Sobriety not required to reduce alcohol dependency

Traditional treatment system fails many people, including study participants, researcher says

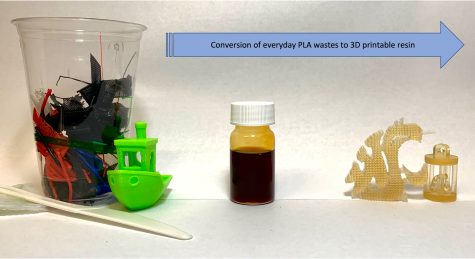

The Dutch Shisler Sobering Center is where the researchers worked with participants and educated them with methods to stay safer even if they kept drinking.

April 1, 2021

People experiencing alcohol use disorder can reduce alcohol dependency without giving up alcohol, WSU researchers found.

Alcohol use disorder is a diagnosis that consists of different levels of alcohol-related harm, like liver failure, and clinical distress as an effect of that harm, said Susan Collins, lead author and WSU psychologist.

A study placed 405 participants randomly into four groups to analyze which strategies, medication or harm reduction counseling, reduce the most alcohol-related harm, said Richard Ries, professor of psychiatry at the University of Washington Medical School.

The first group received anti-craving medication and harm reduction alcohol counseling. The second group had a combination of a placebo medication and counseling. The third group received only counseling, Ries said. The fourth group functioned as a control with no medication or counseling.

The combination of medication and harm reduction counseling provided the best results to reduce alcohol-related harm, he said.

The anti-craving medication the researchers used was naltrexone, which blocks the reward pathway. When the participants use the medication, they reach a certain level of intoxication, and the individual feels satisfied while also less likely to experience harm from excessive drinking, Collins said.

The researchers did not tell the participants to change their drinking habits, Collins said. The participants in the counseling and medication group reduced the number of drinks consumed on their heaviest drinking day by 59 percent.

The same group had 29 percent of the participants drink for fewer days over a month as well as a 43 percent reduction in alcohol-related harm, she said.

The 405 study participants were homeless individuals in Seattle, Washington, Collins said.

The participants had gone through traditional abstinence-oriented alcohol treatment several times, but it did not work, Ries said.

They did not fail alcohol treatment. The treatment system is failing the people, Collins said.

Homeless individuals experiencing alcohol dependence visit hospital emergency rooms frequently because of intensive medical sickness and bodily harm from alcohol, Ries said. Stabilizing their alcohol use and reducing alcohol-related harm would benefit the individual.

“People who are experiencing severe alcohol use disorder often have a lot of medical complications,” Collins said.

The participants had not yet experienced the alcohol-reducing-related approaches used in this research, Ries said.

Improving the effectiveness of treatment includes educating people with methods to stay safer and healthier, even if they continue to drink, Collins said. It is also important for people to consider the goals they have for themselves instead of providing a high barrier of commitment to stay sober.

The counseling included a questioning period that asked participants about alcohol-related harm they had experienced in the past 30 days, she said.

One step of the counseling determined what goals people had for their alcohol use or, more generally, their quality of life, Collins said. A quarter of the participants focused on achieving basic needs that had nothing to do with alcohol use. Roughly six percent of participants wanted to become sober.

Another quarter of the participants wanted to reduce alcohol use and alcohol-related harm. The other participants had goals to reconnect with their family to improve their quality of life and health, she said.

The final part of counseling provided safer drinking strategies to the participants, so they have more knowledge to protect themselves from alcohol-related harm, Collins said.

“What we are doing today to ensure that we’re supporting patients’ autonomy, that we’re advocating for folks who are marginalized in the system, and helping them to advocate for themselves,” she said.