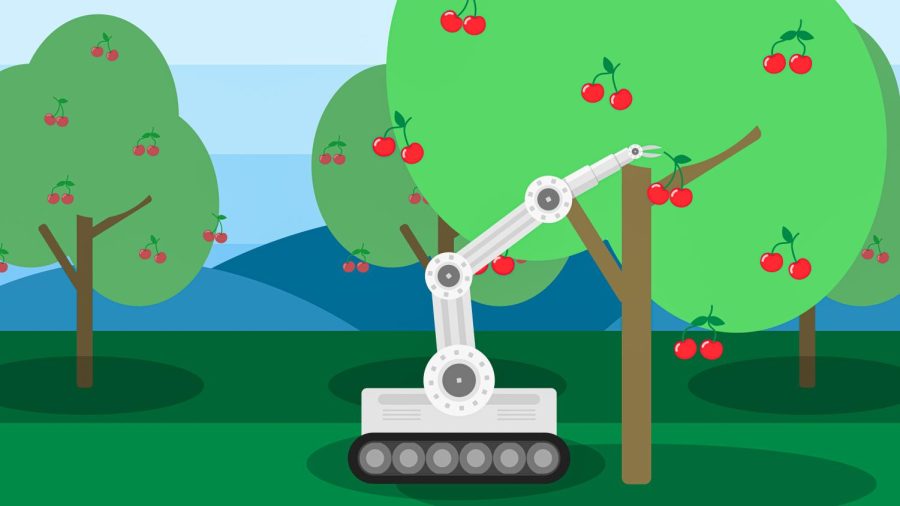

Research aims to replace human pruners with robots

Current field tests successful; further development needed

The initial strategy for the co-operative pruning process is to have robots prune 80% of the tree.

April 7, 2022

Researchers are developing a robotic system for pruning. The system will allow human pruners and robots to coexist in the same environment.

Pruning is a process used to manage the annual growth of trees and the balance of quality fruit. The process depends on factors like the type of branches and fruit, said Matthew Whiting, professor at the Department of Horticulture.

A current problem with pruning is the limitation of human pruners. Pruning takes place during the winter when conditions are cold and harsh, and it must be completed before new growth to ensure a quality harvest. The labor demographic of pruning is also aging, decreasing the number of available pruners, Whiting said.

“The fact of the matter is there may not be [many] people left in Washington state who want to prune in the middle of the winter and have the skill, history and the experience to prune,” he said. “The demographics are changing and we need to mechanize the processes.”

The goal of the project is to gain a better understanding of pruning through a co-robotic system. The system will replace human pruners and create a consistent pruning process, Whiting said.

Whiting said he hypothesizes robotic systems will relieve humans from working in harsh conditions. It will also increase the efficiency of pruning.

“One of the interesting prospects of having a robotic pruning system is that it will do the same thing every time,” he said. “We think there is the potential also, in the long run, to improve the consistency in pruning decisions in orchards and that that could lead to better quality fruit in the long run.”

Research and development of co-robotic systems are divided into three areas, said Manoj Karkee, associate professor at the Center for Precision & Automated Agricultural Systems.

The first area of focus is understanding pruning decisions. Pruners are observed while working to determine pruning decisions through a camera and vision system. The robotic system collects images and videos to analyze and compare. The collaborative effort will allow researchers to determine pruning rules, strategies and techniques, Karkee said.

The second area of focus is the integration of information into the control system. The project will use a rotational arm system, which has rotational joints that behave similarly to human joints in the arm, he said.

Other joints also allow the mechanical arm system to move. However, these joints are limited through linear movement and are expensive to install, Karkee said.

AI techniques will create a three-dimensional environment using information from the machine vision system. The system will recreate the environment to identify objects. From the given information, the location of the object is sent to the control system to activate the robotic arm, he said.

“[The system] recreates the trees in three dimensions so that we can find out or estimate the diameter, length, spacing between branches and other geometric and color parameters of these trees and branches,” Karkee said.

The final focus of the project is testing the robotic and vision systems both inside the lab and in the field. The initial strategy is to have the robotic system prune about 80% of the tree. Human pruners will prune the remaining 20%, he said.

One drawback of the co-robotic system is the potential risk of human harm due to malfunction in robots. Physically separating humans and robots can reduce the risk of harm, he said.

The robotic system was field-tested in March, with the system successful in pruning a few branches. Further development is necessary before the system is tested again, Karkee said.