WSU researchers find way to use plastic as fuel

Plastics like grocery bags, water bottles, jugs could be used as diesel, jet-grade fuel

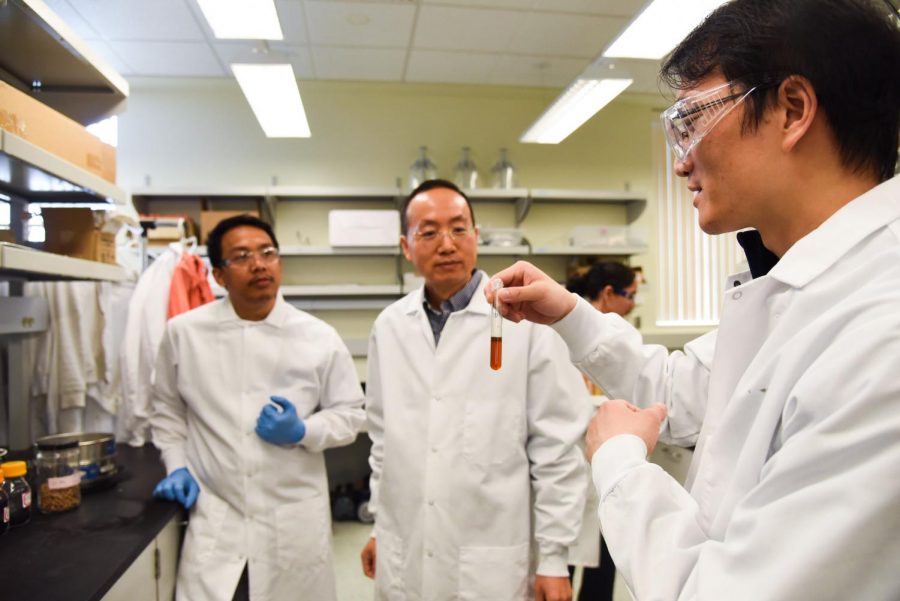

Hanwu Lei and a team of scientists discovered a way to convert carbon molecules in plastic items into fuel.

July 3, 2019

WSU researchers in Tri-Cities have found a way to turn plastic waste into jet fuel. This new process could theoretically use 100 percent of plastic waste material to fuel power jets and semi-trucks.

Plastics like grocery bags, water bottles, milk jugs or other low-density polyethylene materials (LDPE) were exposed to high heat in order to separate chemical bonds, in this case, carbon bonds, within a test tube.

Researches published results of the experiment in the Applied Energy scientific journal, which read that these plastics could all successfully act as jet fuel.

Hanwu Lei, co-author of the article and one of the researchers of the experiment, said in order to extract the desirable carbon bonds within the plastics they had to be exposed to extremely high heat.

During the experiment, LDPE materials were exposed to temperatures from 806-1,060 degrees Fahrenheit. The higher end of that range is as hot as flowing lava.

LDPE plastics were exposed to these various types of temperatures in order to observe their reactions. Some of the LDPE plastics were collected from the office trash can, Lei said.

“If you have [572] degrees for plastic it will just melt it,” Lei said. “Usually you have to be above a certain temperature to decompose the plastic first.”

Once these LDPEs, with the addition of activated carbon, which speeds up chemical reactions and decomposition, were exposed to these temperatures it created a liquid with carbon bonds suitable for jet fuel, Lei said.

“When you add the [carbon activated] catalyst you can break this carbon-carbon bond to convert to smaller molecules so you can have carbon-8, -12 or -16 carbon together,” Lei said. “Jet fuel has a certain range — it has a certain carbon numbers that required so you have to have a chemical match.”

Jet fuel, such as Jet A and Jet A-1, have a carbon number that ranges from 8 through 16, just like the product of this experiment. 85 percent of the plastic fuel, is jet-grade fuel, Lei said, but 15 percent can be diesel-grade fuel.

The diesel-grade fuel, Lei said, can consist of a higher carbon range. These higher carbon bonds are more difficult to break down but are within the range of diesel fuel, he said.

“Sometimes you cannot break down [carbon bonds] like that,” Lei said. “[So] you may have a higher range like a range of carbon-16 to carbon-33, diesel range.”

Lei thinks this method of repurposing and reusing common LDPEs, such as six-pack rings, juice boxes or the plastic bag that seals some cereals, to turn into fuel wouldn’t hurt the environment any more than it has. It would supply the current jet and diesel fuel demand and would be a right step into solving the environment’s climate problem.

“If there are few commercial operations that convert plastic waste into [jet/diesel] fuel and use that — I’m just thinking, this fuel generated by this plastic waste would share the [fuel] market and not increase CO2 emissions,” Lei said. “This would be an intermediate step into solving the plastic problem before we go to all renewable.”