A Wasteful Life: Palouse locals advocate for no-plastic life

College student’s road to zero-waste proves more complicated than initially expected

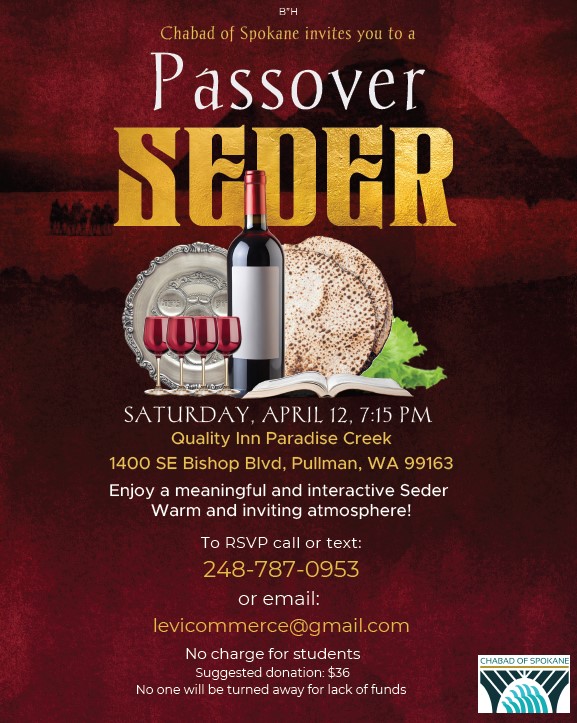

SYDNEY BROWN | DAILY EVERGREEN ILLUSTRATION

“This [climate change] is an emergency, we’re not going to vote-with-our-dollar our way out of this,” Michelle Decourcey, clinical pathologist at WSU’s teaching veterinary hospital, said.

September 9, 2019

Alice Ma has used the same eating utensils since 2011.

The WSU dietitian unsheaths a bamboo fork, a spoon, a pair of chopsticks and a knife from the red-and-white vinyl case. It’s the color of her alma mater, the University of Utah, where she first found her passion for sustainable living and environmental activism.

In front of her sits a collection of items we all use daily, only with an eco-twist. Every day, she carries a reusable water bottle, the bamboo utensils mentioned above, her own Tupperware containers for when she dines out, and a foldable, rectangular plate that she takes to conferences or staff luncheons.

She cleans them, of course, but when you consider the evidence that fast food garbage accounts for 50 percent of litter on city streets, Ma probably saves literal tons of plastic each year.

Three weeks ago, I wrote a column in which I decided to declutter my life and become “zero-waste” with the knowledge that we all produce waste on a constant basis, and sometimes involuntarily.

Michelle Decourcey, a clinical pathologist at WSU’s teaching veterinary hospital, runs a less-waste Instagram account. She was one of the first to point out that my original idea is flawed: no one is zero-waste, but we can all strive to produce less.

Start small, said Dave Sutherland, the board of directors president at the Moscow Food Co-op and a former agronomist for a farmer’s cooperative in Oregon. Make manageable changes first, and get creative.

Get a reusable water bottle. Check. Maybe purchase some produce bags to use instead of plastic wraps found at most grocery stores. Check. Use old totes or buy some at a thrift store to use them at checkout. Check. Maybe go as far as to make your own produce bags, as I did with a tattered, clean cloth jumpsuit that served no other purpose for me. Check. Ask your waiter, politely, for no straw before they leave it on the table. Check.

“I don’t think people expect it [going zero-waste] to be so easy,” Ma said.

WSU registered dietician Alice Ma said she has been using the same set of bamboo silverware for 7 years. “This is just a part of me now,” she said.

Sutherland said reducing one’s waste requires planning, mindfulness and a refusal to buy what you don’t need. This means using the entire chicken when cooking and composting old vegetable scraps. Over time, taking small steps, like politely refusing a straw or recycling belongings in the moving process, will allow one to declutter their life and become less wasteful.

While these steps may seem inconsequential under the grand threat of climate change, Sutherland said the way you spend, or don’t spend, your dollar sends a powerful message.

“When you’re buying something that’s sustainably grown … that matters,” Sutherland said. “That’s casting your vote.”

Because an “eco-friendly” lifestyle seems to be tied in with the health-and-wellness side of Instagram, new eco-tools can easily tempt someone into purchasing a bunch of crap they don’t need, something Decourcey said is the last thing I should do.

