Athletics accounts for half decrease in reserves

Sports’ disproportionate draw on savings raises questions of WSU’s priorities

TEVA MAYER | The Daily Evergreen

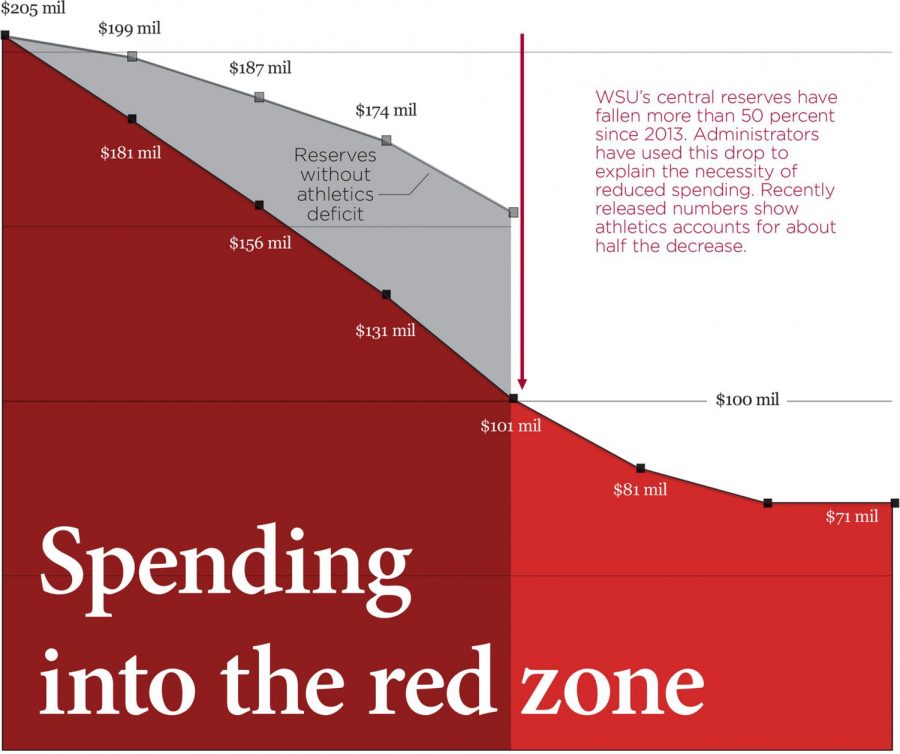

The starting reserve balance of $205 million in 2013 comes from a chart WSU published in the fall. Deficits for the university and for athletics come from the Budget Office. The athletics deficits differ slightly from those previously reported, and the Budget Office could not immediately explain the discrepancy.

April 4, 2018

Newly released financial figures show WSU Athletics accounts for roughly half the drop in university savings, which administrators have used to justify system-wide spending cuts of 2.5 percent.

Officials have traditionally said the athletics budget is separate from the university’s, and that athletics does not take money from academics or vice versa. But once athletics began overspending its own budget, it dipped into WSU’s general savings, draining about $50 million since 2013 and contributing to a precarious financial situation.

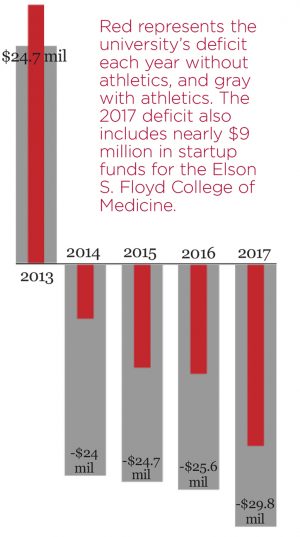

The athletics deficit of the past five years is nearly four times larger than the cumulative deficit of all WSU colleges and academic units combined, excluding the new Elson S. Floyd College of Medicine, according to data provided by the WSU Budget Office.

This reflects a nationwide tension between athletics and academics. Universities — including WSU — insist robust sports programs boost their appeal. WSU President Kirk Schulz has called athletics the “front door of the university.” But some argue these priorities are misguided.

“Universities exist for a reason: for higher learning,” said David Ridpath, a sports administration professor at Ohio University and member of the Drake Group, which advocates for an overhaul of commercialized college sports.

