Water alternatives address aquifer depletion

Conservation efforts decreasing yearly decline; Palouse Basin Aquifer Committee monitoring usage

Cities in the Palouse region — including Pullman, Moscow, Colfax, Albion and Palouse — receive water from two aquifers. The deeper aquifer, the Grande Ronde, is used by all the cities.

April 22, 2021

As the two aquifers beneath Pullman and Moscow continue to be depleted, local conservationists are exploring potential alternative water sources for the region.

“Our water level is declining, and we need to do something about that,” said Robin Nimmer, senior hydrogeologist at Alta Science and Engineering in Moscow, Idaho. “And we are, with the conservation and investigating these alternatives.”

Cities in the Palouse region — including Pullman, Moscow, Colfax, Albion and Palouse — receive water from two aquifers, said Jodi Prout, Palouse Conservation District education and outreach coordinator. The deeper aquifer, the Grande Ronde, is used by all the cities, while the shallower aquifer, the Wanapum, is mainly used by Moscow.

An aquifer is water trapped between layers of sediment, similar to an underground lake, Prout said. In the Palouse region, basalt is the sediment holding the water in place.

The basalt bedrock, or solid rock under loose top layers, makes it hard for surface water to seep back into the aquifers and restore the water levels, Prout said. As a result, the aquifers are losing water faster than it can be replenished.

The Palouse Basin Aquifer Committee monitors water levels in the aquifers. Using a series of monitoring wells around the basin, the committee keeps track of water depth over time, said PBAC chairman Paul Kimmell.

There is no way to tell what volume of water the aquifers contain, so the committee can only monitor the change in depth, Kimmell said.

“The challenge is, ‘How much water is still below us?’” Kimmell said. “Can we be assured that, yeah, we have another 150 years of supply underneath us if we just manage it well? Or do we have 50 years, or do we have 500 years? That is the age-old question for us.”

Researchers at WSU and the University of Idaho are trying to model the rate of recharge in the aquifers. The storage coefficient, or how much water is contained in the aquifers, is unknown, which complicates the problem. Steve Robischon, PBAC technical manager, said researchers are pleased if they can get within one order of magnitude — between ten times and one-tenth — of the true value.

“We will never have enough data to know for sure,” Nimmer said. “That’s why we’re looking into these alternatives now. We’re not waiting until there is a crisis.”

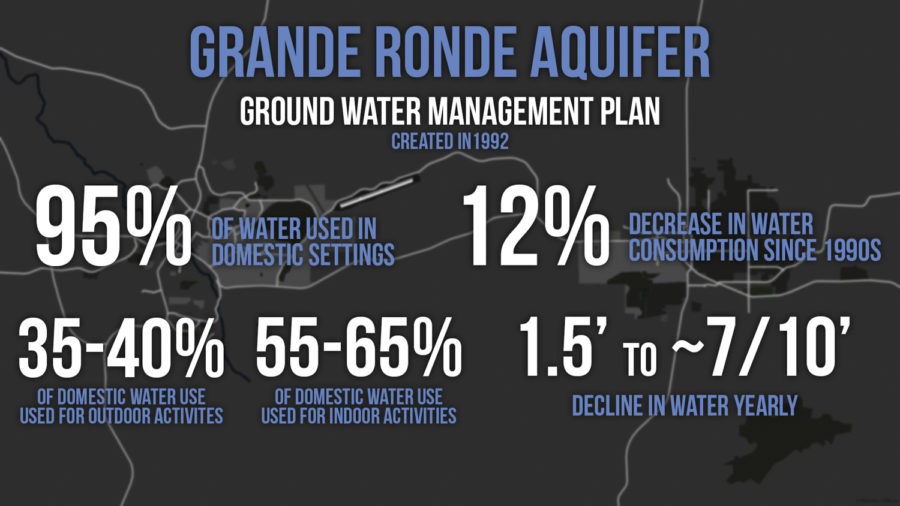

PBAC created a Ground Water Management Plan in 1992 to ensure there is a safe, sustainable yield in the aquifers, Robischon said. PBAC hopes to keep a reasonable balance in the aquifers for future years.

Even with the plan in place, the water level continues to decrease. This means there is an imbalance between water being withdrawn and water replenishing the aquifer, Robischon said.

“You can’t continue to pump when you’re pumping more than is naturally recharged,” he said.

Water use and behavior in the region is improving, especially with increased conservation efforts, Kimmell said. There is about 12 percent less consumption from the aquifers now than in the 1990s.

In previous years, the water level decreased by about a foot and a half each year. More recently, it has decreased by about seven-tenths of a foot each year, Kimmell said.

Only about one percent of the water on earth is available for humans to use, Prout said. The rest is trapped in glaciers or high-salinity seawater.

“This is an issue that’s fundamental to, honestly, us existing on the earth,” she said. “We need to be figuring out ways that we can, hopefully, share and have enough clean water for tomorrow.”

PBAC is exploring four alternatives to using water from the aquifers, Nimmer said.

The first involves pumping water from the Snake River up to a water treatment plant in Pullman or Moscow and distributing it, she said.

The second alternative would be to divert water from the North Fork of the Palouse River and from either Paradise Creek or the South Fork, Nimmer said. Another alternative would also involve two diversions: one from a potential storage reservoir and one from the South Fork of the Palouse River.

The last alternative incorporates several different projects to recharge the aquifers and reuse wastewater, she said.

Kimmell said about 95 percent of the water used in the aquifer basin is used by consumers and businesses.

That water is split between outdoor domestic uses and indoor domestic uses. About 35 to 40 percent of the water is used outdoors for purposes such as watering lawns and gardens, filling swimming pools and washing cars, Robischon said. There are a variety of indoor uses, including washing dishes, showering and flushing toilets.

Farmers use very little of the water from the aquifers because they rely on dryland farming practices. This means they do not use irrigation and instead rely on precipitation to water their crops.

Both Pullman and Moscow have rebate programs to encourage residents to conserve water, Kimmell said. For example, Moscow has a wisescape program, where residents can replace traditional grass lawns with native plants that require less water. Similarly, Pullman provides lawn removal credits for residents who remove water-costly grass lawns.

UI uses treated wastewater to water greenspaces on campus, such as Guy Wicks Field, he said.

Using certain technologies, such as faucet aerators and low-flow toilets and showerheads, can help conservation efforts, Prout said.

People should be mindful of their water usage and opt to use less when possible, she said. This could mean turning off the faucet while brushing teeth or only running laundry once a week on a cold cycle.

Aquifer depletion is an issue that crosses state lines, Kimmell said. The aquifers supply WSU, Pullman and Whitman County on the Washington side of the border and UI, Moscow and Latah County on the Idaho side of the border.

Robischon said students at the two universities seem eager to implement sustainable practices, but they often do not realize they can help conserve water in the aquifers until they have been here for several years.

Prout said part of why WSU was established in Pullman was the abundant source of groundwater. There are artesian wells that supply natural spring water, such as one located at the corner of NE Olsen Street and NE Kamiaken Street, near Neill Public Library.

Water in the aquifers is very high quality, Robischon said. It only needs minimal treatment with chlorine before domestic use.

Treating wastewater and pumping it back into the aquifers could present a potential contamination problem, he said.

“At the end of the day, it’s about our consumers and customers and municipalities,” Kimmell said. “Making sure when they turn the spigot on that there’s water there.”