Guest column: Use reservation in foreign intervention

COURTESY OF MIGRATION POLICY INSTITUTE

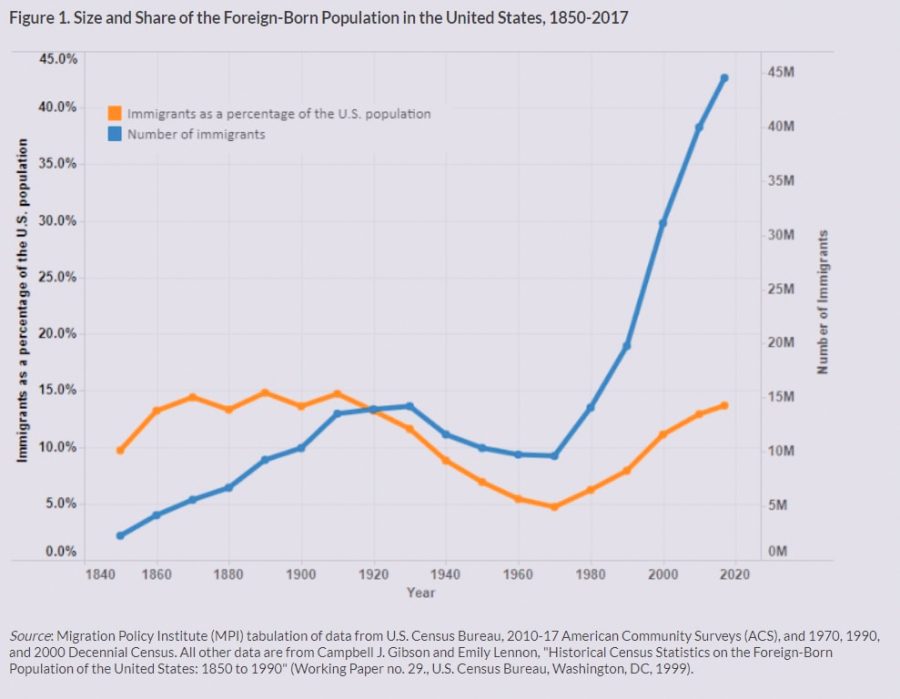

Mass immigration into the U.S. from South America can be attributed to U.S. foreign intervention, raising the question of what repercussions future intervention could have.

March 21, 2019

Tensions have been growing between the United States and Venezuela since Nicolas Maduro won reelection in a flawed election process in May 2018.

The subsequent reaction by the United States has been highly reminiscent of Cold War-era policies. For readers who did not live through the Cold War, the United States was plunged into fear that after the Second World War, communism would spread from the Soviet Union and destabilize the West. This fear led to almost a half-century of geopolitical tensions between the two superpowers that involved political and military interventions and struggles across the world, with fears by many that it would lead to nuclear war.

In recent history, the right has never passed up an opportunity to mock Venezuela for their socialist government, first under Hugo Chávez since 1998, and Nicolas Maduro since Chávez’s death in 2013. Venezuela’s perceived failures have been touted as an example of what happens when a country turns to socialism and a lesson for the ’uninformed’ youth who propose socialist policies for the United States.

This constant attack on Venezuela has created a climate where even many on the left, who were opposed to the U.S. intervention in Iraq in 2003, suddenly accept the need of military intervention and regime change for “humanitarian reasons.” All we need are shoes being thrown at the president, and the time lapse will be complete.

Unfortunately, there is a significant problem for those who propose intervention; the U.S. has engaged in intervention since the adoption of the Monroe doctrine in 1823 without much positive outcome. American policy towards Latin America has clearly played into the circumstances around our current immigration issues.

In 1904, President Theodore Roosevelt declared that the United States could “exercise international police power,” in order to ensure that nations in the Western Hemisphere kept in line with their commitments to international creditors to prevent a European invasion of Venezuela. While this did not affect relations between the Americas and Europe, it did provide justification for American interventions in Cuba, Nicaragua, Haiti and the Dominican Republic. These interventions have left both internal destruction, displacement, and the migration crisis that we see today.

Over the last few decades, military and economic interventions have undermined the economies and stability of the entire region which in turn has created power vacuums filled by drug cartels and military alliances. Recently, CAFTA-DR, a trade agreement between the United States the Dominican Republic, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Honduras has forced these countries to become economically dependent on the United States through increasing American agricultural products that weakens the domestic businesses.

All of these policies have led to the destabilization of Latin America and mass immigration to the United States. And yet, while the administration is combating this immigrant crisis at our southern borders (created largely by our own foreign policies), we are seeking to intervene yet again in a sovereign country.

The danger of the current administration returning to an antiquated foreign policy, the ramifications of which we are still dealing with, should give us pause to consider the consequences of “humanitarian intervention.”

Some may argue that correlation is not causation and that the interventions in Latin America did not cause destabilization. Rather, the argument is that those countries were already in crisis and that intervention did not cause further destabilization. While it is just a correlation, it is an unusually strong correlation given the timing of repeated spikes in mass immigration from South America to the United States following military interventions.

One merely has to look at a brief history of United States interventions to observe the correlation. In 1964 the United States backed a coup d’état by right-wing authoritarians against socialist Joao Goulart in Brazil. This coup was meant to prevent “Brazil from becoming another Cuba,” according to President John F. Kennedy. The following decades resulted in extreme poverty and violence in Brazil.

In 1970, then president Richard Nixon began an economic war against Chile and their democratically elected president, Salvador Allende, culminating in a 1973 coup d’état backed by the CIA. For the next 16 years Chile was governed by a U.S. backed military dictatorship that tortured thousands of political opponents and committed other human rights abuses.

The United States also supported the military dictatorship in Uruguay after a military-led coup d’état in 1973 and following dictatorship of Juan Maria Bordaberry. During his dictatorship, trade union leaders and political opponents were killed, arrested, or exiled.

The combination of military interventions during the Cold War and the undermining of economies in Latin America to impose dependence on the United States has led to economic disparity, political repression, and violence that has driven people from their homes in search of safety and opportunity. Many fled north because their political beliefs and motivations endangered them of imprisonment or death. Thousands of others migrated because of economic inequality where land, jobs and other resources were forcefully concentrated into the oligarchy.

The United States, in an effort to leverage the global economy, strong-armed Latin American governments into reducing state regulation in order to create opportunities for foreign companies. These economic regulation changes created thousands of low-wage jobs but at the expense of social programs like hospitals, schools, and labor protection.

Without the most basic of social safety-net programs, people migrated north, leading to a massive spike in immigrants coming into the United States. There is a clear correlation between the start of interventions in the late 1960s and the migration increase.

The prior argument highlighted the negative impact of intervention policy on the United States itself, but this is only part of the argument that should be made. A case must also be made to the morality of United States interventions.

A generally accepted rule of international politics is state sovereignty. While I believe that American democracy should be a blueprint examined by other nations as an example of effective government for the people and by the people, individual countries have their own systems of electing leaders and parties, and this ought to be respected by other nations.

If we, as a nation have an expectation that foreign powers should not intervene in our electoral process, then it is the epitome of hypocrisy to believe that intervention is necessary due to what we consider a flawed election process.

While the current administration has demonstrated a more judicious approach in foreign intervention, the push by some to return to this neo-conservative interventionist policy is a concerning development. We must push for informed decision-making and a restrained approach when considering the use of military force.