- COVID-19

- Faculty

- Features

- Local

- News

- Pullman Community

- Research

- Research

- TOP FEATURES

- Whitman County

- WSU Pullman campus

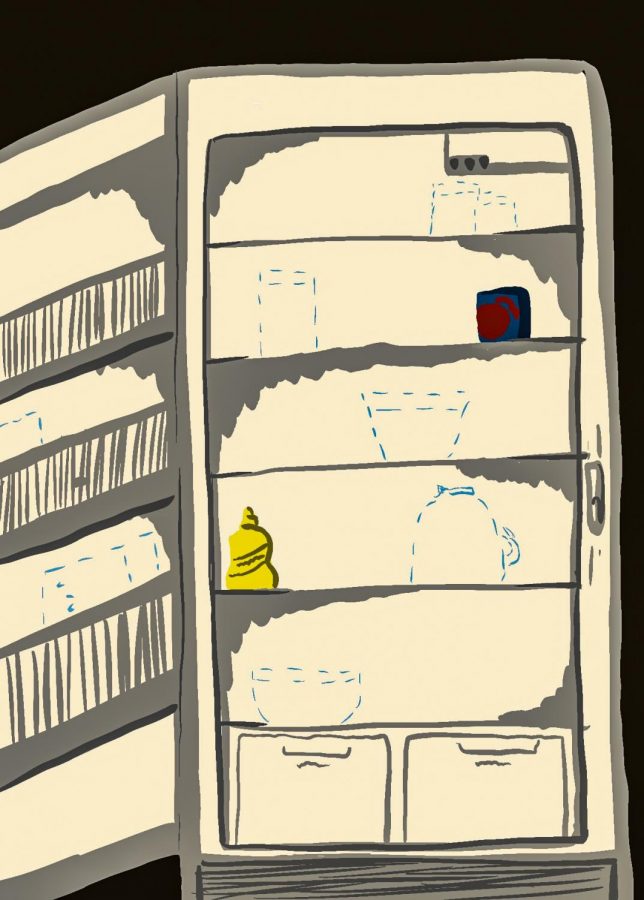

Pandemic leads to increase of food-insecure people in Washington

Over 30 percent of residents say they are food insecure; residents more likely to buy nonperishables, researchers say

A third of survey participants considered themselves food insecure, and a third were also claiming unemployment benefits.

November 30, 2020

A team of researchers found the number of food-insecure people in Washington has doubled from 1.1 million to 2.2 million since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic.

The WAFOOD Survey Team researched food insecurity in the state by collecting data through surveys, said Laura Lewis, WSU director of the Food Systems Program and member of the WAFOOD Survey Team. The team consists of researchers and professors from WSU, University of Washington and Tacoma Community College.

Over 2,200 residents from 38 of the 39 counties in Washington participated in the survey, Lewis said. The survey began in June and ended in late July.

Since the beginning of the pandemic in March, over 30 percent of Washington residents considered themselves food insecure. The team believes between 15-30 percent of residents were food insecure before the start of the pandemic, but they are still trying to establish the baseline for the original percentage, Lewis said.

A third of participants considered themselves food insecure, and a third were claiming unemployment benefits, Lewis said.

Nearly half of the participants felt uncomfortable going into grocery stores because of COVID-19, she said.

Residents have changed their shopping habits, Lewis said. The purchase of perishable foods, like meats and seafood, greatly decreased. The purchase of nonperishable items, like rice and soups, increased.

Twenty-five percent of participants said they were embarrassed to use a food bank or admit they were food insecure, Lewis said.

“I think it’s really important for people to realize that … they may not have thought that they knew someone who was food insecure prior to COVID,” she said. “Chances are, they do now.”

Participants were asked about their education, race, marital status and income. Researchers wanted to know if any of these factors contributed to food insecurity, she said.

Researchers were interested in participants’ ability to obtain food assistance, through using food banks or food distribution centers, Lewis said.

They also wanted to know if participants were using food assistance programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program or the Women, Infants and Children program, she said. People aged 18 years or younger can also access school meal programs.

In Pullman, resources like Office for Access & Opportunity Food Pantry, Community Action Center and Little Free Pantry are available for people to use.

Lewis said she was already collaborating with researchers from University of Washington on projects relating to food systems before the pandemic. University of Washington secured a rapid research response grant to fund a study on food insecurity during the pandemic.

The WAFOOD Survey Team will release another survey regarding the impact of food insecurity on Washington residents during the pandemic.