that looks like a manta ray, according to National University of Singapore. Its appearance helps to camouflage it for underwater surveillance and biodiversity research.

Another surface that snags scientists’ attention is sharkskin. Sharkskin is covered in denticles, minuscule scales that lend antibacterial properties, according to Biomimicry Institute. The rough, pointed edges of the denticles stress the cellular membranes of bacteria and viruses, making it harder for them to survive.

One material mimicking the texture of sharkskin, called Sharklet, harbors 97% less Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) — an antibiotic-resistant superbug — bacteria than smooth surfaces, according to the Biomimicry Institute.

Denticles also reduce turbulence. Counterintuitively, their rough surface is more hydrodynamic than a smooth one. The denticles prevent tiny eddies from forming along the skin, reducing drag and improving thrust underwater, according to research conducted at Harvard University. Speedo designed fabric mimicking shark skin for its LZR Racer swimsuits.

In the 2008 Beijing Olympics, the U.S. swim team was outfitted with Speedo’s specialized suits, which were banned the following year for the unfair advantage they gave wearers. Recent research has revealed the now-infamous swimwear did not improve speed due to its biomimetic surface, according to Harvard researchers. Instead, the suits’ compression and streamlining properties were the key factors at play.

Besides Speedo’s designs, many other fabrics mimic nature. MIT researchers studied the water repellent properties of lotus leaves to produce waterproof fabrics.

Some fabrics and paints have even replicated the structures present in iridescent butterfly wings to produce beautiful, vivid colors without dyes, according to Scientific American.

Aerodynamics is yet another area of science where biomimicry is in the spotlight. Japanese bullet trains depend on aerodynamics to slice through the air in the most efficient way possible. However, the debut of the Shinkansen II came with a problem: noise!

To reduce the booms the fast-moving train was producing as it exited tunnels, Japanese scientists took inspiration from the sleek bill of the kingfisher. The shape of the bird’s bill allows it to enter the water with virtually no splash as it dives for fish. It did wonders for the bullet train, too. Shaping the front of the train like the kingfisher’s bill reduced air resistance by 30%, eliminating the booms, increasing speed and reducing energy usage, according to BBC.

Biomimetics comes on a large scale, too, especially in energy-efficient architecture. Termites are some of nature’s busiest construction workers and scientists were smart to look to them for the answer.

Turns out, termites have a clever way to keep themselves cool. By building strategic air pockets into their mounds, termites utilize natural convection that keeps their mounds ventilated and cool, according to National Geographic. One mall in Zimbabwe utilizes this technique, using 90% less energy than neighboring buildings that rely on traditional air-conditioning.

From clothes to transportation and everything in between, biomimetics inspires new inventions and improves existing designs. Biomimicry simplifies our daily lives and decreases our impacts on the planet. Take a second glance at the designs around you and give nature some credit where it is due.