“It’s not about elite sport development,” he added, “or our entertainment, or coaches getting paid millions of dollars.”

As at WSU, overspending on sports often carves a deep debt, with the consequences extending beyond athletics. Schulz’s plan to curb the overall drop in central reserves has resulted in the elimination of the Performing Arts program and a near-total hiring freeze across all areas of the university.

Based on the figures provided by the Budget Office.

Spending reductions also threatened to cut several multicultural retention counselor positions and part of some graduate students’ stipends, but administrators reversed the decisions amid student outrage.

Though athletics has implemented its own spending plan like the rest of the university, many feel the department receives preferential treatment. Faculty Senate Chair Judi McDonald said as much at a Senate meeting earlier this month, while discussing home football game parking lot closures.

“Athletics gets what athletics wants,” she said, “and the rest of us suffer.”

The value of reputation

One of the main arguments for high-spending college sports programs is that the better the teams — primarily football — the more prestige they bring to a university. This is widely thought to lead to an increase in applications, donations and other hard-to-measure benefits.

Administrators use this reasoning to show the importance of staying competitive in athletics. It surely helps with brand recognition, as anyone can watch WSU sports on TV. Some studies have even shown a spike in enrollment for a year or two after a major football or basketball victory, with others finding little correlation.

But Ridpath, the sports administration expert, said it is also important to weigh the odds of, say, winning a bowl game against the investment needed to do so. If WSU plays well enough every other year, it may be worth it; if only once a decade, it may not.

“There’s only going to be one winner and a lot of losers,” Ridpath said. “How often can WSU win the outright title?”

Competitiveness is a tall order. College sports programs are engaged in what is commonly referred to as an “arms race” to build the most lavish facilities, hire the most effective coaches and thereby recruit the most impressive athletes.

WSU spokesman Phil Weiler agreed administrators nationwide are struggling to decide the role sports should play in a public university.

“Every college president in America that has athletics is asking herself or himself that question,” Weiler said.

Schulz’s main priority since arriving at WSU two years ago has been to transform the university into a premiere research institution. His flagship “Drive to 25” campaign aims to push WSU into the highest echelons of research by 2030.

Ridpath said top-notch sports teams are not essential to this mission. He has argued in The Washington Post that it is wrong for colleges to support athletics deficits at the expense of students and academics.

“If Washington State’s going to be a top-25 university,” he said, “athletics isn’t going to matter.”

Weiler noted that WSU pursues many goals at once, and that high-quality sports teams and academics are not mutually exclusive.

However, athletics represented more than half of the university’s overall deficit every year from 2014 to 2016. In 2017, startup costs for the Elson S. Floyd College of Medicine accounted for about a third of the overspending, and athletics spending for another third.

Stacy Pearson, vice president for finance and administration, acknowledged this results in a slower recovery time for the university as a whole. Each unit must restrict hiring even as WSU strives for research excellence, and those with surpluses are not allowed to spend them.

But for many, sports are closely tied to overall college enjoyment. Weiler recalled talking to a student at one of his former universities who explained she had never been a football fan, but the shared experience of attending home games was an integral part of her college experience.

A. G. Rud, a former Faculty Senate chair, said he researches college athletics informally. He agreed the state of athletics spending is concerning, but that nevertheless, sports are an important part of American universities.

“I do like the fact that we’re trying to pursue athletic excellence,” he said. “If you’re going to do big-time athletics, you have to do your best.”

The cost of competition

Perhaps the most obvious and controversial expenses in college athletics are the salaries. After a $1-million raise, football Head Coach Mike Leach is set to make $4 million in 2020 and is one of the highest-paid state employees in Washington, second only to University of Washington football Head Coach Chris Petersen.

The issue has arisen at Faculty Senate meetings repeatedly. While coaches’ salaries grow uncapped, Rud said, faculty have been lucky to see a 1-percent raise.

“We have … professors who have been here for many years, who work hard and teach hard and do research,” he noted. “They make a fraction of what the football coach makes.”

But the largest slice of the athletics deficit came from facility debts. When former Athletics Director Bill Moos arrived in Pullman in 2010, he and late President Elson S. Floyd developed a plan to revive a loss-ridden football team.

