WSU professor researches more effective ways to recycle

Plastic quality lowers through traditional recycling; $2 million grant will help researchers find new, better method

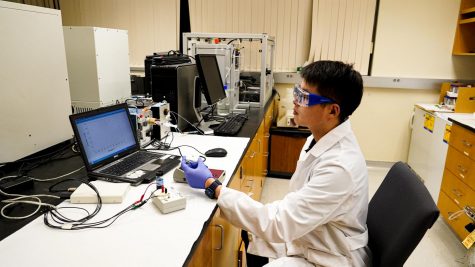

Plastic waste is a problem, so WSU Professor Hongfei Lin is researching how to chemically convert plastic types that are difficult to recycle.

October 14, 2021

Around the world, tons of disposable plastic are thrown away each day, while only about 9 percent of plastic is recycled worldwide.

Plastic materials usually end up in landfills or the ocean. Every year, 8 million tons of plastic will end up in the ocean, said Hongfei Lin, WSU chemical engineering and bioengineering associate professor.

It takes thousands of years for plastics to decompose, Lin said. When plastic breaks down, it turns into microplastics that can be ingested by humans and animals. Every year, around 300 million tons of plastic waste is produced.

“Those are the plastics that we only use for one time,” Lin said. “And then we throw them away. And that’s a big waste.”

Because of this huge plastic waste problem, Lin and his fellow researchers have received a four-year $2 million grant from the National Science Foundation Emerging Frontiers in Research and Innovation program to research a better way to cost-effectively recycle plastic.

The conventional method of recycling plastic is not the best solution, he said. When plastic is recycled, its quality downgrades and has to be mechanically sorted. Not all plastic can be recycled using traditional methods.

There are thousands of different types of plastics like polyethylene, polypropylene, polyvinyl chloride and polystyrene, which have fibers that are incompatible with traditional recycling methods, he said.

During recycling, different types of plastics are mixed together, melted at high temperatures and remolded. A different and possibly better way of recycling would be to chemically convert plastics to monomers using catalytic processes, Lin said.

“So we are going to design a very selective catalyst to deconstruct those chemical bonds,” he said. “With those smaller molecules, if we have a good [selection], it’s possible that we can convert them to usable products.”

The chemical bonds in the plastics will be broken into smaller and smaller molecules by the chemical recycling process. Monomers are the building blocks for plastics and valuable chemicals, he said.

About 80 percent of all plastics could be recycled using the catalytic chemical recycling process, he said. The plastics could be converted to useful products like hydrocarbon fuels. This creates a closed-loop recycling system that could help create a more sustainable future.

Making the new technology cost effective will be a challenge, Lin said. By using predictive computational methods, researchers will be able to find highly efficient catalysts for chemical recycling.

Once the chemical recycling method is more cost-effective, it is more likely to be widely adopted by recycling companies, he said.

“Our group will carry out these projects to contribute to achieving the goal of making our society and environment more sustainable,” he said. “That is why my group is called ‘Catalysis for Sustainability.’”