History of downtown Pullman

March 2, 2017

Most of us pass through Pullman in four years without the slightest consideration for the history of the place we so frequently call “the promised land.” As proud Cougs, we love our little college town hidden in the hills of the Palouse, that is a given. But to truly love Pullman means to love its unique history and growth, things easily taken for granted and often lost over time.

“The town has been here for around 140 years, so there is a lot of history to it,” University Archivist Mark O’English said. “We tend to think that out in the middle of nowhere nothing happens, but things do happen here.”

When tracing the history of Pullman, the establishment of the town has to be the starting point. Unfortunately, as many origin stories before the detailed recording of historical events, Pullman’s start is mostly hearsay and legend now.

“I don’t think anyone knows [the true origin story] anymore,” O’English said. He has heard three possible stories of the first settlers to establish Pullman in the 1870s.

The town was first named “Three Forks” because it was the location of three merging creeks. Years later, settlers changed the name to Pullman in honor of engineer George Pullman, inventor of the Pullman sleeper car for trains, according to the Pullman Chamber of Commerce website.

Shortly after the establishment of Pullman, two fires virtually destroyed all of downtown, one in 1887 and another in 1890, O’English said.

Yet Pullman recovered, and after Washington became the 42nd state of the U.S. in 1889, the search began for the location of a state college. Conditions for the location of the college included a town with a decently sized local population and satisfactory connections to railway transportation.

A team of three people was sent to evaluate Eastern Washington for ideal locations, and they chose Pullman out of 13 other potential locations within Whitman County, O’English said.

While Pullman did boast a connection to multiple railroad lines, it was mainly the town’s abundance of artesian aquifers that made the construction of a state college possible here.

“This is not really the wettest of places out here in Pullman,” O’English said, “but we had these huge numbers of artesian wells downtown. You could basically just take a drill and have water spurting up.”

There is even a water fountain replica located behind the Neill Public Library with a sign that talks briefly about the wells and their significance to the city’s development, he said.

The public responded positively to the announcement of the construction of the college, then named Washington Agricultural College and School of Science, and there was great celebration throughout Pullman.

“All the big business men in town wanted [the construction of the college] because, you can imagine if a major college is going to come in, teeny tiny Pullman is going to grow dramatically,” O’English said. “They will be able to sell land, they will be able to make a profit.”

O’English, who works in Manuscripts, Archives and Special Collections (MASC) within Holland and Terrell Libraries, has lived in Pullman since 2000. A specialist in WSU history, O’English said Pullman owes a large portion of its growth to the establishment of the college.

Without WSU, he hypothesized Pullman would have probably remained even smaller than Colfax, or equivalent in size to Uniontown. But today, Pullman is the largest city in the county.

“Pullman would have just been 40 or 50 houses that you sail on through trying to get to Colfax or somewhere else,” he said.

In 1892, the college officially opened for its first incoming class of students, and Pullman began to grow drastically to accommodate students and faculty.

Then, in 1910, a severe flood struck downtown, entirely demolishing bridges and several building fronts. This flood might have been the highest the water in Pullman has ever risen, O’English said.

The day after the flood, engineering students from the college constructed a temporary bridge so that people living on one hill could get back across to town proper.

Washington State College (WSU) engineering students help to build a temporary bridge after a flood in Pullman took out the previous bridge in March of 1910.

Following the destruction, there was a big push in the early 1910s to pave the troublesome roads of Pullman, especially in areas of high traffic like downtown, by the train depots and steep hills.

“As you might imagine in a pre-pavement era, horses and carts moving up the hills of Pullman in muddy times was not the best thing,” O’English said.

Several blocks of this more-than-century-old red brick still exist today, although some sections have been asphalted over or lost. Now the bricks even have a state historic dedication.

“[The red brick roads] are pretty gorgeous and not something you see preserved today in too many other places,” he said.

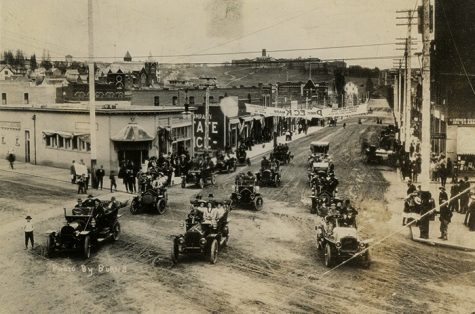

Cars turn off Main Street onto Grand Avenue in 1910. WSU’s clock tower can be seen in the background.

Pullman continued to grow in various, and often dramatic, spurts following wars throughout the 20th century as more and more students began attending college.

“Post-World War II, the town just went crazy because all of the soldiers returned back from the war and so many went to college,” O’English said. “And then we had to grow the college, and grow the housing for them, and more faculty and the housing for them.”

Catastrophe struck again in 1948 with the arrival of another severe flood. After a dike constructed of split-pea-filled sand bags washed out at three in the morning, areas of trailer married-student-housing were flooded in knee-deep water.

O’English shared stories of former military men who formed human chains, all linking arms, so that women and families could walk up and out of the flood zone without falling or getting pushed back by the raging current.

“After the fires and the floods, there are all these stories of the town coming together and finding places to house the students,” he said. “Some of it is just really charming, the small town reaction to something like that happening.”

As you can imagine, traveling to Pullman was often difficult, and both the town and the university relied almost solely on trains before cars replaced railroad transportation in the ‘50s and ‘60s.

However, throughout the 1910s, ‘20s, ‘30s and ‘40s, special student-only trains called “Cougar Specials” were put together at the beginning and end of each school term to transport students back to their hometowns.

“It was kind of like a party bus or like Hogwarts,” O’English said.