Removal of Brucellosis protein combats bacterial infection

Consumption of unpasteurized dairy products causes bacterial infection

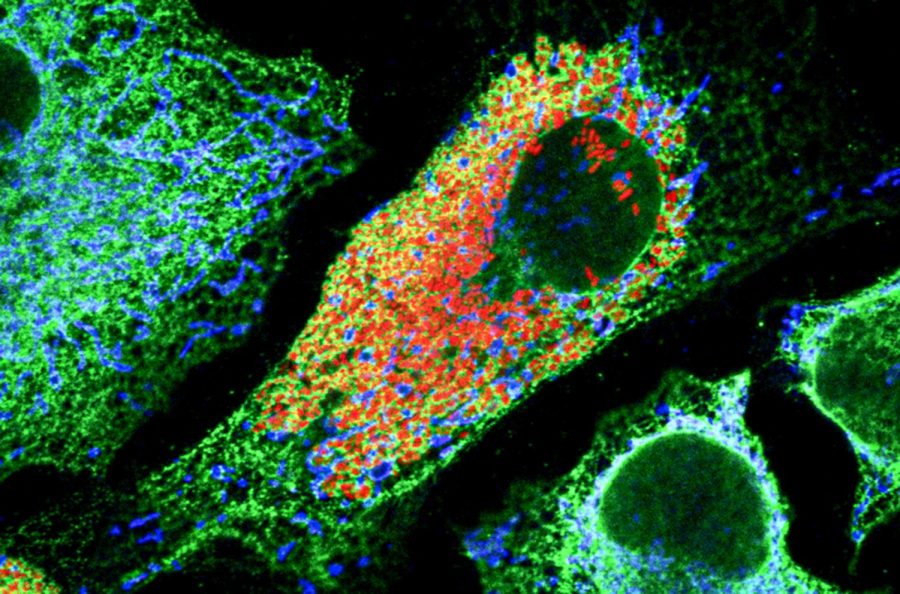

A human cell infected with Brucella abortus bacteria (red) that multiply within their intracellular niche (green).

December 2, 2021

WSU researchers discovered that the removal of a protein could help combat an infectious disease called Brucellosis.

Brucellosis is a livestock disease that can be transmitted to humans through contact or consumption of unpasteurized dairy products. It can cause animals to have miscarriages but is not deadly to humans — however, it can become a chronic disease in humans, said Jean Celli, professor in the College of Veterinary Medicine.

Once transmitted to humans, it causes flu-like symptoms. In severe cases, it can cause arthritis, heart inflammation or neurobrucellosis, which affects the brain, Celli said.

Antibiotics are effective in treating the disease during the initial phase, he said. Once it reaches the chronic stage, it is much more difficult to fully recover.

“The mortality rate is very low, but it can make you miserable,” he said “It is really hard to get rid of all the bacteria and there can be relapse of the disease.”

Brucellosis is similar to Lyme disease. It is difficult to treat and has recurrent symptoms, Celli said. But it is less prevalent and has been eradicated in livestock in the U.S for decades, with the exception of some areas, like with wild boar in the South East and elk and bison in the Yellowstone Greater Area.

WSU researchers have found a way to remove a certain protein in Brucella to combat the disease, said Elizabeth Borghesan, fourth-year graduate student studying immunology and infectious diseases.

Borghesan said she started working with the protein in August 2021, after picking up the research from a previous graduate student. The researchers recently published a study on their progress so far.

Celli said he has been researching the bacterium for 20 years. He has studied how certain kinds of bacteria can invade human cells, proliferate inside and cause infectious diseases. He discovered the Brucella protein in 2012 and has since looked at its function, but did not identify its role until roughly two years ago.

A human’s immune system has specific cells, called macrophages, that can detect foreign particles like bacteria, then capture and destroy them, Celli said. But Brucella is capable of avoiding being killed once it has been captured.

Brucella injects effector proteins — proteins that manipulate the host cell response — into the macrophage. Each protein has a specific function and target to change the function of the cell and help the bacterium, he said. The bacterium then takes over the cell.

Once it survives, Brucella creates an intracellular niche where it can proliferate and then exit to enter other cells, Celli said.

WSU researchers are studying what a specific effector protein does to the cell by removing it, he said.

“Initially we saw that when we removed the protein from Brucella, the bacterium was not able to replicate quite as efficiently,” Borghesan said. “We knew that BspF, the protein, is involved in maintaining or promoting replication of the bacteria.”

The first step of the research was to determine what the protein did to the replication process. If it can replicate, then it is able to survive, she said. The team began to look at specific proteins the host cell has and how the BspF protein interacts with them to understand how it interferes with the pathway.

The consequences of the protein are known, but it will be important to figure out how the protein is working to prevent alterations from occurring, Celli said.

“When we figure out the function of one of these proteins, this doesn’t mean that we found the magical silver bullet against the disease because it only has a small contribution to the whole process,” he said.

The team also found that the protein targets a specific pathway in the host cell and rearranges the response to Brucella to the bacterium’s benefit, so it can replicate and thrive, Borghesan said.

This rearrangement could help Brucella acquire nutrients for it to grow and multiply. The pathway the protein targets helps bring nutrients from the outside of the cell to the inside, she said.

The goal is to eventually pinpoint which cellular pathways need to be targeted to prevent bacteria from replicating, without affecting human cells, Celli said.

Long term, it will be important to understand the function of all of the proteins to determine how many need to be targeted to prevent the replication of Brucella, he said.

For many decades, bacterial infections have been controlled with antibiotics. But bacteria have since developed resistance, so there is an urgent need for more approaches, he said.

“There’s this new school of thought that if you target the host instead of targeting the bacterium, and you target a function that is essential for the bacterium to do its intracellular cycle,” Celli said. “You can potentially prevent a bacterium from replicating without having this problem of the bacteria generating resistance.”

This is because the bacterium is no longer targeted, he said. The cell is incapable of supporting the bacteria, which is called host targeted therapies.

Host targeted therapies have not been tested on individuals affected by Brucellosis; it is still in the testing phase with other diseases, he said.

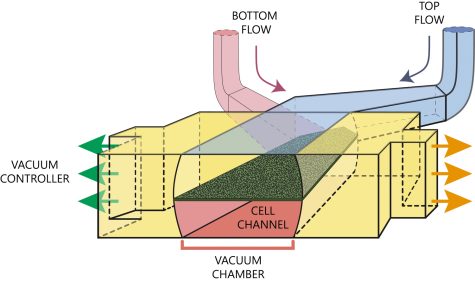

There is no work done in the lab with animals that are natural hosts because it is difficult to work under biocontainment with large animals. Cellular models grown in culture are primarily used, Celli said.

The team is using Brucella abortus, which is the species that predominantly infects cows, to do the research, Borghesan said.

He said it is difficult for the team to get their research funded because Brucellosis has not been considered an important human disease for a long time, Celli said.

“We care about diseases that have worldwide importance, and that’s actually kind of a changing mindset,” he said. “It is important to think broader than just your own country when you think about global diseases.”

Brucellosis has been eradicated from livestock in the U.S, but it is still a global issue that needs attention. Millions of people worldwide are chronically infected with Brucella, he said.

“There is a stage where developed countries have a moral duty to do something about it,” Celli said.