Mexican professor speaks about immigration

Immigrants are losing their cultural heritage after coming to the US

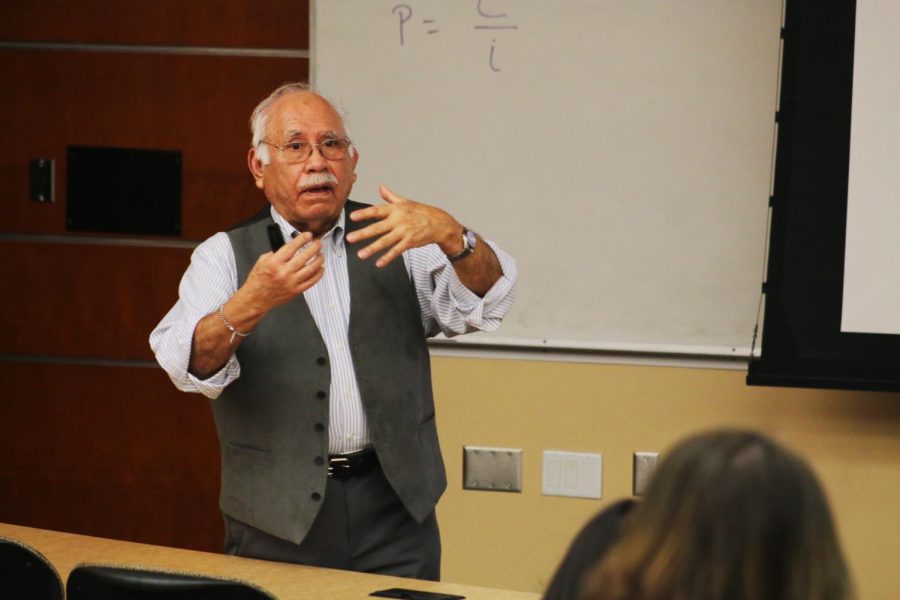

Emeritus professor at the University of Washington Carlos Gill explains the importance that recording and documenting his family had to him, Thursday evening in the CUE building.

A former professor from the University of Washington visited WSU to speak about immigrant families’ experience of losing their cultural heritage from American assimilation.

Carlos Gil traced his family’s immigration experience in a presentation called “From Mexican to Mexican American: A Family Immigration Story.”

Students scattered the auditorium of room 202 in the Samuel H. Smith Center for Undergraduate Education, sitting attentively and taking notes while listening to Gil. The presentation was hosted by WSU’s Common Reading Program and Humanities Washington.

Gil said many reasons people have immigrated to the U.S. is to seek economic opportunities and escape political persecution, like his family did during the Mexican Revolution.

“When people migrate, they migrate for certain reasons,” he said. “People don’t migrate willy-nilly. Many Americans have no concept of these factors that motivate people to leave their homes and go someplace else.”

He said during the ‘20s, ‘30s and ‘40s, U.S. job agents representing companies and the government set up booths close to the Mexican border to offer jobs to immigrants.

“My family in many ways exemplifies these ideas here,” he said. “My uncle Pascual, as he crossed the border within two blocks, he was stopped by a guy who said ‘Do you want a job? Give me your name, I’ll meet you at the hotel. We’ll put you on a train and take you to your job.’”

This was the start of Mexican and U.S. governments coming together to create a unique economic relationship which is not found anywhere else, he said.

During World War II, the U.S. set up the Bracero Program to guarantee decent living conditions and protection from military enlistment to working Mexican immigrants.

Gil said this was done to sustain the number of agricultural workers in the country due to so many workers getting new jobs to help the war effort.

The 1992 North American Free Trade Agreement was an agreement between Mexico, Canada and the U.S. to trade and sell goods with one another without tariffs. Gil said this was another example of bolstering Mexico’s relationship with the U.S.

On Jan. 29, President Donald Trump signed the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement to replace NAFTA. According to the Office of the United States Trade Representative, the new agreement is rebalanced to support a 21st century economy that better benefits American workers and agriculture.

“The American economy acts like a giant magnet that brings in the workers that are surplus in Mexico,” Gil said. “If you look at the way we’re treating Mexican immigrants today, you’d think that this had never happened. All of this is swept aside.”

Gil said the process of becoming American for immigrant families is a challenge because their cultural values and background clashes with American culture.

“Mainstream Americans have no idea of these conflicts and adjustments that have to be done culturally within the privacy of a family,” he said. “The idea of staying home overnight with somebody; remote, just a totally remote idea that just didn’t happen. It produces conflict.”

This creates internal trauma in many immigrant families including his own, Gil said.

Gil’s last topic was about immigrant families losing their cultural heritage throughout generations of clashing conflicts between American and Mexican cultures.

He said his grandkids now only have half a bag of “cultural baggage” compared to five bag when his uncle first immigrated to the U.S.

“Assimilation is not an easy thing,” he said. “It is very hard to control or reduce it no matter what you do.”

Whether that is a bad or good thing depends on the person, he said.

Larry Fox, a former WSU professor, said he has lost much of his German heritage because his grandmother wanted to integrate into American culture.

“By the time my father was born, German was never spoken and I don’t have a clue,” Fox said.

Fox questioned where the balance was with assimilation into a new culture for immigrant families.

“It depends on where you want to go and what you want to become,” Gil said. “If you’re a mathematician, the cultural elements may not be that important and you’ll be as happy as can be.”

For others like himself who had to work with culture, music and history, it may be much more important to avoid being rolled over by assimilation, he said.

Karen Weathermon, director of WSU First-Year Programs, said Gil authored an essay about Washington’s Hispanic communities which was published by WSU and put into the state’s centennial.

Gil’s background matched one of topics the Common Reading program wanted to cover this year, which was immigration, Weatherman said.

Jakob Thorington is a spring 2020 graduate who majored in journalism and media production at WSU. Thorington loves sports, film and video games.

Charles Guptill • Jan 31, 2020 at 7:16 pm

“If you look at the way we’re treating Mexican immigrants today, you’d think that this had never happened. All of this is swept aside.”

This quotation infers that Americans don’t like Mexican immigrants. You assume that we would not accept immigration as occurred in the early to mid 20th Century. Go back to that model of inviting immigrants in and stop encouraging those people to sneak across the border, breaking our laws and bringing in a criminal element. The responsibility for the current paradigm rests with those leaders and employers who sought out laborers they didn’t want to pay a full wage, wanted to put them in jobs that no one else would do and not provide the labor protections afforded other workers or was looking for a way to bring in volumes of individuals above what an orderly system could handle, with the plan to provide welfare and establish them as voters for their party. These are not the only reasons behind a system which flaunts the laws of our nation. Any animosity towards this classification of individuals can be said to result from the idea that “no one should be above the law” it only encourages others including current citizens to believe they don’t have to follow laws either.

Keeping the cultural diversity will always be difficult outside the family circle. We have always been considered a melting pot. As generations of people who are diverse from the mainstream of America enter our society the need to fit in will always draw them away from their roots.