After hiring Leach and men’s basketball Head Coach Ernie Kent, who earns $1.4 million per year, Moos and Floyd spent $65 million on renovations to Martin Stadium, and $61 million on a new football complex.

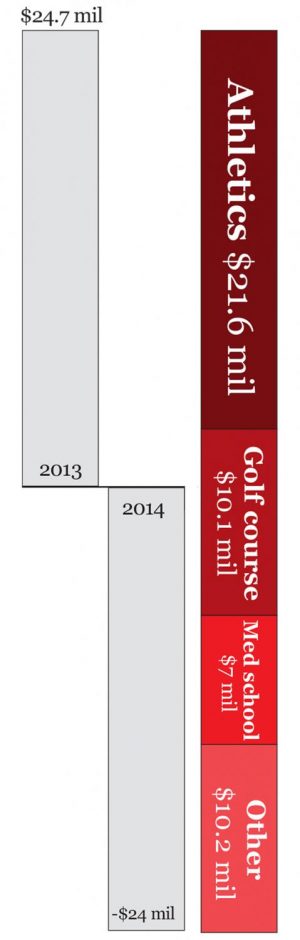

Various athletics debts account for nearly half the 2013-2014 swing into WSU’s deficit spending, shown in the two left bars.

But then athletics received less in Pac-12 distribution revenue and institutional support from WSU than expected, leaving the program unable to cover the cost of the building projects. In its 2014 deficit of about $13 million, facilities accounted for about $9 million.

Athletics also pays millions each in student aid and team travel, as well as equipment, uniforms and supplies, among other things. Rud said it all boils down to offering an attractive package to student athletes.

“There’s a lot of that going on,” he said. “It’s sold to people as ‘We need to attract these 18-year-olds that can throw a ball or make a tackle.’ ”

Weiler said it is essential to have the best of everything to offer student athletes — and fans — the best experience possible. But he acknowledged that doesn’t mean the system is functioning properly.

“It’s not sustainable,” he said. “No one thinks it is.”

Put simply, athletics must spend less money and generate more. As a university far from population centers, WSU has a challenging time bringing in home-game revenue, one major funding source. It’s harder for people to get here, and Martin Stadium is the smallest in the Pac-12, limiting ticket sales.

Additionally, Weiler said fans and alumni aren’t donating as much as those at peer institutions, and WSU athletics has one of the smallest budgets in the Power Five, the country’s big-time sports conferences.

“They do have a lot of challenges,” Pearson said, “but they also have a lot of opportunities.”

The path to profit

Under new Athletics Director Patrick Chun, WSU is focused on revenue. Schulz has touted Chun’s fundraising prowess as one of the main reasons for offering him the position, and his history at Florida Atlantic University seems to support the claim.

Most notably, during his tenure in 2015, the school received its largest-ever donation: a $16-million gift for an athletics complex. One of WSU’s highest athletic priorities is to build an indoor practice facility, to give all teams a climate-controlled building for practices.

The Seattle Times reported shortly after Chun’s hiring that he had already traveled to Seattle to meet with constituents, and that he planned to keep it up.

Weiler agreed the university has not maximized fundraising. WSU has loyal fans, he said, but its athletics department is at the bottom end of the Pac-12 in donations.

However, Chun said he believes athletics’ overspending has set the program up for success, which will hypothetically lead to an increase in giving. He added that WSU’s brand is the strongest it’s ever been.

“We’re in a great position,” Chun said, “because of all the investments that were made here in the past.”

In the past five years, WSU has played in four bowl games, after a decade without one. Contributions are on the rise, and ticket sales reached a high in 2017, according to NCAA financial reports.

Other aspects of the spending plan athletics developed in 2016, however, have not panned out.

Schulz and Moos proposed an athletics fee of $100 per year to the Board of Regents in September 2016, but after strong opposition from students, the fee never went to a vote.

They again went to ASWSU in February, this time to propose a mandatory $265 student sports pass fee. This would have increased sports pass revenue from $2.7 million to $4.3 million. The Senate voted not to include it on the election ballot.

