Make a buzz to save the bees

WSU Bee Program critical to protecting Caucasian honey bee from imbreeding, parasitic mites that infest, infect hives

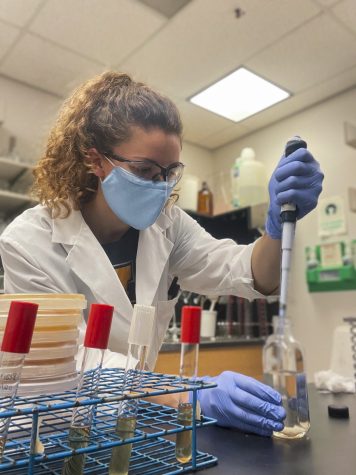

WSU Bee Program Researcher Jennifer Han, left, and graduate student Adam Ware, right, check honey bee hives treated with fungus for mite populations in collaboration with a company called Fungi Perfecti.

November 4, 2021

WSU Bee Program researchers are making a buzz to ensure the survival of the honey bees.

Honey bees without a honey

Genetic diversity is a big problem for honey bees, said Steve Sheppard, honey bee biology professor and WSU Bee Program researcher.

“No honey bees are native to North America,” Sheppard said.

To refresh the gene pool, bees must be imported. Unfortunately, European honey bee importation was banned in 1922 to prevent introducing tracheal mites into the U.S., Sheppard said.

Instead of importing live bees, bee semen was frozen through cryopreservation and imported to the U.S. to reverse genetic bottlenecks, which occur when there is too much inbreeding. WSU has a permit to import preserved European honey bee semen, he said. The imported semen diversifies honey bee genetics, increasing resistance to parasites and disease while improving overall honey bee health.

Bee Program researchers inseminate queen bees with imported semen and identify beneficial traits, which allow them to produce queen bees with the best available genes, he said.

“We’ve selected bees for more than 20 years here at WSU,” Sheppard said.

WSU-bred queen honey bees are available to commercial queen bee producers across the country. WSU is the only selective breeding program in the country collecting and using cryogenically-preserved semen, Sheppard said.

Pollinating the population

The Bee Program is combining its breeding expertise with extensive research to understand why honey bees are perishing.

“Honey bees and other pollinators have been in decline for decades now,” Bee Program researcher Nick Naeger said.

Habitat loss, pesticides and high rates of disease are all contributing to the collapse of pollinator populations, Naeger said. However, the main culprit in declining honey bee populations is the aptly named Varroa destructor, a parasitic mite.

“Varroa is currently the top health issue for honey bees,” he said. “There’s nothing else more likely to kill your colonies at this point in time.”

Varroa mites are vicious parasites. They chew holes through host bees’ protective exoskeletons, feeding on the festering wounds, spreading viruses and laying eggs on bee larvae, he said.

Forty-five percent of U.S. honey bee colonies died last year alone, according to the Bee Informed Partnership’s Loss & Management Survey.

“One-third of our diet is dependent on insect-pollinated crops, and honey bees are the major pollinator of modern agriculture,” Sheppard said.

No need to fear, mushrooms are here!

Another portion of the Bee Program focuses on using fungi to combat varroa mites and diseases.

“People had noticed honey bees foraging in cultivated mushroom beds, and this led us to think that bees were getting something nutritional or pharmaceutical from these mushrooms,” Naeger said.

The program is partnered with a mushroom remedy company called Fungi Perfecti, which supplies fungal extracts to feed bees, he said.

“Overall, we’ve seen very good positive effects when bees are fed these fungal extracts,” he said. “It seems to help them fight microbial diseases, and it may just be helping make them healthier overall — with better nutrition and a better-balanced immune system.”

Bee Program researcher Jennifer Han has also been working with fungi.

“We’ve been developing a fungal strain to be a better strain at killing varroa,” Han said.

Varroa mites were once controlled by toxic pesticides, which harmed bees and contaminated honey. But now the mites have developed resistance. Han said her Metarhizium fungus strain targets the mites specifically without the use of harsh chemicals.

Another possible solution to rid honey bees of varroa mites is overwintering honey bee hives in controlled atmospheric conditions, like an old apple storage facility, she said.

Honey bees go into a dormant state during the winter and stay in their hives until temperatures rise in spring. During the winter, varroa mite populations within the hive multiply dramatically.

“The interest is whether or not high carbon dioxide levels will result in increased mite mortality — so that you could put your bees in cold storage and also control the mites,” Sheppard said.

Making a bee-g difference

Last March, the new WSU Honey Bee and Pollinator Research, Extension, and Education Facility opened in Othello, Washington. But equipment was transferred to the facility only recently because of shutdowns caused by the pandemic.

The Bee Program is unique because it focuses on applying its research to benefit both commercial and small-scale beekeeping communities, Bee Program researcher Brandon Hopkins said.

“This program does very well to have a boots-on-the-ground approach,” Naeger said. “When beekeepers encounter a problem, they come to us.”

The Bee Program is crucial, especially when it comes to a subspecies that agriculture depends on: the Caucasian honey bee.

“Without the WSU Bee Program, there would be no Caucasian honey bees in the U.S.,” said Adam Ware, WSU graduate student working in the Bee Program.

Thanks to the busy bees of the Bee Program, honey bees have a chance.