WSU technology protects crops from frost

Researchers form company to manufacture, commercialize formula

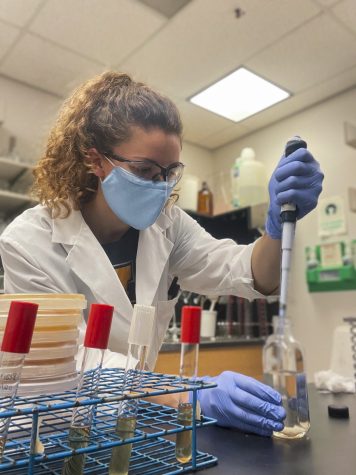

A WSU researcher sprays tree fruit with cellulose nanocrystal treatment that protects the fruit from frost damage. Cellulose is a component of plant walls that adds rigidity.

February 18, 2021

Every year, farmers around the world are plagued by crop loss due to cold temperatures and frost, no matter what fruits, vegetables or grains they produce.

A WSU research team developed a sustainable formula that acts as a protective barrier from the cold, an innovation that could revolutionize less reliable farming techniques, said Matt Whiting, WSU Department of Horticulture professor.

The formula uses cellulose nanocrystals that are made of chemical compounds. Cellulose, a component of plant cell walls, is broken down into crystals of microscopic size, Whiting said. The material is approved by the Environmental Protection Agency.

CNC can be found in all trees and vines the team tests the formula on, he said.

Xiao Zhang, WSU associate professor and Whiting’s colleague, worked on chemical engineering for several years. About four years ago, Zhang showed Whiting CNC. Zhang described how when sprayed as a film, it creates an insulative layer.

Whiting said he instantly thought this substance could work to protect crops from frost damage. Together, the researchers first sprayed CNC on wine grapes from Prosser, Washington, then put the grapes in a programmable freezer and analyzed the temperatures the plants were killed at.

Buds sprayed with the formula withstood cooler temperatures than the ones not sprayed, he said.

From there, the experiments continued with tree fruit, like sweet cherries, apples and pears. The researchers increased the size of the CNC sprayers and increased the numbers of plants they experimented on throughout the years, Whiting said.

“Every time that we’ve scaled up, it’s worked,” he said.

The team modified the CNC formula by adding raw plant materials, Whiting said.

“There really has been no innovations in how to reduce cold damage,” he said. “Growers have been using the same techniques to try to prevent frost and cold damage as their grandfathers have.”

Washington farmers typically use wind machines to prevent frost damage, Whiting said.

Thousands of wind towers surround Yakima Valley to displace cold air that settles in the valley and replace it with warmer air, Whiting said. This raises the air temperature by a few degrees.

After studying CNC for years, Whiting said he has not found any negative impacts from using it as a protective film largely because it is composed of natural resources.

Brent Arnoldussen, fourth-year horticulture doctoral student, said he grew up in Wisconsin where tree fruit is not part of the horticultural industry because of the state’s cool climate.

He became involved in the project three years ago when he witnessed crop loss firsthand in his home state. Arnoldussen said he wanted to help farmers protect their livelihood.

Arnoldussen said he helped build the sprayers for the project and worked with growers to test the formula on plants.

Because the formula was developed in a university-owned lab, the findings are owned by WSU, Whiting said. Whiting and Zhang formed a startup company called Pomona Technologies to negotiate a license for intellectual property from the university.

If they receive the license, the researchers would be allowed to manufacture and sell the spray to farmers through the company, he said. A commercial product could be seen in 2022.

“We decided that we would be better off doing this ourselves,” Whiting said. “We’re excited about the possibilities and we feel like we’ve got a technology that can save crops.”

In addition, the research team submitted funding requests to further study blueberries, blackberries and cranberries using the formula, he said.

“There’s no reason to expect that [the spray] wouldn’t work just because of the mode of action. It’s not specific to the crop,” Whiting said.