Researchers aim to improve soil health, crop quality with biosolid testing

Researchers will test biosolid effects against that of synthetic fertilizers, unfertilized treatments

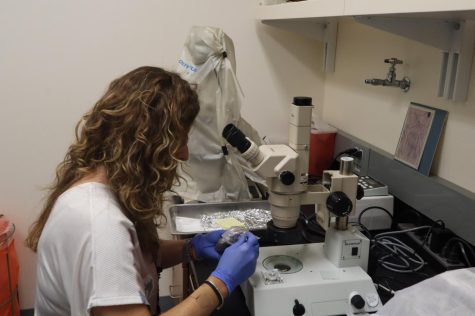

Doctorate student Madeline Desjardins takes deep soil cores to quantify soil carbon in a long-term biosolids experiment in Douglas County, Wash.

June 23, 2022

WSU researchers are examining the effects of biosolid application on soil health and crop productivity to help establish cover crops in central Washington.

Biosolids are human waste recycled from sewage treatment that is used in agriculture. This organic matter is broken down by bacteria and composted before it is applied to soil, said Deirdre Griffin LaHue, assistant professor of soil quality and sustainable soil management at WSU. Griffin LaHue is based in Mount Vernon with the Northwestern Washington Research & Extension Center.

The project aims to determine how biosolids affect soil and how long this process takes after being applied to crops in central Washington, a non-irrigated area with little precipitation, Griffin LaHue said.

“Soil health is a very hot topic and people are realizing how important the soil is for regulating environmental processes,” she said. “Not only is the soil important for our food supply, but also for keeping a good, clean environment. There are multiple benefits both for the farmers and the public by looking at practices that improve soil health.”

Areas with low amounts of rainfall rely on cover crops for soil conservation during the offseason. Cover crops are planted alongside cash crops during the season to combat the dry environment, and biosolids could help establish these cover crops, Griffin LaHue said.

The organic matter helps regulate water, air quality and other environmental processes. Biosolids can also improve crop quality and increase yield per acre, she said.

“There are some challenges for growing crops [in central Washington],” Griffin LaHue said. “It is an important agricultural area, so the goal is to show the benefits we have seen in other systems and trials, and if there’s a benefit with this cover crop graze trial as well.”

Researchers will study how biosolids influence soil health properties through the comparison of cover crop and un-grazed plots with three different treatments: biosolids, synthetic fertilizers and unfertilized treatments. Researchers then measure the differences in soil health indicators, said Madeline Desjardins, doctoral student in the Department of Crop and Soil Sciences at WSU and NWREC.

“The way we conduct research is we take soil samples in the spring and process those samples,” she said. “We take different depth increments to look at [the] different health parameters. Then we process those and either conduct in-house lab analyses on them or send them out.”

Researchers will analyze physical, chemical and organic matter properties of the soil after the different treatments.

Physical properties include water storage and level of compaction, and chemical properties include the number of nutrients and carbon in the soil. Biological properties include the microbiome, or groups of bacteria, in the soil, Griffin LaHue said.

A soil test is conducted before biosolids are applied to the area to prevent an overload of nitrogen and other elements. Biosolids are then placed into a manure or compost spreader and applied to the soil, she said.

“Too much nitrogen in the soil can cause issues with water quality or loss of that nitrogen from the soil,” Griffin LaHue said. “In areas where there is a lot of rain, you can get leaching of nitrogen, and it will go into groundwater or surface water.”

Griffin LaHue and Desjardins collaborate with the King County Department of Natural Resources, which produces and provides the research team with biosolids, Griffin LaHue said.

The project began last year and is in the beginning stage. The team has had only one full season and has not produced major results. The project does not have an explicit end date, but Griffin LaHue said she hopes the project is funded for the next five or ten years.

“The other long-term biosolids experiment we have is about 25 years old,” she said. “It is extremely valuable to have those long-term plots or experiments because we can continue to ask and research questions.”

![“[The heat] really has an effect on how much we have available to meet orders every week.](https://dailyevergreen.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/DSC_0565-2-475x316.jpg)