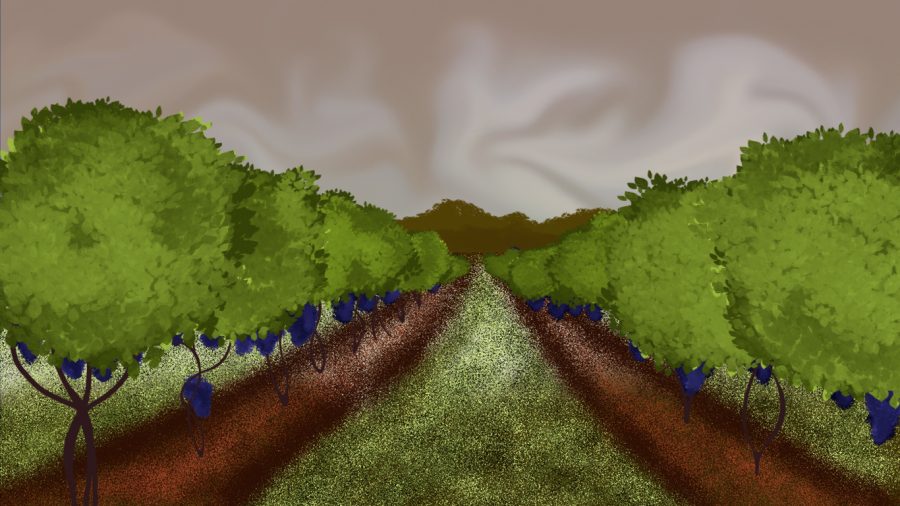

Save the grapes, fight the smoke

WSU researcher combats damaging effects of smoke exposure

The grapes are kept in six portable hoop houses, which contain a set of frames and shade cloth that cover a variety of grapes.

September 2, 2021

Following the destruction of the wildfires over the past few years, researcher Tom Collins has developed solutions to fight harmful effects from smoke exposure on wine grapes.

Collins, WSU Viticulture and Enology Program lead researcher and assistant professor, said he is performing trials on six houses of grapes at Roza Research Farm in Prosser, Washington.

The grapes are kept in six portable hoop houses, which ensure a controlled environment. Each house contains a set of frames and shade cloth that cover a variety of grapes. Three houses are smoke hazards and the other three are controls. Particle counters are used to measure the smoke density allowed in the houses.

“This way we have a little more control over what happens during these exposures than what would happen with natural exposure,” Collins said.

The grapes are exposed to smoke for a 36-hour period, then samples are taken and analyzed. He said he is measuring how the grapes are affected by factors like proximity and duration of smoke exposure.

“What we are trying to understand is how the various factors related to smoke exposure relate to one another and how they will interact to potentially create a problem,” he said. “We are still working to see how these [various factors] interact.”

Vineyards in closer proximity to the fires are generally more at risk than those with prolonged exposure further away, Collins said. However, the circumstances may vary on a case-by-case basis.

Collins and his research team are currently on their fourth exposure trial of this year; the first began in July after the fruit was set. The trials take place throughout the growing and harvest season and each occurs in two-week intervals.

This is the third year of these types of trials. Collins said it is important to continue the trials each year to see if results will vary from one season to the next.

One of the preventative measures Collins is testing involves protective barrier sprays. The sprays are applied to a section of grapes during the trials in the hoop houses, then are collected and analyzed after exposure.

Collins said the intent of the spray is to minimize the effects of smoke exposure on berries. Various sprays have been applied in different blocks and will be monitored over the next year to see if they reduce smoke uptake.

“The idea is that either you prevent the smoke from getting to grape berry surfaces, or you have some material that absorbs these compounds before they can be applied to the plant,” Collins said.

Melissa Hansen, Washington State Wine Commission research program director, said high-tech air sensors are not commercially available as they are still prototypes but may act as a preventative measure by helping growers track smoke quality in their area.

Collins said he is also working on several treatment measures because harvested smoke-damaged grapes can impact the aroma of wine during the fermentation process.

There are certain compounds, such as terpenes, that are important in the process of creating wine and giving certain aromas or tastes, but when grapes are exposed to smoke, important characteristics and compounds can be stripped away, he said.

Some research is focusing on selective ways to remove compounds from the smoke that are present after wine is made, Collins said. This is part of a process called reverse osmosis.

“As harvest is coming around, our focus will shift more to things we can do in the winery to have an impact on the final outcome,” he said.

Collins said his research is evolving and will continue, building off of preliminary results. However, he said it is important to remember that just because a region experiences smoke, it does not mean that the grapes have been negatively impacted.

“Ultimately, we would like to be able to help people understand what the risks are associated with any particular exposure, so that they can make better decisions about how to handle their fruit,” Collins said.