The science of shimmer: iridescence in bird feathers

Bird feathers owe their brilliant hues to pigments, specialized structures

‘Most feathers owe their tones to pigments: organic compounds scattered through the feather. Melanin, the pigment responsible for black, brown and tan hues, is produced by birds and resides in feather structures called melanosomes, according to Audubon.’

January 27, 2022

A glint catches your eye. The fiery metallic shine belongs to a Calliope hummingbird, who hovers curiously in front of you. Then in a shimmering blur, it is gone, leaving your eyes ablaze with nearly unbelievable colors.

Many bird species are dazzlingly bright, especially compared to most other animals. Their feathers are truly works of art. How do they do it?

The incredible colors of hummingbirds and some other birds are the product of evolution. Birds have perfected the science of color. All feathers are built out of keratin, the same substance in human fingernails and hair.

Most feathers owe their tones to pigments: organic compounds scattered through the feather. Melanin — the pigment responsible for black, brown and tan hues — is produced by birds, and resides in feather structures called melanosomes, according to Audubon.

Melanin is also a prominent pigment in human skin and hair. Yellow and red hues, like those seen in flamingoes and goldfinches, are the work of carotenoids. Birds absorb carotenoids from their food.

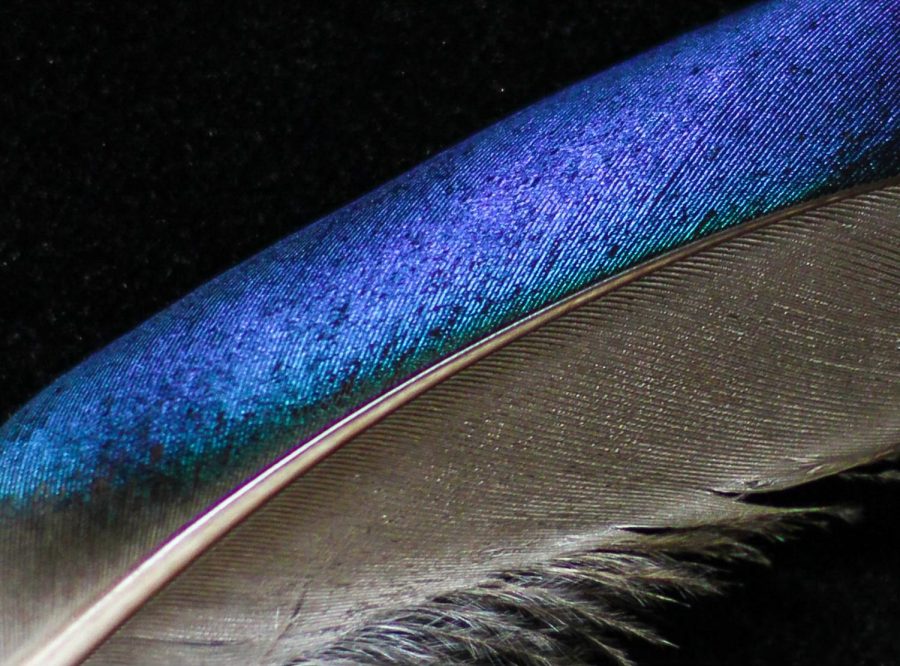

The creation of iridescence, however, depends on another strategy. Instead of simply filling the feather with pigment, iridescent feathers have specialized microscopic structures that reflect light in a more impressive manner. The secret lies in stacking layers of melanosomes and interspersing tiny air pockets, according to Audubon. Essentially, the feather acts as a prism.

“The amazing thing about iridescence is that it’s totally structural, like an oil slick; from some perspectives, the feathers are black, and from others, they are, well, iridescent,” said Daniela Monk, WSU professor of ornithology.

The air pockets scatter light while the melanin absorbs certain wavelengths, reflecting a select range of them. This produces a single, vivid color, like the blue of a Steller’s jay. Because these structures do not rely on pigment, they appear brown if viewed from the underside. Their reflective properties only work in one direction.

Hummingbird feathers produce a rainbow of hues. Their melanosomes are pancake-shaped; instead of consistent air pockets, hummingbird feathers have scattered ones, according to Audubon.

These filter light into a variety of different wavelengths, depending on the angle from which they are viewed. This is why the color of a hummingbird’s gorget, or throat feathers, shifts and morphs as it zooms past.

Why have birds evolved such colorful feathers?

“The purpose of iridescence is for display purposes, attracting the attention of the opposite sex, or for species recognition,” Monk said.

Research offers many explanations, but the most accepted theory is to attract mates; brighter colors indicate better health. However, these colors come with costs. Along with making a bird hot to potential mates, shimmering feathers heat up faster. Spanish researchers found iridescent feathers can be up to 5-degrees Celsius hotter than surrounding pigmented feathers.

Researchers at Akron University in Ohio discovered iridescent feathers shed water less efficiently. Iridescent feathers also make it undoubtedly harder to hide from predators. Since iridescent feathers pose challenges to a bird, those that shimmer the brightest prove their fitness to potential mates.

Peacocks, magpies and hummingbirds are all prime examples. Feather structures found on fossils provide evidence that certain species of dinosaurs — including Archaeopteryx, Microraptor and the recently discovered Caihong juji — grew flashy iridescent feathers to attract mates, according to National Geographic and the National Science Foundation.

Iridescent plumage may also be a form of communication. Since the color of the plumage varies depending on how it is angled to the viewer, perhaps the hovering and twisting of hummingbirds are sending a message to their fellow fliers.

Rufous hummingbirds are notoriously territorial. Their iridescent plumage could be an important part of communicating with rivals.

Like many bird species, hummingbirds are tetrachromatic. Instead of having three types of cones in their retina, they have a fourth that allows them to see ultraviolet light: a section of the spectrum invisible to humans.

Iridescent feathers reflect UV light particularly well, providing support for both the communication and mate attraction theories, according to research from Cornell University.

Now that you know the science behind shimmer, take a second glance at the next bird you see. Many birds on campus, including starlings, crows and magpies, put on stunning displays of iridescence.