A chapter of the Association of Native American Medical Students was officially established at WSU Spokane last November.

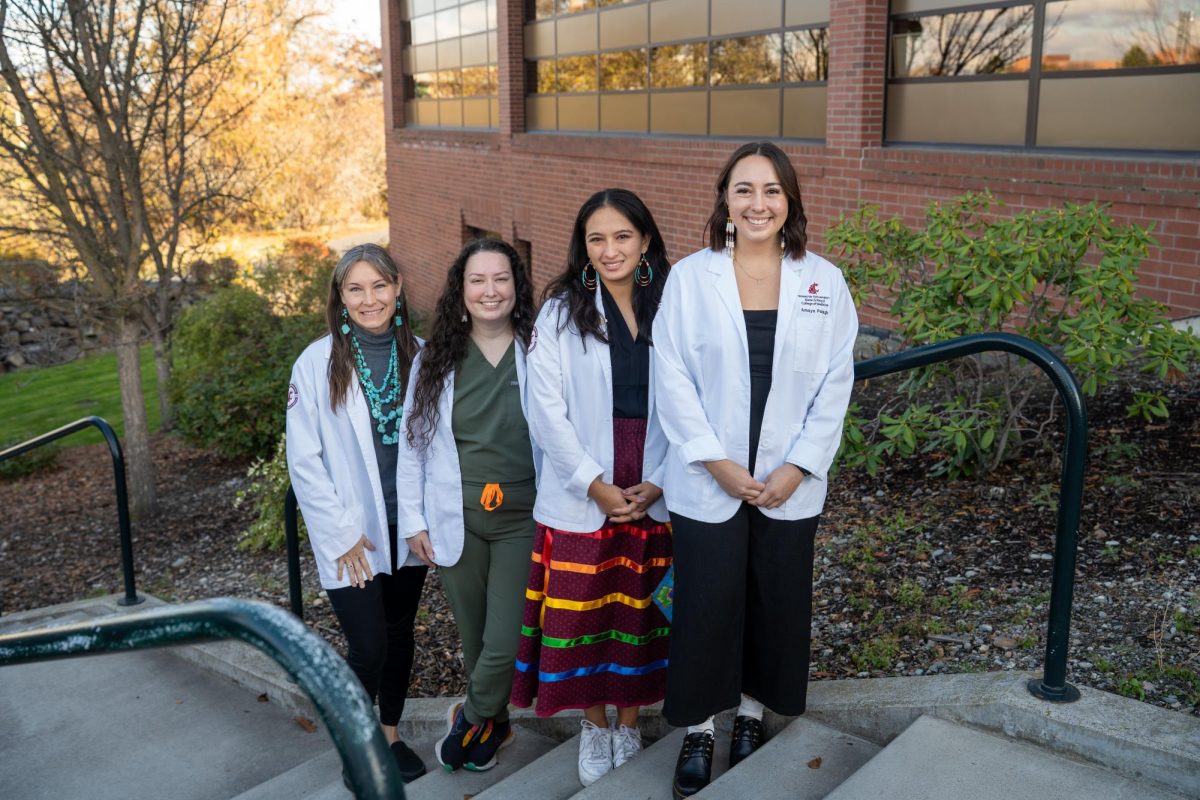

Efforts to establish the ANAMS WSU chapter began in 2021 with Dr. Naomi Bender, Native American Health Sciences director, and medical students Lexie Packham and Calysta Bauer. Packham, Standing Rock Sioux tribal member and second-year medical student, serves as chapter President while Bauer, Navajo Nation Todích’íí’nii clan member and second-year medical student, serves as chapter Vice President.

They were then joined by Chantelle Roberts, Chickasaw tribal member and second-year medical student, and Amaya Pelagio, Inupiaq tribal member and first-year medical student. Roberts and Pelagio serve as Secretary and Treasurer of the chapter. The four are currently the only members of the chapter.

The chapter has received funds from WSU’s Native American Health Center as well as Registered Student Organization funding from the Elson S. Floyd College of Medicine, Bauer said. They are also applying for grants such as the Empire Health grant.

The chapter intends to use current and future funding for goals such as attending culture awareness conferences, an Association of American Indian Physicians conference and various workshops, she said. Establishing a strong sense of community and creating an environment that promotes education is one of the core goals of the chapter.

“Our short-term goals [are] really based around helping us as health professionals develop a community, as well as put us in spaces where we can educate and familiarize ourselves with tribal healthcare systems and individuals and [connect] that work with tribes in the area,” she said.

The chapter also aims to strengthen relationships with local tribes providing funds for Native American students to conduct away rotations on reservations, Bauer said. They also aim to work more closely with Native American youth.

