Grant to help county FLOURISH

FLOURISH project is farmer-led, aims to minimize crop tillage, add plant diversity in fields

The Palouse Conservation District’s grant will allow landowners to apply for assistance in maintaining wildfire resiliency.

December 2, 2021

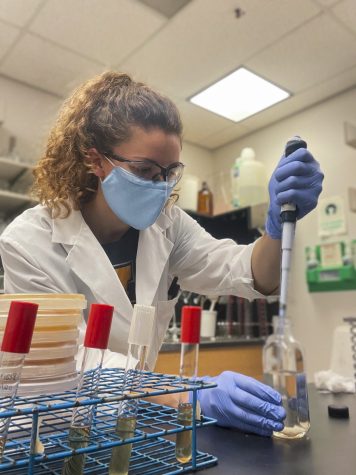

The Palouse Conservation District in Pullman received a five-year $2 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to support studies observing climate-friendly agricultural practices and soil health.

The Inland Northwest Farmers Leading Our United Revolution In Soil Health (FLOURISH) project is supported by the On-Farm Conservation Innovation Trials program, said Tami Stubbs, conservation coordinator for the Palouse Conservation District.

Each year, the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service opens up applications for Conservation Innovation Grants from a nationwide pool of money. The Palouse Conservation District competed with conservation districts all over the country to receive this grant, Stubbs said.

Conservation districts are local agencies that aim to conserve, protect or enhance natural resources, she said.

There are conservation districts in almost every county across the country. The Palouse Conservation District is one of four conservation districts in Whitman County, said Ryan Boylan, Palouse Conservation District research and monitoring coordinator.

As the lead of the FLOURISH project, the Palouse Conservation District will partner with farmers from Eastern Washington, Northern Idaho and eastern and north-central Oregon to study and adopt management practices to build soil health, Stubbs said.

“It’s important to emphasize that the work is farmer-led,” she said. “Growers will be doing the work on their fields. They will be providing input on the design of the study and then the work is conducted [in] their fields.”

One management practice is minimizing crop tilling. The Palouse region has a long history of soil erosion. It was estimated that 30 tons of soil were lost for every bushel of wheat produced prior to 1970, Boylan said.

To help minimize tillage, there are two proposed solutions: cover cropping and leaving crop residue.

Cover cropping is a practice of growing crops that are not cash crops, which are crops harvested for selling, Stubbs said.

In the drier areas of the Palouse, a fallow year is required after a harvest. The land sits idle where weeds are controlled either by herbicides or tilling. Having a cover crop during that period will protect the soil from erosion and promote soil health, she said.

Protecting soil health could also mean leaving crop residue in the soil following a harvest, she said.

Minimizing tillage and leaving more crop residue on the soil surface helps reduce erosion. The practice reduces impacts of rain on the soil, keeps soil in place during wind erosion and keeps roots in the soil to hold it together, Boylan said.

“We want to try and keep a living root in the ground as much of the year as we can,” Stubbs said.

This management practice can also benefit the climate.

“There’s some evidence — and still work to be done — that minimum tillage … helps hold carbon within the soil itself,” Boylan said.

By minimizing tillage, a farmer is also reducing the number of passes they do over their fields. This means there are fewer greenhouse gases emitting from equipment, he said.

Cover cropping will also help add plant diversity in the fields — this is one of the goals for the FLOURISH project. In the Palouse region, there are three major crop types that are rotated, Boylan said.

“But by introducing a cover crop, you’re introducing different diversity that helps soil microbiology, which then leads to improved soil health, hopefully, in the long term,” he said.

Lastly, cover cropping reduces the usage of herbicides because they suppress weed growth, Stubbs wrote in an e-mail.

One more consideration farmers will be making is whether to integrate livestock, she said.

There are potential benefits of integrating livestock into farms because their waste is a source of crop nutrients. Livestock can also eat cover crops down to the ground, Boylan said.

The FLOURISH project will allow farmers to integrate these different factors into their harvest. The Palouse Conservation District will assess the impacts of their practices on soil health. As a control, the fields in the study will be compared to a “business usual” field of the same size, he said.

“So they’ll have, say, a 30-acre field of cover crops or cover crops integrated with livestock,” Boylan said. “We’ll compare information from that field to a 30-acre field that is directly seeded with cash crops.”

The farmers participating in the study already minimize tilling. However, they want to improve soil health even further, Stubbs said.