Mutated mice improve understanding of heart disease

Heart disease occurs once in every 200 people

April 7, 2022

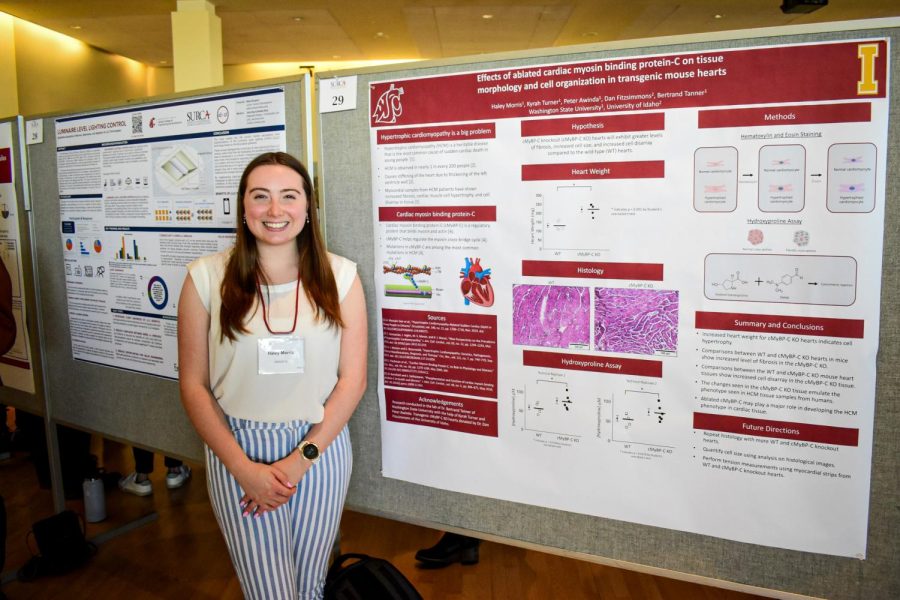

WSU undergraduate researcher Haley Morris uses mice as a model to study a heart disease present in nearly one in 200 people — hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

HCM is a heritable condition where the walls of the heart thicken, which causes the heart to stiffen and reduce blood flow. In hearts with HCM, the cells are less organized, and there is more scarring between them, which may contribute to the thickening of the heart wall.

Morris, senior biochemistry major, investigated the role of a specific protein called cardiac myosin binding protein-C (cMyBP-C) in the development of HCM-like symptoms. Mutations in cMyBP-C are some of the most common causes of HCM, making them important for better understanding the disease.

This essential protein is involved in the regulation of heart cell function, so hearts lacking it could be prone to HCM.

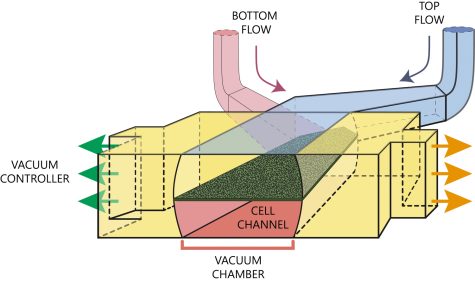

To test this theory, Morris stained the cells in mice hearts without cMyBP-C. Cells affected by HCM are larger and less organized than normal, making them quite distinct looking.

Morris and colleagues measured the level of scarring around cells with a technique called a hydroxyproline assay. A chemical treatment causes a component of the scar tissue to change color, allowing Morris to measure the color change and the proportional scarring.

Morris found that hearts lacking cMyBP-C had increased scarring, decreased cell organization and were heavier than normal hearts, indicating this protein contributes to HCM symptoms.

In the future, Morris said she hopes to measure heart cell size to see if cells are larger in HCM hearts.

Bioengineering professor Bertrand Tanner mentored Morris’s research, which was presented at the 2022 Showcase for Undergraduate Research and Creative Activities.

Jackie Edmonds is a senior microbiology major and wrote this article for her senior capstone course.