Cougar Cage sets stage for researchers to reduce plastic waste

Researchers win funding from Cougar Cage, will eventually break down polylactic acid for 3D printable resin

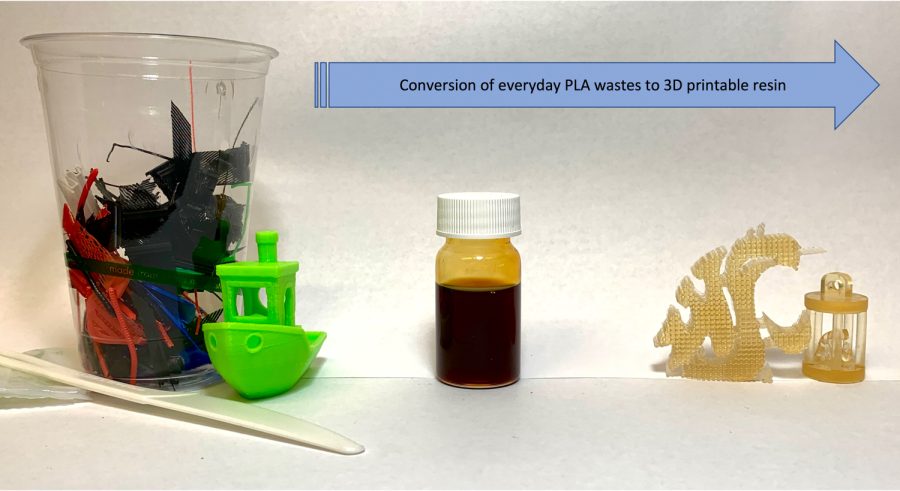

Everyday polylactic acid wastes can be chemically broken down into monomers and then transformed into 3D printable resin within 48 hours.

July 14, 2022

Post-doctoral research associate Yu-Chung Chang and his team won $50,000 to explore chemical recycling on May 10 at Cougar Cage, hoping to reduce plastic waste in landfills and oceans.

Cougar Cage is an event, like “Shark Tank,” where researchers pitch their project to a panel of judges, who determine if it will benefit the environment and humanity. Researchers also explain how funding can further propel their project, Chang said.

“There are a bunch of competitors from [WSU] Vancouver, Spokane and Pullman campuses,” Chang said. “[Each group] has a researcher come in to compete and present [their] idea. It is a very diverse competition to see whose ideas can shine among each other.”

Cougar Cage is open to students, clubs, professors and anyone at WSU who wants to present their idea. The only requirements are projects must be meaningful, impactful and have good marketability, he said.

In the first two rounds of the event, participants submitted a proposal to the WSU Foundation and prepared a Zoom presentation for the corporate vice president and WSU President Kirk Schulz, Chang said.

In round three, judges sent Chang and five other researchers to compete in Seattle, where they presented their proposal to a group of judges at the Brighton Jones office. The judges included the foundation, Schulz and the Palouse Club, which consists of investors and philanthropists. Judges selected Chang and two other participants to receive funding, he said.

Chang said the event was intense and exciting. He encourages people to enroll and join by submitting their proposals to the WSU Foundation via email.

“I encourage people to enroll and join if they have a great idea and do not fund student engineering clubs, science clubs, or art clubs,” Chang said. “Everybody is welcome [and] if you have something good to pitch, I recommend people give it a shot.”

Chang presented the concept of chemical recycling as an alternative to traditional recycling methods, said Jinwen Zhang, professor for the School of Mechanical and Material Engineering.

“[In] chemical recycling, we also deem it upcycling. We break down the molecule structure into small molecules and rebuild a new polymer material from the small molecules,” Zhang said.

Zhang said he and Chang are working alongside Lin Shao, a post-doctoral student in the Material Sciences and Engineering program. The project focuses on the chemical process of depolymerization. The process breaks down polylactic acid and other polymers into monomers or small molecules.

PLA is a cornstarch-based plastic that is biodegradable and compostable, though Zhang said most PLA plastics are incinerated or landfilled after use.

“If you dump [PLA plastics] in a landfill, it could take a long time for them to degrade compared to a water bottle,” Chang said. “The fact that it is biodegradable does not mean we should just toss it out randomly. That is how this project came to be.”

Chang said traditional recycling methods are energy-intensive and have a limit. The process also weakens PLA plastic, whereas chemical recycling can break down and rebuild it into a new plastic that is stronger.

“The reason we started with PLA plastics is [because] it is a rising bioplastic derived from cornstarch and sugar, and these are valuable food sources,” he said. “We do not want to turn it into plastic, use it and then toss it away as that is not economically viable. We will make it into something more valuable.”

The goal is to offer an alternative method of traditional recycling that is sustainable and economical. The recycling method is also applicable to other polyesters, Zhang said.

“What we have learned from this project is [PLA] applies to other polyesters,” he said. ”[Our knowledge] is generally applied to manage similar polyester-type polymers. We set up a new framework for depolymerization of the polyesters.”

Shao said plastic accumulation is a problem, and chemical recycling can address this issue.

“In our daily lives, we produce a lot of plastic waste, [which] ends up in the ocean,” Shao said. “We want to produce this project to recycle the plastic because [we produce] a large amount of plastic.”

Researchers will collect PLA waste and break it down into monomers, or molecules, for 3D printing. The monomers are transformed into 3D printable resin, or a liquid monomer, and exposed to wavelengths of light to solidify the resin. Chang said the process allows researchers to create any shape they want.

Chemical recycling is a very mild process in which the researchers expose the polymers to 100 degrees Celsius for an hour. The chemical process completely decomposes the polymer into small monomers. Researchers can then rebuild the molecule into a photocurable resin, which has mechanical and thermal properties. It is better than some commercial resins, Shao said.

“We want to optimize this material further into something applicable,” Chang said. “We create a material and think it is good, but we must find a suitable application. 3D printing is always a good choice because you can create whatever you want with it, and we want to provide an alternative and superior material in this case.”

The project is in the post-beginning stage and will last a few more years. Zhang hopes to receive interest and funding to extend the project.