“Long-term, I would say we’re pursuing a lot of involvement with the reservations in the Spokane area,” she said. “Bringing them on to campus, giving them an idea of what we as medical students do on a day to day [basis], all the way up to potentially exposing them to what our lab looks like. As well as talk about career opportunities and even go to the school and do little workshops.”

Seeing WSU’s medical curriculum be more accepting of indigenous health practices is another one of the chapter’s hopes, Roberts said. They hope to do this by creating the possibility for a parallel education through a journal club aimed at colleagues, faculty, staff and others in the medical field.

“[We can help them] understand incorporating traditional medicine or just being able to approach the indigenous patient and understand their [socioeconomic] status and their culture and how it’s all very different,” she said. “[We want to introduce] more cultural humility specific to indigenous health.”

Attempts to integrate Native American traditional medicine with Western medicine present many challenges as it is difficult to narrow down what Native American medicine looks like due to the multifaceted health practices of every tribe, Roberts said. While food is a common denominator in most aspects of indigenous health, every tribe or clan member will have a different idea of how medicine should be practiced.

“I served at Indian Health Services for about five years in family medicine, serving primarily with the Yakima tribe, and even with my upbringing and understanding it was difficult for me to try and integrate those two things,” she said. “However, I think there’s a way to do it. That’s part of our goal here, to say that you don’t have to have the answer.”

Other difficulties in integrating the two worlds of medicine stem from differences in how they are legitimized, Packham said.

“Our medical school’s curriculum is very similar to all medical school curriculums in that it’s evidence-based and has all the studies to back it up, and our traditional ways of healing aren’t necessarily codified that way,” she said. “When I started medical school, [I felt like I had] to put aside a lot of [my] cultural practices in order to be a good doctor. Not to say that we would necessarily use cultural practices on our patients but for ourselves.”

The pressures of medical school also make conversations on the possible introduction of Native American ideas to Western medicine difficult and the possibility for rejection make these conversations difficult, Bauer said.

“The way I personally think and approach patients is different than how a lot of my peers, who are non-native, do. Trying to fit myself into a space where I can bring both my own ways of processing, thinking, and acting with the ways that I should be as a doctor [is] something I’m still going through,” she said. “Hopefully, with this group, [we can] start integrating some education into ESCOM that will be easier for people.”

The chapter not only seeks to make these kinds of conversations easier for themselves and fellow Native American medical students and professionals but for patients as well, Roberts said. They aim to reduce the stigmas surrounding traditional medicine and make conversations between clinicians and their indigenous patients easier and more open.

This allows doctors and other medical professionals to work with patients who may want to incorporate their traditional health practices, Bauer said. These conversations show patients that they are supported by their doctors.

Support and trust from doctors are vital to Native American patients as Western doctors have historically inflicted pain and trauma on their indigenous patients, making it difficult to establish trust even today, Packham said. This increases the importance of having more Native American doctors and health practitioners.

“I certainly celebrate every Native person who wants to become a doctor and serve their communities but also serve non-native communities,” she said. “I think we’re just as effective doctors wherever we’re serving.”

The chapter also seeks to secure the future of Native American youth and those living on reservations by mentoring them and exposing them to the possibilities of a medical career while maintaining the possibility of returning to the reservation, Bauer said. This is due to the tendency for those who leave the reservation for a healthcare career tend to not want to return.

“I am definitely going back…and I want to be able to show people that we as Native physicians aren’t just leaving because we think we’re better or because we want to go somewhere else or because we don’t see a future for those home communities,” she said. “You can go take from education all the things that you need [and] come back so that you can work with the community to elevate [and] help that self-determination.”

Those who are unfamiliar with the vastness of Native American culture and their health practices are encouraged to simply ask, Bauer said.

“This is one of those topics that people respect but they’re too scared to ask questions. I would rather have someone ask questions, and it’s not a big deal because they’re interested in getting to know more about the topic,” she said.

WSU’s chapter of ANAMS differs from its fellow chapters as it includes Native American health professionals and not just medical students, Packham said. This means that the chapter extends its membership to those who study or work in dental, pharmacy, or nursing.

While membership primarily applies to graduate students, undergraduate students across the WSU system are encouraged to volunteer with the chapter, Packham said. Those who are interested may reach out to chapter officers through their emails: alexandra.r.jones@wsu.edu, calysta.bauer@wsu.edu, chantelle.roberts@wsu.edu and amaya.pelagio@wsu.edu. Those interested in updates from the chapter and its events can check the WSU Native Center Facebook page.