Researchers address challenges in wine production

Study to focus both on positive and negative aspects of wine

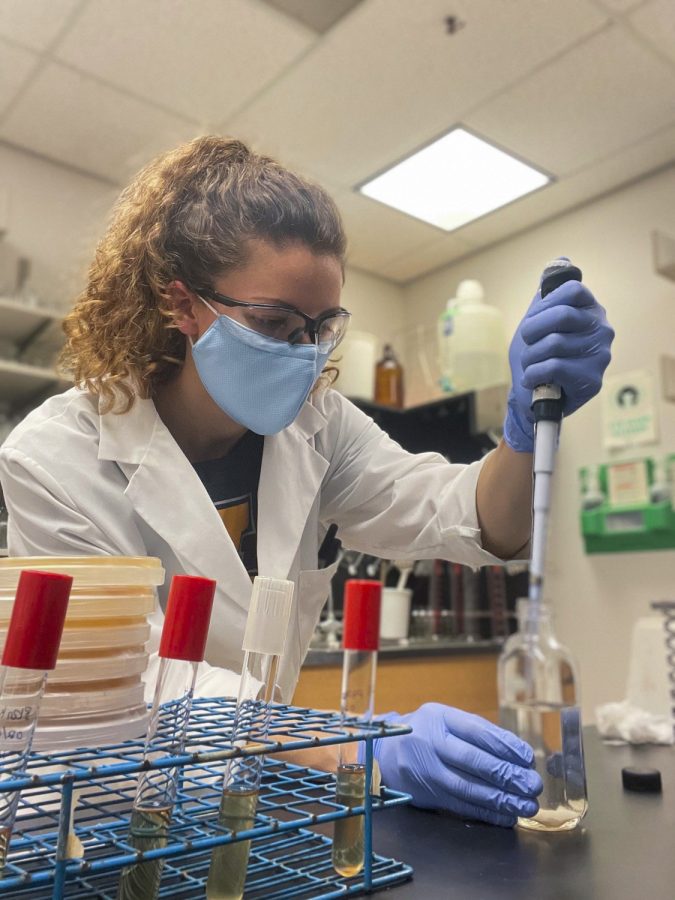

COURTESY OF HEATHER CARBON | FILE

Food science graduate student Heather Carbon collects a fermented sample of synthetic grape juice made from wild yeasts.

February 17, 2022

WSU researchers are studying the fermentation process of wines and ciders to adapt to sudden climate changes affecting grapes.

Fermentation is the process of fermented yeast taking sugar and metabolizing it to create ethanol. The more sugars in the Grape Must, the more ethanol produced, said Charles Edwards, food scientist and professor at WSU.

Grape Must is the mashed grapes and grape juice before adding in the fermented yeast, Heather Carbon, graduate research assistant for the School of Food Science, said.

The study focuses on both the positive and negative aspects of wine — the positive being focused on enhancing the quality of wine, whereas the negative deals with spoilage issues, Edwards said.

However, human pathogens cannot grow in wine, so it will be safe to drink, he said.

“For instance, red wine sometimes has a very funky smell, kind of like wet wool,” Edwards said. “That is due to a yeast that can be found during the aging process.”

Red wine is aged in oak barrels anywhere between 16 and 18 months. The yeast thrives in that environment, so researchers are focusing on that particular yeast and what winemakers can do to limit the risk of their wines having it, he said.

“Right now, we are focusing on a different yeast that grows on the grapes,” Edwards said.

Grapes are loaded with yeast; they are all over the grape itself. There are a couple different species of yeast that can have a positive effect on wines, he said.

Winemakers are harvesting grapes later in the season and the sugar content is higher than what they are used to, Edwards said.

One of the big questions winemakers face is “when are the grapes actually ready?” *double quotes -TD Some winemakers are trying to change the sensory profile of their wines. By waiting, that can be changed, he said.

“The weather has taken a toll on the grapes. The sudden heat waves cause grapes to ripen quicker,” Edwards said. “With the heat, you have to water more, and winemakers have to watch for that, as well as vine vigor.”

The Palouse used to get a cold snap every seven years, preceded by a warm trend. This triggered the grapes to grow their blooms, but then the cold would hit and kill the top parts of the vine, he said.

Unfortunately, all of this increases the sugars, Edwards said.

“There comes a point where the yeast do not like to ferment up 15.5% ethanol. It gets toxic for them,” he said.

Because of this, wine makers are being taxed higher. Consumers do not like a lot of ethanol in wine, so the question is, “how do you reduce the amount of ethanol?” Edwards said.

One way is diluting the solution with water. By adding water, the volume is increased while the sugar content is diluted, he said.

There are alternative ways, and that is what we are working on, Edwards said.

Researchers are studying a variety of yeasts native to Washington to benefit the wine industry, Carbon said.

There is a particular yeast that can chew through the sugar and does not produce a lot of ethanol, Edwards said.

“We are working with non-Saccharomyces yeasts, which are native yeasts found on grapes, and the two species I am working with are Metschnikowia pulcherrima and Meyerozyma guilliermondii,” Carbon said.

When added to the Grape Must, the yeast reduces the sugar naturally through their metabolism after a few days. By the time the fermented yeast is added, the sugar content is already low, he said.

“We are providing winemakers a different tool for their toolbox,” Edwards said.

With this technique, researchers are helping winemakers cut back on ethanol, and giving them a positive way to improve the sensory aspect of their wines, he said.

“We are still in the phase of trying to optimize as to what conditions are best for encouraging these yeasts, but we are getting closer,” Edwards said.