WSU has begun researching skin regeneration

WSU has begun research to revitalize older skin

July 8, 2022

Researchers are examining how to regenerate skin without scarring by reactivating Lef1 expression in adult fibroblasts to reprogram the skin.

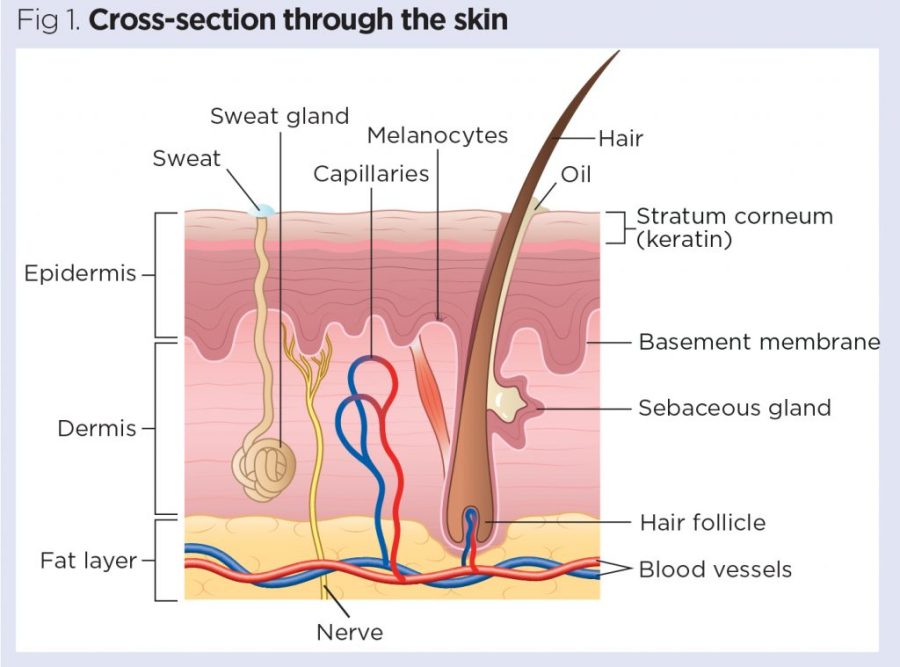

Fibroblasts are cell types dominant in the dermis, the thick middle layer of skin. They are classified into subtypes, with each having a specific function and the potential to aid in healing wounds, said Sean Thompson, graduate student in the School of Molecular Biosciences for the College of Veterinary Medicine.

One subtype is the palitary fibroblast (PFs), a broad subtype of firbroblasts. Fs turn into dermal papillae, a cell type that sits at the base of the hair and signals hair growth. PFs are present in embryonic or young skin and degrade over time. They are absent in older skin, which prevents the regeneration of hair follicles and skin, along with scarring, Thompson said.

Young skin is able to fully regenerate without scarring due to PFs and the LEF1 transcription factor, a protein in young skin that can activate or deactivate genes in the DNA. Reactivation of LEF1 expression in adult fibroblasts could support regenerative outcomes, or “anti-aging,” he said.

A research team led by Ryan Driskell, assistant professor at the School of Molecular Biosciences, is researching how to reactivate the young gene and the Lef1 transcription factor in adult skin. The goal of the project is to reprogram adult skin to have younger properties and allow it to regenerate to its original state.

“Once a scar heals, it is fully done [but] never as good as the original tissue,” Driskell said. “If you continuously get wounded there, eventually your skin may not exist in that spot. “[We] want to understand how to regenerate skin because [the] skin is an important part of our life.”

In Aim 1, researchers tested Driskell’s hypothesis of whether it is possible to reprogram adult skin to gain the properties of young skin, Driskell said.

“The basic principles of skin formation, development and the ability to even regenerate those basic principles can also be used for other tissues because other tissues use the same principles to reform themselves during injury,” Driskell said.

“The aim was to test whether it is possible to turn on an embryonic gene as distinct cell types to reprogram adult skin to have kind of like young skin properties,” Driskell said. “[Essentially], can we reverse aging without causing harm?”

He said his hypothesis was correct, as the reprogramming did not harm the skin. The action also gave the skin beneficial properties, such as healing.

In Aim 2, researchers will use next-generation sequencing to examine skin regeneration. They will also investigate the function of LEF1 on a DNA level. LEF1 is a transcription factor or a protein present in embryonic skin. A transcription factor can turn on and off genes in nearby DNA, Driskell said.

“If you understand the network, how to control the blueprint of DNA properly and each of the different cell types, then you could recreate your skin as you did during embryogenesis,” Driskell said. “That way we can regenerate [skin] as you did when you were an embryo.”

Researchers will use a transgenic model or a mechanism where researchers can manipulate DNA that will help with the research process, he said.

“Transgenic model systems are the mechanism for us to test the hypothesis of whether genes can be turned on and off in a system,” Driskell said. “[We will] see whether it is harmful or beneficial, and in this case, it was beneficial.”

In Aim 3, researchers will examine how young skin heals in comparison to aged skin. They will age the model systems to test their hypothesis, he said.

“The idea is by turning on these genes, does that make our model systems age as much [and] have healthier properties,” Driskell said. “That takes a long time because you must age the models. Otherwise, you are not proving anything.”

The five-year project is in the beginning stage and is expected to end in 2025 or 2026. Researchers will then examine how to utilize drugs to turn on the genes, he said.