Teaching global warming helps deniers believe

People who understand greenhouse gas effect believe more strongly in global warming, study finds

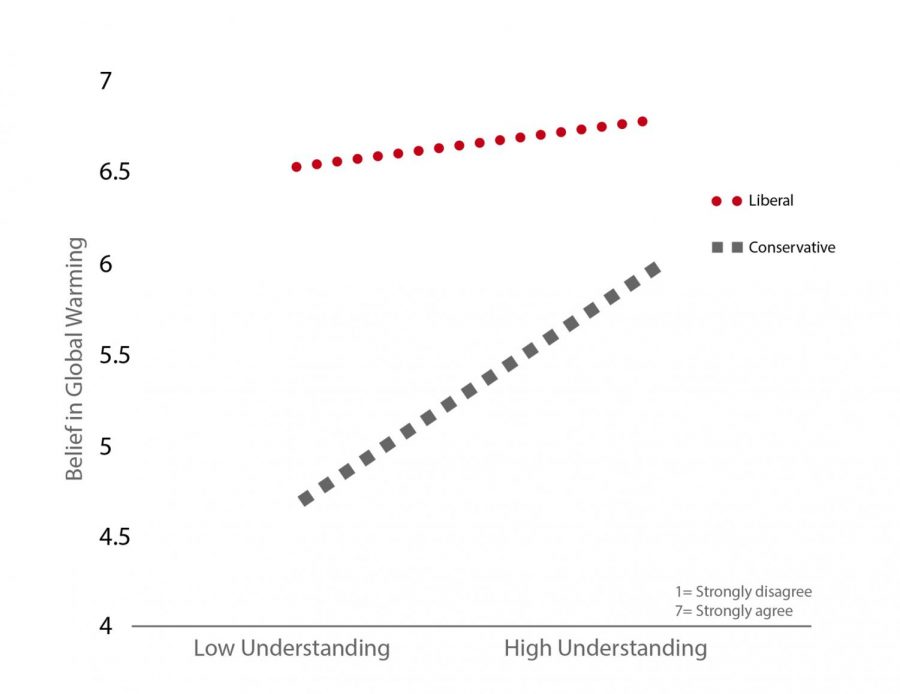

The data shows the average scores for liberal and conservative participants and their understanding of the greenhouse gas effect. When conservatives have a higher understanding of the greenhouse gas effect, they tend to believe in global warming. Liberals tend to believe in global warming more strongly even if they have a low understanding of the greenhouse gas effect.

January 28, 2021

WSU researchers found one of the most effective ways to communicate scientific topics, like the greenhouse gas effect, to those who do not understand is to explain how the process works without condescension.

While researchers found political affiliation had a correlation with individuals’ beliefs in global warming, liberals were more likely to believe in it without knowing the science behind it, said T.J. Weber, former WSU doctoral candidate.

“Conservatives in our sample actually scored better on a scientific literacy scale. That’s partially because fields like engineering, math and STEM fields tend to be a little bit more conservative,” Weber said.

Participants’ basic scientific knowledge was tested in a scientific literacy test, prior to conducting a survey of how much they believed in global warming, he said.

“We wanted to see if people that could explain the [greenhouse gas] effect better had a higher belief in global warming, which is what we found,” Weber said.

Once researchers explained the process, even people who did not originally understand the concept were more likely to believe in the greenhouse gas effect, he said.

Before that test, researchers administered a pre-test that evaluated whether knowledge of the greenhouse gas effect would predict people’s belief in global warming, according to the study.

Participants had to explain how greenhouse gases contribute to global warming in the pre-test, regardless of whether or not they believed in global warming, according to the study.

After the pre-test, researchers taught participants about the greenhouse gas effect. Then three studies were conducted to evaluate the participants’ knowledge, Weber said.

The first study assessed whether learning about the greenhouse gas effect would lead to people believing in global warming more, he said.

The second study measured whether increased belief in global warming would correspond with greater attitudes toward sustainable products and a willingness to invest in them, Weber wrote in an email.

The third study was meant as a follow up a few months after participants learned about the greenhouse gas effect. Researchers found that participants’ increased belief in global warming held over time, Weber said.

“Together, [the studies] represent several related ways of understanding how knowledge of the greenhouse gas effect impacts belief in global warming and related beliefs and attitudes,” he wrote in an email.

Researchers also found that participants who had already believed in global warming prior to learning more about the greenhouse gas effect were mostly liberal, he wrote in an email.

“Liberal participants with the highest scientific literacy had the strongest belief in global warming, though low scientific literacy liberals had greater belief than any version of conservative respondents,” Weber wrote.

Teaching about the greenhouse gas effect had no statistically detectable effect on liberals because researchers cannot increase how much someone believes in global warming when they already fully believe in it, he said.