WSU researchers test environmental samples for coronavirus genetic material

Samples of soil, wastewater, stormwater will be collected; infected humans shed viral particles into the environment

Humans and other animals shed coronavirus particles when they are infected. These particles are spread throughout the shedder’s environment.

June 21, 2020

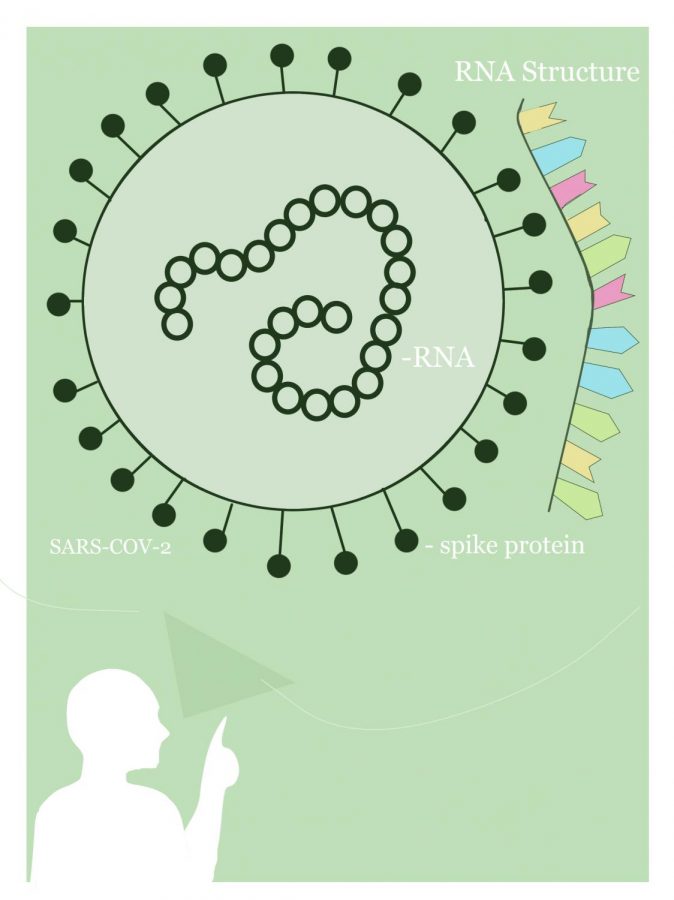

Testing environmental samples for pieces of RNA, the single-stranded genetic material of coronaviruses, may help WSU researchers determine how long the virus can persist outside a host.

Researchers will collect samples of wastewater, soil and stormwater from both urban and rural areas in Washington and Idaho, said Courtney Gardner, assistant professor in WSU’s Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

They will compare these post-pandemic samples to ones collected before the start of the pandemic, Gardner said. This will help researchers determine how persistent the virus is in the environment, and if it could spread in the environment across different areas.

Gardner said humans and other animals shed coronavirus particles when they are infected, which means they release particles of the virus into the air and environment.

“That [shedding] process extends to human waste,” Gardner said. “Wastewater can be a pretty good indicator of the amount of coronavirus circling in a population.”

In an urban area, the amount of coronavirus particles in wastewater begins to increase about seven days before positive cases increase, she said.

“That seven-day period … could give us an indication of how bad the problem is if we’re seeing a rebound in coronavirus cases,” Gardner said. “It could also give public health officials a little extra time to start putting some countermeasures into place.”

Gardner said the environmental testing they plan to do in Pullman and Moscow will help them gain a better understanding of that predictive window, which is likely different in rural areas.

Tyler Patrick, master’s student in environmental engineering, said researchers will use different testing kits for each type of environmental sample. For each test, they will separate the genetic material from the soil or water and run a polymerase chain reaction test.

PCR involves taking short sequences of genetic information, called primers, and mixing them with the sample RNA, Patrick said. If the primers bind to the RNA, many copies of the sequence will be made. The presence of those copies confirms that a sample contains coronavirus genetic material.

Gardner said her work builds on research done in and outside of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which sequenced the genome of coronavirus. Other researchers also published primer sequences, which are what allow WSU researchers to identify coronavirus RNA.

Researchers working with the samples in the lab wear protective gloves, goggles and lab coats, Gardner said. The first step in processing a sample is to extract the nucleic acid from the protein coat, which makes the virus less harmful to humans.