Lawmakers should be held accountable for new budget

WSU Capital Budget Director Deborah Carlson explains the two-year state capital budget cycle. This budget is responsible for appropriating funds from the state for construction projects and renovations on campus.

MATT ESTABROOK | THE DAILY EVERGREEN

Capital Budget Director, Deborah Carlson, explains the two-year state capital budget cycle Thursday in the French Administration Building. This budget is responsible for appropriating funds from the state for construction projects and renovations on campus.

February 13, 2018

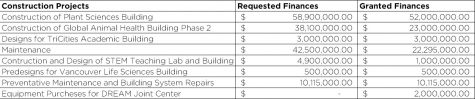

In late January, the state Legislature approved the capital budget for Washington, granting money to a variety of organizations to design and build new facilities. Among the approved grants, $114 million was appropriated to WSU for facility upgrades and repairs.

Many students were critical of WSU administration for this, asking questions like, “If we can get $114 million for new buildings, why can’t we fund Performing Arts?” The short of it is that money from the capital budget can only be used for projects like new buildings and tangible investments, not university programs or staff salaries.

“When somebody’s mad because we’re building a building instead of putting that money back in a program that had to be cut,” WSU Capital Budget Director Deborah Carlson said, “we don’t really have a choice.”

Washington divides the budget into two parts, capital and operations. Capital is for infrastructure projects and is paid in one-time chunks. The operations budget is ongoing and includes funding that goes toward staff salaries, programs and maintenance.

When presented with extreme cuts to the Multicultural Student Services and Performing Arts, it is easy to jump to the assumption that WSU is comfortable cutting programs in favor of new academic facilities. This budget system, while designed to separate out different projects based on priority, has a major feature that students ought to consider: Every university competes for a cut from the same pool of education money.

State lawmakers will rank each proposed project against one another based on its merit. A project that is the first priority to one school might be deemed a lower priority than a project at another school. Funding can often be distributed in a way that overlooks the demand for certain projects in favor of managing costs.

Technical and community colleges, on the other hand, are all grouped into one capital budget request. This makes their priority list easier to manage for the state because they can rank the highest priority project for the whole group of schools. These colleges are more likely to get funding that reflects their values than WSU or University of Washington.

“The scoring process isn’t always reflected in the end result,” Carlson said. “Once the Legislature starts and you have different areas of the state with different support groups or legislative clout, sometimes we end up with projects we didn’t ask for. Sometimes they honor our priority lists and sometimes they don’t.”

Blaming administration seems like the obvious solution, but there are forces beyond their control that deserve more scrutiny. Lawmakers, not administration, actually decide how much money every college in Washington gets. In the current budget, only $22 million has been granted to WSU for repairs despite there being a tremendous need for upkeep.

A breakdown of the 2017-2019 capital budget request and funds granted by the state. WSU competes with other schools for project priority.

“Our backlog for [maintenance] is over $750 million,” Carlson said. “If we were to fix everything that needed fixing, not just the big emergencies and the really, really top echelon, we would need a lot more money than $22 million.”

Ten years ago, the state moved $10 million from WSU’s operations budget to the capital budget. This prevented those funds from being used for construction and renovation.

Carlson said this cut didn’t really impact the university in terms of how the campus runs. It makes it seem like the capital budget is larger than it really is, meaning it is less likely for additional capital funds to be appropriated to WSU.

While it may not make a difference in terms of people getting paid, where our money comes from matters. Education shouldn’t be a commodity people have to compete over. The administration may seem like the boogeyman, but the real problem is state politics.

The people who ought to be criticized and petitioned are lawmakers. Universities shouldn’t have to compete for funds in order to fix their buildings or pay for programs that serve so many students on their campus.

We should always expect more from our leaders, but that expectation should be tempered with empathy when change is out of their control. Be critical, be demanding, but also be smart enough to recognize when demands are falling on empty accounts and not deaf ears.