Corals suffer as climate changes

Evolutionary biologist hopes to use new species to develop warm water-resistant coral

ADAM JACKSON | The Daily Evergreen

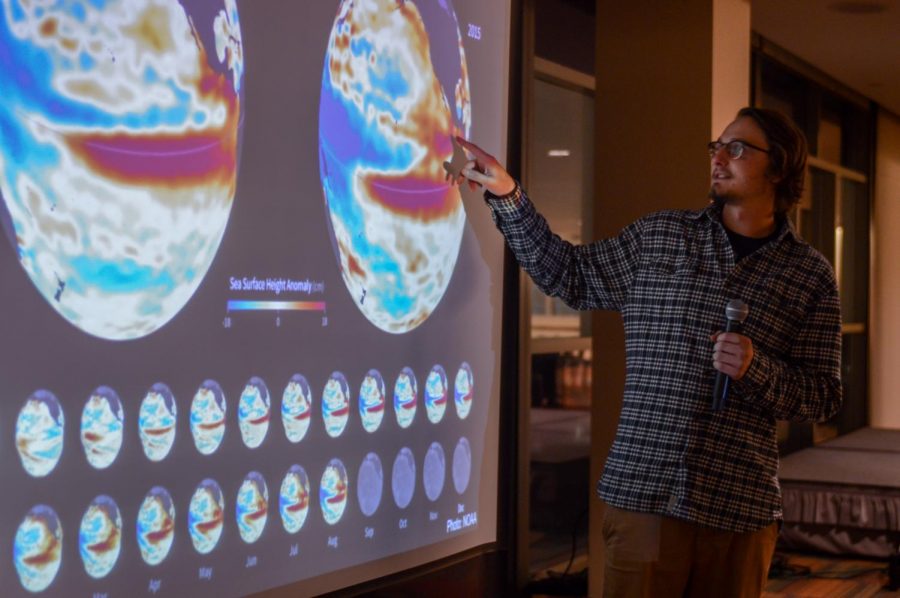

Environmental activist Zack Rago explains the damaging effects of the 2015 El Nino on the Great Barrier Reef. Increases in only a few degrees Celsius can result in coral death.

April 19, 2018

Thriving and vibrantly colored coral reefs, home to all kinds of sea life, have long blanketed the ocean floor. But now, much of it lies dull and lifeless.

Zack Rago is an underwater camera technician for View Into The Blue, the first company to capture underwater time lapse footage, which can be seen on the Netflix original documentary “Chasing Coral.” He described his experience in a keynote speech hosted by the Environmental Sustainability Alliance at the CUB Junior Ballroom on Wednesday.

“My job is to literally watch an ecosystem that I love die,” Rago said.

His passion for marine life and coral started when Rago spent his summers in Hawaii, following his dad on educational projects. As a child, he would catch creatures and explore the ocean, later becoming an avid diver.

“Chasing Coral,” which he is featured in, reveals a world that is quickly declining. It documents one of the largest coral bleaching events ever to occur, due to rising ocean temperatures.

The idea of the documentary was to capture the bleaching event using cameras that needed no human interaction. Due to unforeseen events, the cameras didn’t work and the team decided to take pictures manually.

“Failure and science are one and the same,” Rago said. “The best questions in life come from failure.”

They dove for 55 days straight, taking photos of the same reef for five hours every day to capture the bleaching. Rago said watching the Great Barrier Reef ecosystem wither away in front of him was one of the hardest things he has ever done.

“I felt crushed and hopeless watching something I really enjoy perish,” Rago said.

Last November, Rago and his colleague discovered two new species of coral in the northern region of the Great Barrier Reef off the coast of Australia. In this region, 95 percent of the coral died, except in one small location.

“This coral reef should not exist,” Rago said. “It should not be that healthy and it should not have been able to survive through 2016 and 2017.”

Something about these corals allowed them to withstand bleaching in a region they should have died in, and Rago hopes to unlock that potential to save other reefs. This new reef is so rare that the GPS coordinates are a secret.

The reef is also highly productive, and has micro reefs growing on top of it. The reef itself is over 900 years old, Rago said.

“It has been around for so long that there is a functional ecosystem living on top of it,” he said. “That is rad.”

Though coral reefs around the world continue to die at an increasing rate, Rago said there is hope. In another region where 99 percent of coral died, a single coral plant survived, meaning there is something genetically different about that one plant that could help reefs around the world survive.

At a certain time during the full moon in November, each individual coral plant releases eggs and sperm into the water, acting as seed banks rejuvenating the next generation of coral.

Marine biologists hope they can create a new genotype of coral that is able to survive warmer ocean temperatures. The idea is to take corals that survive in decimated areas and create offspring with their genetic material.

“We call this assisted evolution,” Rago said. “We’re giving them a helping hand to hopefully cope with the future they are going to see.”

Rago said he hopes that by combining science and art through projects like “Chasing Coral,” the public perception of environmental issues like coral reef death will change.

“Scientists don’t get involved to crunch numbers — they get involved because they have a deep care for their subjects,” Rago said. “They love it enough to continue exploring it for the rest of their careers, which is what science is about.”

This story has been updated to include that the Environmental Sustainability Alliance hosted this event