Without the proposed fees, WSU students paid about $40 each to athletics in Services and Activities fees this year, for a total of about $750,000 or 7.3 percent of total S&A fees. Part of another mandatory $1,250 in fees goes toward the Martin Stadium renovations, and optional undergraduate sports passes cost $239.

Another significant revenue was supposed to come from the sale of beer in Martin Stadium, but after trying unsuccessfully for more than a year to obtain a permit from the Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board, WSU stopped pursuing alcohol sales. This would have provided an estimated $600,000 per year.

But season ticket sales are on the rise, and Chun is confident Coug fans will open their wallets to help nudge the program back into the black.

The problem with this, according to Ridpath, is that prioritizing new revenue is a double-edged sword. To generate money in ticket sales and donations, the football team must continue to improve. This improvement implies more investing, and so on in an unending cycle.

“Any type of gain is typically offset by more stupid spending,” Ridpath said.

Instead, he recommended spending less, comparing it to what the average person would likely do to save money.

The only spending reductions athletics has publicly announced are leaving some positions vacant and “overall belt tightening.” Chun said he believes it is important to be “great stewards of our resources.” But if a program is going to remain competitive, there are no obvious areas to cut from.

“If there was an easy answer,” Weiler said, “this wouldn’t be an issue that people are grappling with across the country.”

Difficult answers

Some universities, struggling to stay afloat, have eliminated sports to cut costs. Ridpath said some have even done away with football. But this would not eliminate all the costs associated with athletics, like bond payments, Pearson said.

Besides, sports are still deeply important to many students, alumni and other fans.

“Cougs take great pride in what we do in the athletics field,” Chun said.

Other institutions, like the University of Idaho, have dropped to a lower division, realizing it did not have the resources to be competitive at the highest level of college football. Though many feel this implies sacrificing relevancy, Ridpath disagreed. He said it may be a good option for some universities.

Weiler said WSU could have this conversation to decide what is most important, but that it would need to include all invested groups, from students and alumni to faculty, staff and donors.

As Chun noted, the pride and tradition of Cougar athletics playing top-tier sports would likely outweigh any benefits in bowing out of the university’s current conference. He said he would not consider this, reiterating that he believes fans will be willing to help.

Pearson agreed joining a lower division would not appeal to the WSU community.

“I think that there would be a lot of heartburn over not being a Pac-12 school,” Pearson said.

She argues for a conservative approach, aimed at saving rather than making money. If WSU has a smaller budget than its peers, she said, that just means it must spend less than its peers.

“Bottom line,” she said, “focus on that expenditure reduction.”

The university has said athletics, like all other departments, will eventually have to repay its debts to WSU. But Pearson said it will likely take athletics longer to eliminate its deficit than other departments, and the foremost goal is to balance its budget.

In the meantime, athletics overspending ripples disproportionately through the rest of the university, impacting even departments that have managed their budgets well, as all areas reduce spending by 2.5 percent.

“I know a lot of things we put forward are not popular,” Pearson said, “but if I’m going to be responsible for the overall fiscal health of the university, I’ve got to get this number up to here.”

She pointed to the $100-million mark on the reserves chart. This would be 10 percent of the university’s overall budget, sufficient as a rainy day fund to cover costs related to incidents like the cybersecurity breach last spring, and to jumpstart strategic initiatives like the medical college.

She hopes to reach this point within three to five years of operating in recovery mode, she said, and reining in athletics spending is a key piece of that puzzle.

Chun noted that athletics spent less than it projected in 2017. However, Chief Financial Officer Matt Kleffner said this was due to one-time money from the NCAA.

Kleffner is unsure what deficit the program will post this year, saying he should have a better idea by early June. Athletics does not have scheduled spending reduction targets, he said but continuously revises its financial plan.

“It’s in flux,” he said.

Ridpath argues the overarching issue in college athletics is that it is poorly operated. The surest route to turning a profit is simply to spend less, he said. Pearson echoed this sentiment.

“It’s not without value,” she said. “It just needs to be managed.”

[pdf-embedder url=”https://dailyevergreen.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Run-Rate-History-by-Area-2013-2017.pdf” title=”Run Rate History by Area 2013-2017″]