Fatty acid-induced cell death may fight cancer

WSU researchers investigate DGLA, causes of ferroptosis

DGLA could cause nematodes to become infertile.

September 16, 2022

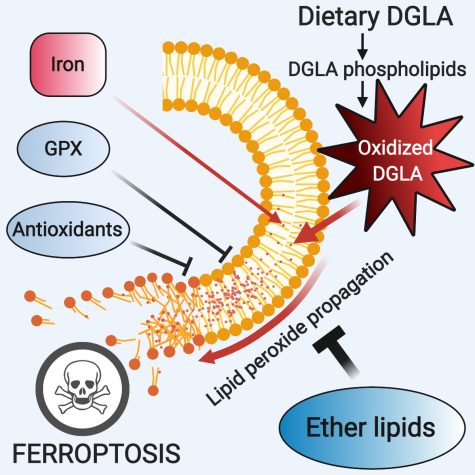

Researchers at WSU seek to better understand the mechanisms of ferroptosis, a programmed cell death process dependent on iron, and how it can be triggered by polyunsaturated fatty acids.

The fatty acid-induced cell death was found to kill cancer cells and has promising therapeutic potential, said Jennifer Watts, professor in molecular biosciences.

“If we could figure out how to induce [ferroptosis], and we could target this inducer to a tumor, then you can fight cancer that way,” Watts said.

The fatty acid they studied, dihomo-γ-linolenic acid (DGLA), is only found in trace amounts in human diets, she said. The amount of DGLA that people might consume should not be enough to trigger ferroptosis.

The researchers are investigating the mechanisms and enzymes involved with causing ferroptosis, Watts said.

“What’s so striking, I think, about our finding is it’s not just any of those polyunsaturated fats, it’s really this one [DGLA],” she said.

The enzymes could convert DGLA in the cell membrane into an oxygenated form, she said. This oxygenated form could be responsible for spreading radicals, highly reactive molecules, throughout the lipid bilayer, the double layer of fats, that hold the cell together.

These radicals disrupt the bilayer by oxidizing its double bonds, starting a chain reaction of lipids forming bonds with adjacent lipids, said Marcos Perez, postdoctoral research associate.

This chain reaction eventually disrupts the structure of the membrane, killing the cell and completing the process of ferroptosis, Perez said.

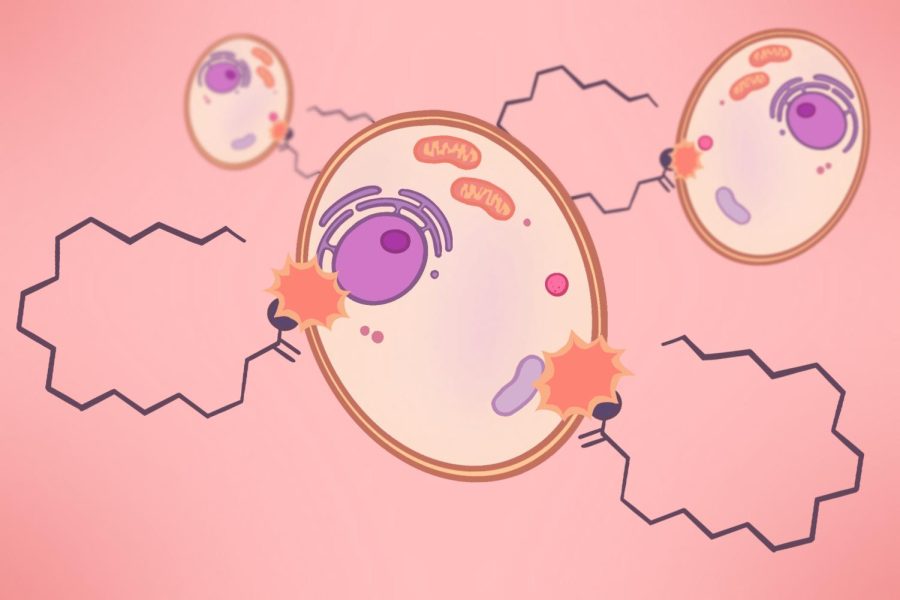

DGLA moves along its pathway, causing ferroptosis.

The enzyme involved in oxygenating the DGLA likely uses an iron molecule to propagate the radicals, characteristic of ferroptosis, Watts said.

“It has to do with the different forms of iron reacting with the radicals,” she said. ”but it can lead to more and more radical formation.”

In an experiment in 2020, nematodes that were consistently fed more DGLA became infertile as their germ-line cells began to die, according to a paper written by Perez and Watts. The researchers ruled out normal apoptosis, a typical programmed cell death, by knocking out genes responsible for causing apoptosis.

Another finding was there are specific inhibitors that are protecting cells from ferroptosis, according to the paper.

“There were certain genes that were protective, or that were proactively causing ferroptosis,” Perez said.

There is also developing evidence that ferroptosis could be the cause of neurodegenerative diseases, or dementia, Watts said.

“Ferroptosis also occurs in tissues that have fats … that brain has a lot of fatty acids in the tissue. It’s a very lipid-rich organ and so you don’t want that kind of cell death occurring there,” Perez said.

The researchers also understand the mechanism by using nematodes as a model because they are simple, small organisms, Watts said.

“It only has 989 somatic cells, so like 300 neurons, which is very small … so people can actually study cellular connections and patterns of development,” she said.