As tempting as the idea of cool yarn balls that get rid of the static in your clothes may be, you have to also consider shipping and the waste produced in the process of making these gimmicky gadgets.

Decourcey said that while she loves the sustainable community on social media, she has also seen a number of misleading Instagram posts with the sole purpose of making money, not saving the planet.

“Everything is co-opted by capitalism,” Decourcey said.

The first step, Decourcey said, is to stop making purchases altogether. Since she began her less-waste journey, Decourcey has actually saved money and even paid 16 percent of her student debt.

The idea that I would actually save money blew my mind at first, but it shouldn’t have. The best way to move toward a no-waste life is to avoid plastic. So far, I’ve spent a grand total of $5 on this zero-waste lifestyle, and those dollars were spent on reusable grocery bags.

So what’s the problem with plastic in particular? While materials like glass and aluminum aren’t biodegradable either, both can be reused more often than plastic, Ma said.

Moreover, a study published in the Marine Pollution Bulletin found that 37 percent of plastic produced is single-use. Plastic also accounts for 60 to 80 percent of marine litter.

According to a National Public Radio article, China’s “National Sword” policy passed in 2017 means that the Chinese government stopped accepting most of our recycling. It’s believed that another 111 million metric tons of plastic waste will be displaced because of this law by 2030. For comparison, that equals about 555,000 average-sized blue whales, the largest animals to ever live on Earth.

Maybe this will change the tide — literally — so that plastic itself becomes obsolete. Now that the world’s biggest buyer has shut its metaphorical plastic doors, maybe production will fizzle out, too. This could actually be a good thing, and in my opinion, kudos to China for finally saying “no more.”

Last year, an article in The Daily Evergreen spelled out some of the changes WSU Waste Management made to the recycling system, a harsh reality check for those of us who assume that when we throw our plastic in the recycling bin, we’re doing the planet a favor.

Not necessarily.

Jason Sampson, the assistant director of Environmental Health and Safety, oversees many of the projects WSU Waste Management takes on in order to rectify this recycling crisis. He said laziness from students drives most of the problems they see with recycling.

When one piece of the recycling is “contaminated,” meaning it has food residue or is simply not recyclable, the entire batch is completely useless and goes straight to the landfill, Sampson said.

For Decourcey, who grew up in Portland, composting and recycling from an early age was practically second nature. Then, once China stopped taking most plastics from American centers, Decourcey had an uncomfortable epiphany.

“I went to the recycling center and realized I would have to throw all this plastic out,” she said.

While Decourcey wholeheartedly disagrees with the “a month’s worth of trash in a mason jar” fad, she said making small, easy lifestyle changes can lead to bigger, systemic shifts.

Ultimately, however, we have to hold companies accountable for carbon emissions and wasteful practices.

“This [climate change] is an emergency,” Decourcey said. “We’re not going to vote-with-our-dollar our way out of this.”

Still, there are a lot of ways to feel really guilty about the waste we produce. What about those who wear makeup? Makeup companies produce a disturbing amount of waste, and I’ve purchased products with three cardboard boxes and a pile of plastic just for a 0.8-ounce lipstick. What about if you are craving a burger from a fast-food restaurant, which comes with its own set of waste that’s basically unusable after you’re finished?

To go “zero-waste” means giving up a lot more than I realized, and while I’m willing to make the shift, there’s more to the plastic pollution problem than reusable straws.

Sampson said reducing our plastic intake is great and all, but at the end of the day, we all produce waste just from being alive. Sometimes the technology available doesn’t consider long-term environmental effects and instead tries to fix a problem before we have the ability to do it sustainably. Even more than that, Sampson said water and air quality are currently larger issues that we should be more concerned.

I see what Decourcey means when she says it’s impossible to go zero-waste, and I agree that the best way to combat the death of our planet is to get out and force corporations, the biggest producers of waste and carbon emissions, to change their ways.

But, looking at Alice Ma’s set of reusable tools, it gave me a glimmer of hope that each of us, even in incremental steps, can change our environment.

Part Two is coming soon.

![“This [climate change] is an emergency, we’re not going to vote-with-our-dollar our way out of this,” Michelle Decourcey, clinical pathologist at WSU’s teaching veterinary hospital, said.](https://dailyevergreen.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/web-37-900x600.jpg)